Hamas’s October 7 atrocities were innovative—for instance, the attackers livestreamed their actions with Go-Pro cameras—but they also fit an old pattern known to those familiar with the region’s history. Hamas said it was defending Jerusalem’s al-Aqsa Mosque, and named its attack “al-Aqsa Flood.” In the 1929 Hebron massacre in British Mandate Palestine, the Arab rioters, who killed nearly 70 Jews, likewise screamed that they were defending al-Aqsa, which brings to mind Faulkner’s aphorism, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

This parallel is not mere coincidence, and shows something besides the impressive consistency of anti-Zionist propaganda over the past century. Linking the two episodes is the killers’ sense that massacres of civilians are politically beneficial. If one fails to acknowledge that political calculation, it is impossible to understand either the terrorists’ motivations or how best to counteract them.

In 1929, British officials responded to the bloodbath with pro-Arab policy initiatives, much as present-day governments in Britain and elsewhere have responded to the war launched by Hamas on October 7, 2023 by recognizing a Palestinian state. History shows that those initiatives in 1929 were a huge mistake. They produced ugly, long-lasting effects on Palestinian Arab political culture. Indeed, the 2023 attack can reasonably be seen as a result—a distant but direct reverberation—of the errors those officials made by rushing, in effect, to reward savagery.

In 1929, as in 2023, the Arab attack took the form of torture, rape, murder, arson, and pillage. Raymond Cafferata, the British police superintendent in Hebron, later testified to an investigating commission, “I did all in my power to protect the two Jews by surrounding them with my mounted men but the mob surged round and stoned them to death within two minutes.” He continued, “Crowds who had been watching the attack and murder of the two Jews from the road and surroundings then started to attack each Jewish house. They were armed with crowbars, sledgehammers, swords, and knives.” Among his many appalling recollections was that he “saw an Arab in the act of cutting off a child’s head with a sword; he had already hit him and was having another cut but on seeing me he tried to aim the stroke at me but missed” and “I shot him.” Cafferata also told the commission he stopped a rape: there was “a Jewish woman smothered in blood with a man I recognised as a Police constable named Issa Sherrif from Jaffa in [civilian clothes]. He was standing over the woman with a dagger in his hand. He saw me and bolted into a room close by and tried to shut me out—shouting (in Arabic), ‘Your Honour, I am a Policeman.’ (This man subsequently died.) I got into the room and shot him.”

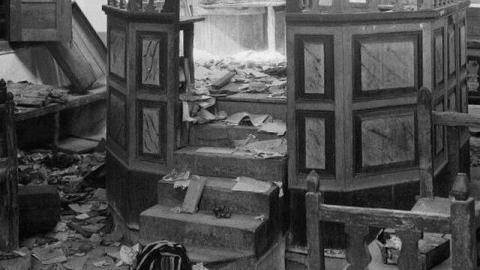

The attackers wrecked a synagogue and a hospital, incinerated homes, and looted shops. They succeeded in obliterating the Jewish community that had lived in and around Hebron for many centuries—according to the Bible, from the time when Abraham and Sarah were entombed there in a cave that the Hebrew patriarch had bought from its Hittite landowner for 400 silver shekels. Arab policemen generally failed in their duty; a number joined the mob. While some courageous Arabs protected their Jewish neighbors, other Jews were hacked to death by people they knew by name and had long lived beside. Anti-Jewish mayhem spread to towns and villages throughout Palestine.

British officials condemned the rioters in 1929 for pitiless murder, and then tried to mollify them. They failed. The consequences of their appeasement effort remain with us today.

When people get rewarded for acting brutally, the world becomes more jungle-like. Palestinian Arabs have been fighting Jews violently in the Holy Land for a little more than a hundred years. The strategy has hardly brought them success, but they have retained it, in part because anti-Jewish mayhem brings them political rewards from important foreign actors. This was true in the 1920s and remains so in 2026.

In light of the events of the past two years, the Hebron riots’ history warrants review.

In the late 1920s, Britain governed the Holy Land. The youthful Arab leader, Haj Amin al-Husseini, who served as Jerusalem’s mufti and the president of Palestine’s Supreme Muslim Council, used religious schools and mosques to promote the accusation that the Jews were plotting to destroy al-Aqsa. Although the accusation was false, it was widely believed in the Arab community.

In 1929, Husseini’s campaign of incitement helped bring about two weeks of anti-Jewish atrocities in multiple towns and villages, of which the Hebron massacre was the worst instance. In total, 183 Jews were killed and 339 wounded.

High Commissioner Sir John Chancellor, the British-appointed governor of Palestine, disapproved of Zionism, but was appalled. In his diary, he wrote, “I do not think history records many worse horrors in the last 200 years.” A long-serving imperial administrator, Chancellor took office in Jerusalem in 1928, after time in the British army and colonial service, including as governor of Mauritius and then of Southern Rhodesia. He had little experience with Jews, no expertise on Palestine, and scant exposure to the Middle East in general. He was handsome, but that was not enough to make him a popular figure in Jerusalem society, and his grumpy demeanor offset any advantage gained by his looks. Though he displayed neither broad intellectual interests nor personal warmth, he spoke impressively about policy and his opinions won respect.

Chancellor claimed to have brought no political preconceptions to Palestine, but quickly came to champion ideas hostile to the Jewish national cause. This aligned him with most of his subordinates in the Palestine government, but it put him at cross-purposes with Britain’s declared policy of support for the creation of a national home for the Jews in their ancient homeland. That policy, originally formulated in the 1917 Balfour Declaration, became a legal obligation when incorporated into the Palestine Mandate, a trust supervised by the League of Nations.

Though Arab leaders for years had insisted that they would never consent to large-scale Jewish immigration, never agree to a Jewish national home, and never join an administration rooted in the Balfour Declaration, and would prefer to fight to the death than to compromise on these positions, British officials generally disregarded these “nevers.” They simply assured themselves that the Arabs over time would moderate.

Then came the 1929 riots, which rocked the government. In Britain, they produced moral outrage. They also, however, energized anti-Zionist forces, who interpreted the inhumanity of the bloodletting as a sign of the vehemence of Arab grievances. High Commissioner Chancellor proved far more eager to accommodate than to punish those responsible. He favored radical policy changes to remedy Arab complaints against the Jews and pressed for these changes as necessary to prevent future riots.

Some British opponents of Zionism had long advised Arab leaders to keep the peace, on the assumption that disturbances would hurt the Arab cause. Throughout much of the 1920s, senior figures in the Arab establishment accepted the advice. The riots, however, gave rise to official British initiatives to placate the Arabs, which would permanently alter Arab attitudes toward the use of violence.

Thanks to the British pro-Arab initiatives that followed the 1929 disturbances, the threat of more riots became the mainspring of Palestinian Arab diplomacy. When the British formed a commission to investigate the riots, the once cautious Arab Executive—then the key Arab political organ in Palestine—began issuing threats: its president (an older cousin of the mufti) gave British officials a “warning” of “an armed Arab rising” if the investigating did not lead to cancellation of the Balfour Declaration. A Daily Express correspondent reported on September 2, 1929 that Mufti Husseini said, “Ultimate peace in Palestine and Arabia will never be made while Great Britain continues to pursue the policy of the Balfour declaration.” The mufti later described the 1929 riots as a “spontaneous and uncontrollable protest” against “unnatural and unjust Zionist aggression.” A British admiral sent London reports of Arabs saying that “next time they will make a more thorough job of it.” British intelligence noted that preparations were underway for a “general uprising, well armed and organized for action against the Jews” and that the Arabs would attack the Jews “by all means at their disposal, and at whatever cost.”

This intimidation campaign succeeded. Colonial Office experts proposed backing away from the Balfour Declaration. Typical was O.G.R. Williams of the Middle East Department, contemplating the best response “in the face of the increasing threats of violence on the part of the Arabs.” In an alarmed and alarming November 13, 1929 memorandum, Williams said Arab leaders were focused on what conclusions would be drawn by the investigating commission. If it fingered the Arabs and linked the violence to “preconcerted action,” he warned, then “Arab dissatisfaction” would produce an even worse “explosion.”

To head off that explosion, Williams said officials should ascertain “Arab grievances and apprehensions” and “allay them, so far as possible.” He recognized that there was danger in any “appearance of weakening,” yet the “risk of bloodshed” persuaded him that the high commissioner should reach out to Arab leaders to ease tensions.

At the same time, British intelligence was reporting that Palestinian Arab nationalists had created a “Boycott Committee” for “terrorist purposes with a view to the assassination of [Arab] persons considered to be acting against Arab nationalist interests.” The Committee was “formed with knowledge and consent of Supreme Moslem Council and Arab Executive who have subscribed to expense.” Its murder campaign, already underway, was organized “quite effectively,” and appeared to be “meeting with some success,” as evidenced by the drying up of Arab sources of information for the police.

High Commissioner Chancellor warned the Colonial Office that there would be hell to pay if the government did not adopt policies favorable to the Arabs. He cabled that he was “quite certain” that “there will be rebellion,” unless the Arabs “obtain some concessions, and the ambitions of the Zionists are curbed.” He added, “The Moslem population appear to be approaching a state of desperation on account of government’s failure to meet their wishes in any way.”

The high commissioner proposed actions to make the anti-Zionists happy. In London, officials debated the proposals and tried to ascertain what exactly the conflict in Palestine was about. Did the Arabs hate Jews or only Zionists? Was the hatred racial and religious, or was it political? Was it widespread or little more than a sentiment and tool of an elite who promoted it for selfish purposes among generally indifferent masses? Was the hatred appeasable?

British officials had long comforted themselves by downplaying the problem of Arab-Jewish enmity. They often denied that the hatred was widespread or so fundamental and intense as to be beyond pacification. The 1929 riots clarified the picture. Hebron’s strictly Orthodox Jewish community predated organized Zionism and was known in general to be unconnected to it. So the riots’ victims were not specifically Zionists, but simply Jews. The conflict was not mild and manageable, but murderous. It was not narrowly based, but popular. It was not focused on policy issues subject to rational debate and compromise, but rooted in religious and nationalistic passions that scorned accommodation.

The enormities of the rioters that had outraged even anti-Zionist British officials did not produce repudiations, apologies, or goodwill gestures from the Arab community, which evinced no collective shame. Rather, the community rallied to defend rioters facing official punishment, including convicted murderers. It raised money for Arabs who were hurt, but not for Jews. In meetings after the riots, its leaders spoke with officials aggressively and accusatorily, without restraint, let alone remorse. All of this pointed to bloody trouble ahead.

The British investigative commission, in its March 13, 1930 report, adopted High Commissioner Chancellor’s perspective. It described the riots as an Arab attack on Jews, yet, contrary to the evidence it collected, it cleared the top Arab leaders of accusations of intentionally fanning racial hatred and organizing the onslaught.

The key finding was that fear, not hatred, drove the Arabs to violence. According to the commission, the Arabs’ “fears for the future of their race in Palestine” were based on their belief that the Jews and British intended “to make them landless or to subordinate their interests as a people.” Jewish immigration aroused “apprehension in the Arab mind.” The Arab mayor of Nablus said the Zionists intended to “dispose of the Arabs” and “replace them with Jews.” The commission hammered the theme of the Jewish threat and the awful unease it caused among the Arabs.

Blame is a weapon of war and Zionism’s enemies scored an important success when the commission concluded that Jews who spoke provocatively—though they were non-violent—were mainly responsible for the anti-Jewish massacres. “Extreme statements” by Zionists caused the Arabs to see the Jewish immigrant as a “menace to their livelihood” and a “possible overlord.” In other words, it was the Jews’ fault that Arabs hated them so fiercely. If Zionists had been moderate and generous, the commission wrote, Arab opposition “might never have been fully roused or, if roused, might have been overcome.”

The British prime minister Ramsay MacDonald became “much perturbed,” according to a well-connected observer, because the report was “far too pro-Arab for the P.M.’s taste.” MacDonald, a principal founder of Britain’s Labor party, was an admired orator, gifted with a strong intellect and a kindly face decorated with an exuberant mustache. His politics were nimble, without ideological rigidity. Seven years prior, as leader of the Labor opposition, he had visited Palestine as a guest of the Labor Zionist movement. He supported the Jewish national movement in principle, but equivocated. Now he was caught in heavy cross-currents generated by disagreements about Palestine policy.

High Commissioner Chancellor, a determined wavemaker, pressed hard for his anti-Zionist policy proposals. He wanted the home government to gut the Balfour Declaration. His three immediate goals were restricting Jewish immigration, curtailing land sales to Jews, and creating a Legislative Council that would be popularly elected and therefore dominated by Arabs. It bears reiterating: he favored those measures in all events, but he was now able to argue, after the 1929 riots, that they were necessary to prevent future unrest.

The high commissioner’s position was adopted by his immediate superior, Lord Passfield, the colonial secretary. Passfield, a short, goateed, and bespectacled academic economist, had helped found the London School of Economics. He was a pacifist, though an admirer of Stalin, and a socialist, but by no means an admirer of the Zionist Labor party. Chaim Weizmann, the president of the Zionist Organization, saw the colonial secretary as “frightened,” a man who thought of himself as “patron saint of the Arabs,” whose role was “to protect the poor Arabs against the powerful Jews.”

In October 1930, Passfield issued a new pronouncement on Palestine, known to history as the Passfield White Paper. The document asserted that no policy in the Holy Land could succeed unless the Arabs as well as the Jews gave it “willing cooperation.” This sounded ordinary enough, even banal—a way of encouraging compromise and expressing faith that Arab-Jewish accord was achievable. But these words had the potential to undo the Balfour Declaration. They might just as logically be understood as encouraging Arab resistance, assuring rejectionists that they have the power to kill the Jewish national home by withholding their consent.

The crux of the White Paper was the set of pro-Arab measures championed by High Commissioner Chancellor. First was a promise to move “without further delay” to set up an Legislative Council with elected members. This, the document said, “should be of special benefit to the Arab section of the population.” Next, the White Paper expressed negative views of land purchases by Jews. Finally, the government would further limit Jewish immigration.

Throughout the government, officials felt uneasy that Arabs—and Jews too, for that matter—would see these pro-Arab measures as a nervous reaction to the riots. The White Paper’s supporters, however, argued that preventing future riots was crucial and the way to do that was to assuage Arab anxiety and resentment. The many British officials who accepted this argument thus risked the obvious danger of rewarding arson, pillage, and murder. The mere appearance of rewarding violence was likely to do the opposite of pacify. It might inflame. In fact, it might send a message to the discontented in Palestine that rioting is the surest path to political success.

The colonial administration was not composed of fools, and officials understood the risks of their preferred policies. They found a simple way to thread the needle: they took action that rewarded violence, but announced that they would never reward violence. Even as it altered policy to try to appease the rioters, the White Paper proclaimed that intimidation would never produce a policy change. To believe otherwise, the text said, was a “false hope,” as the government would “not be moved by any pressure or threats.” Few found this gambit persuasive.

Prominent members of Parliament lambasted the government for its pro-Arab turn. The White Paper was “almost universally regarded as a revocation” of the Palestine Mandate, the former prime minister David Lloyd George argued on November 17, 1930 in the House of Commons. “Not merely the Jews, but the Arabs take this view. The Jews regret; the Arabs rejoice.”

Toward Jewish activities, Lloyd George said, the White Paper “breathes distrust and even antagonism,” which was understandable only as the product of an “anti-Semitic” author. The White Paper complained of Jews who immigrated without permission, but it merely assumed they were Jews and said not a word about “the thousands of Arabs who have been doing the same thing.”

In this House of Commons debate, the Liberal Lloyd George received cross-party support. The Conservative Leopold Amery, a former colonial secretary, bolstered the case for upholding the Balfour Declaration. As a member of the War Cabinet secretariat in 1917, Amery had helped write the Declaration. He denied that it ignored the Arabs. The authors considered the Arabs’ position, Amery explained, but decided a Jewish national home was a matter of right and “that right should not be left to the discretion of conflicting Arab nationalism.”

Herbert Samuel also took to the floor. He was the Liberal party’s number-two parliamentarian and joined its leader, Lloyd George, in panning the White Paper. As Palestine’s first high commissioner (1920-1925), Samuel had had authority over all of Palestine, on both sides of the Jordan River. Believing the White Paper was wrong in claiming that Arab farmers lacked cultivable land, Samuel focused attention on eastern Palestine, known then as Transjordan. It had ample rich farmland, he said, available for Arabs from western Palestine who wanted or needed to relocate. He elaborated, “there is a constant movement to and fro” across the Jordan River and Transjordan urgently needs more population.

There were other problems with the White Paper, Samuel commented, including its promotion of the false idea that “any Jewish gain must be an Arab loss.” The worst flaw, however, was that it was changing policy “after massacre,” which could lead people in Palestine and elsewhere to think that “massacre is the road to obtain concessions.”

Among Palestinian Arab leaders, the riots and their aftermath caused the relative moderates to lose ground to the radicals—especially to Mufti Husseini. Husseini had been the loudest voice accusing the Jews of plotting to destroy al-Aqsa, fueling the country-wide anti-Jewish frenzy that brought about the riots and the astonishing subsequent British concessions.

Arab Executive members debated how to respond to the White Paper. Its pro-Arab qualities were noted, but detractors dominated the discussion. Rather than praise the decision to limit Jewish immigration, the Arab Executive ultimately issued a critical statement, knocking Britain for refusing to give the Arabs more power in the proposed Legislative Council. This was a sign that younger, more radical men—supporters of the mufti—were taking over leadership.

The high commissioner had crafted his pro-Arab agenda to induce the Arabs to moderate. But the Arab Executive’s response showed that it had the opposite effects, as could be expected of a policy based on appeasing violence. The radicals emerged stronger, and even the more moderate Arab leaders grew less inclined to cooperate with the government. If the White Paper had elicited the desired Arab response, perhaps the prime minister would have simply taken in stride the flak directed against the document from pro-Zionists in Parliament, as well as both Jews and Arabs in Palestine. It quickly grew apparent, however, that the change in policy was an unmitigated fiasco.

Husseini had ignited the violence that triggered the official British spasm of pro-Arab appeasement. He won credit among his own people for this, making the old guard, embodied in the Arab Executive, appear weak and overly cautious. He capitalized on his accomplishment to fulfill his long-term aspiration to political as well as religious preeminence. With its non-radical approach discredited, the Arab Executive soon ceased to function. The mufti, never a member of the Executive, emerged as the dominant force in his community and the leader of its wars against the Jews and the British. But he was not able to win those wars. Palestine’s Arabs to this day have not recovered from his failures—or even learned from them.

Four months after its publication, Prime Minister MacDonald effectively admitted that the White Paper was a bad mistake. He cancelled its main provisions in a February 13, 1931 letter he sent to the Zionist Organization. Lasting damage, however, was already done, for important Arab leaders had already become convinced that murderous riots made senior British officials eager to accommodate them.

As their internal memoranda showed, British officials knew what they had to do to accomplish Britain’s declared goals in Palestine—principally, to fulfil the Mandate by upholding the Balfour Declaration and to prevent a resurgence of Arab rioting. They needed to show strength of purpose, moral confidence, and willingness to use force to preserve law and order. Also, they needed to discourage bloody disorder rather than incentivize it.

Yet they failed.

They vacillated. They diluted their commitment to the Jewish national home. They deployed inadequate force and communicated reluctance to use it. They denounced brutal behavior but then rewarded it. They teetered, making themselves look irresolute, fearful, and vulnerable to pressure.

For Palestine’s Arabs, the lessons of British action in 1929 were that rioting pays and, when London is wobbly, the Arabs should be unyielding. British officials groused about Arab intransigence, but over time they gave in. The results militated against Britain’s official goals. The government was empowering Husseini and the Arab radicals. It was encouraging extremism, not moderation, let alone compromise with the Jews. It was ensuring future political violence. And the violence soon came.

Why did British leaders make so many poor decisions?

Part of the problem was that some officials, opposed to their country’s endorsement of Zionism, undermined rather than facilitated the Jewish national cause. Part was excessive faith in appeasement—the belief that Britain could make concessions that would satisfy the Arabs even while upholding Britain’s commitment to the Jews. This was a refusal to take seriously the declared determination by Arab leaders to oppose any kind of Jewish national home anywhere in Palestine.

Part of the problem was an unwillingness among British officials to use force to uphold their policy against enemies that were willing to resort to violence. Whether this hesitance reflected pragmatic calculations, pacifist principles, cowardice, or something else, it had unintended effects. It encouraged Arab anti-Zionists to use violent threats, riots, and terrorism to oppose the Jews.

The parallels to the current war in Gaza are obvious. Under the leadership of Yahya Sinwar, Hamas in Gaza designed a catastrophe in the form of a one-two punch. First, it launched the savage October 7 attack. Then, having constructed its tunnel system for terrorist operations, it ensured that Israeli self-defense would harm civilians and cause gross destruction of Gaza’s infrastructure. When the resulting condemnations of the IDF and calls for Palestinian statehood came, Hamas leaders could congratulate themselves. Even now, they celebrate their strategy, not despite the human suffering it causes, but because the suffering has so amply advanced their cause.

People around the world did express horror at the murders, rapes, mutilations, and kidnappings of ordinary men, women, and children by Hamas on October 7. Yet very little time passed before many of these same people, like High Commissioner Chancellor in 1929, argued that the key to preventing future terrorism of this kind is to placate the Zionists’ enemies—for example, by recognizing Palestine as a state, endorsing untrue reports of famine in Gaza, accusing Israel falsely of “genocide,” and otherwise delegitimating its actions to defend itself.

As in the aftermath of the 1929 riots, rewards for savagery will increase, not decrease, the likelihood of future terrorist violence. The responses of Western heads of state, journalists, professors, and human-rights institutions incentivize violence against ordinary Jews, while capitalizing on the misery of ordinary Palestinians. Intentionally or not, this lays a foundation for another century of self-defeating Arab anti-Zionist belligerence.

Such violence has never succeeded in blocking Israel’s progress. The rewards can be expected, however, to empower the more hateful and oppressive elements in Palestinian Arab politics, making peace with Israel harder to achieve. Ordinary Palestinians will suffer as a result of the wrongheadedness of their ostensible supporters, as they have for more than a century.

The above is adapted from the author’s book-in-progress on the pre-1948 history of the Jewish-Arab conflict in Palestine.