President Donald Trump’s offer to help North Korea combat the coronavirus pandemic is the right thing to do, but little is likely to come of the gesture. It is difficult to visualize Kim Jong-un grasping this opportunity after squandering so many these past two years.

Indeed, will Korea ever realize peace? Many Americans understandably chafe at the thought of lost lives and treasure in their seemingly endless wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Of course, these losses are dwarfed by the losses incurred during the Korean War and the subsequent years of stalemate. The Korean Peninsula is a stark reminder that the cessation of hostilities is no guarantor of peace.

Shortly after North Korea invaded the South in June 1950, the United States embraced, in the words of Max Hastings, “the least expected of wars, in the least predicted of places, under the most unfavorable possible military conditions.”1 The war pitted a reeling South Korea and hastily-assembled U.S.-led coalition that included troops from 15 other like-minded states against the Soviet and Chinese-backed North Korean military. As William Stueck observed, "The Korean War is an imperfect label since it reflects only the territorial boundaries, not the international dimensions, of the conflict."2 The war brought the world dangerously close to all-out conflict between the U.S.-led and Soviet-led blocs.

Fortunately, a direct and all-out major-power war was averted. However, T.R. Fehrenbach noted, “The great test placed upon the United States was not whether it had the power to devastate the Soviet Union—this it had—but whether the American leadership had the will to continue to fight for an orderly world rather than to succumb to hysteric violence.”3

When an armistice ended the fighting inconclusively on July 27, 1953, the Korean people absorbed the full anguish of a divided and still heavily armed peninsula. Neither order nor true peace had been achieved.

Since 1953, the peninsula has experienced both the lows of potential renewed open conflict and the highs of possible breakthroughs to peace. Pyongyang’s lethal provocations in the late 1960s, including the January 1968 commando raid on the Blue House and seizure of USS Pueblo in international waters, punctuated a period often dubbed “the Second Korean War.” Before the first nuclear crisis was averted by diplomacy in 1994, the United States was seriously contemplating a surgical strike on North Korea’s Yongbyon research complex. In 2017, “fire and fury” and a possible “bloody nose” preventive strike were discussed as part of the “maximum pressure” escalatory response to Kim Jong-un’s accelerated nuclear and long-range missile tests.

Yet before and after every low point on the peninsula, there were analogous high points, including ice-breaking inter-Korean agreements at the beginning of the 1990s, followed by Sunshine and Sunshine 2.0 North-South engagement policies, six-party talks, and bilateral summit meetings.

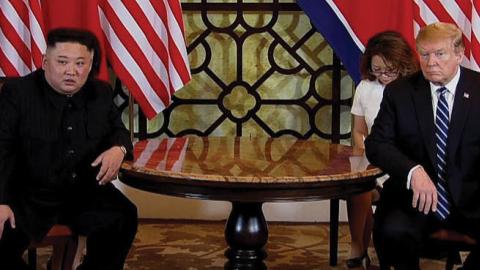

The year 2018 saw a record number of leaders' meetings over North Korea. Yet the prospect of peace on the Korean Peninsula appears as remote as ever. It's been only about two years, but the euphoria of President Moon Jae-in and Kim Jong-un's first romp at Panmunjom and the historic meeting between President Trump and Chairman Kim in Singapore—is a fading memory.

Unless the coronavirus crisis revives the spirit of Singapore, the peninsula is likely to continue its slow reversion to the cold war norm. Perhaps it never really moved far away from it. Both inter-Korean civil strife and international tensions continue to bind the peninsula to this day. And, as a new Hudson Institute study comprising the views of leading American and South Korean authors explains, the path to peace is not singular, but manifold. If peace is to be achieved, it will entail dealing with inter-Korean elements of civil conflict, as well as the profound international aspects that envelop and buffet the peninsula.

Peace is hard because peace is not just the absence of war. As the late British military historian Sir Michael Howard once opined, peace implies "social and political order.”4

Moon and Trump’s rush to the summit minimized the importance of complicated issues to search for agreement in other areas. Yet the complicated issues are what obstructs the establishment of a durable social and political order and lasting peace. Those unexamined hurdles are at least fourfold.

In the first instance, nuclear weapons remain effective deterrents against outside attack. Absent an ability to address North Korea’s fear of regime change or the ROK-U.S. alliance’s fear of another surprise attack, nuclear weapons retain a value that cannot merely be talked away.

Second, there is also the fact that the introduction of free markets in North Korea would delegitimize the Kim family regime. Yet, international financial aid and assistance are unlikely to pour into North Korea without the infrastructure and guarantees available in most free markets.

A third issue is that the ROK-U.S. military alliance is immensely important for both parties, yet neither is investing enough effort into forging a common vision for the future or accommodating each other’s needs. This relationship transcends defense but would lose its raison d’etre if it were not deemed a credible deterrent to a nuclear-armed North Korea, and the relationship could unravel if minor disagreements wedge the allies apart.

Finally, bilateral summits among the two democratic allies and North Korea cannot wish away the importance of China, and China refuses to yield its strategic influence over the future disposition of the peninsula.

All four of these issues are explored in Pathways to Peace: Achieving the Stable Transformation of the Korean Peninsula, which is just being released by the Hudson Institute. Bruce Klingner of the Heritage Foundation concludes that there is greater reason for pessimism than optimism regarding a diplomatic solution to the North Korean nuclear program." Yet "Dr. Jina Kim of the Korea Institute of Defense Analyses sees potential in exploring cooperative threat reduction as a means of slowly walking back the nuclear threat while simultaneously dealing with the Kim regime’s security dilemma.

Former Foreign Minister Young-kwan Yoon and Troy Stangarone of the Korea Economic Institute take complementary approaches to their subject of North Korea’s economic development. Both believe that the basic challenge is how to introduce market liberalization into North Korea while understanding that the economic dimension of policy is inextricably intertwined with security issues.

But as diplomacy with North Korea remains stagnant, and Pyongyang's WMD programs carry on, escalating U.S.-China competition poses an acute challenge to South Korea: Washington remains Seoul's main security guarantor, but Beijing is an essential economic partner. And as the United States presses South Korea to shoulder more significant burdens for the alliance, while also nudging it to look at China's emerging power, the Moon administration is grappling with how to preserve the ROK-U.S. alliance without jeopardizing its other interests. These severe and growing challenges to the bilateral alliance, often referred to by both countries as the keystone to peace on the peninsula and in Northeast Asia, are incisively analyzed by retired South Korean Lt. General In-bum Chun and retired U.S. Army Colonel David Maxwell of the Foundation for the Defense of Democracy.

Finally, Dr. Patricia Kim of the U.S. Institute of Peace and Dr. Seong-hyon Lee of the Sejong Institute offer sharp assessments concerning China’s role and relations with the United States and South Korea. Both authors are acutely aware that the three countries have different interests and different ‘end states’ in mind when contemplating the stable transformation of the peninsula.

Seoul and Washington may aspire to peace, but Pyongyang appears to want to cling to absolute power. Without a fundamental shift in at least the policy of the North Korean regime, the security dilemma of leaders and the interests of governments will remain separated by a chasm much wider than the demilitarized zone that still divides the two Koreas.

The world would fare better on the peninsula if North Korea could swap development for denuclearization. But as a global pandemic shrouds the latest opportunity to advance peace, perhaps we will never know.

Read in RealClear Defense