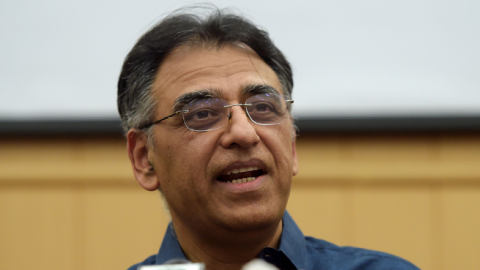

p(firstLetter). As Pakistan’s finance minister, Asad Umar, stepped down within a couple of days of announcing that Pakistan will soon get its 13th IMF bailout in 30 years, it is safe to speculate that the discussions with the IMF are not going as well as Pakistanis would like. Umar’s departure from Imran Khan’s cabinet has come in a virtual coup that has brought military favourites from previous regimes into office.

The Pakistani military has a view on everything, including management of the economy, although military officers are not trained in economic matters. The generals who really rule Pakistan cannot accept that the country’s resources cannot sustain an over-sized military and the periodic wars it initiates. Nor do they see the connection between their preferred policies, such as support for Jihadi terrorism, and declining investment or foreign trade.

Under the generals’ influence, Pakistan prides itself as a warrior nation. Investors and traders are looked down upon although in prosperous countries they are seen as drivers of economic growth and prosperity. Politicians and civil servants are frequently sent to prison for signing projects with foreign investors, along with cancellation of those contracts.

Tax collection remains low because land-owning politicians, often beholden to the military, do not agree to paying taxes. Loss-making public sector corporations, which provide lucrative post-retirement jobs to military officers, are neither shut down nor sold off even though their privatisation has been part of the promised reforms offered each time Pakistan borrows from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Economies grow amid stability, rule of law, enforceability of contracts, and security for both capital and the capitalists. None of those are available in Pakistan. Instead, policies are often driven by myths, such as the notion that billions of dollars of ‘ill-gotten money’ belonging to Pakistanis is lying in foreign banks that can be confiscated and repatriated by an ‘honest’ (read pro-army) leadership. Or, the fantasy that multi-billion-dollar projects like huge dams can be built by raising donations from well-meaning Pakistanis.

Pakistan’s military-driven economic decision-making is based on ‘Jazba’ (passion, spirit, and strong feeling or emotion) and Chanda (donations). In economic matters, Prime Minister Imran Khan has been a civilian advocate of the Pakistan military’s simplistic paradigm. His assurances to Pakistanis that they should not worry – “Aap nay Ghabrana Nahin hai”— have become a joke or a legend, depending on which side of Pakistan’s political divide one stands.

But economists look at hard numbers and are seldom swayed by the belief that God makes special provision for nations led by honest patriots. That is why Khan had to beg for $10 billion from Saudi Arabia, China, and the UAE to stave off a balance of payments crunch soon after coming to office in the hope that this would preclude his government from having to go to the IMF. That money is now running out.

Turning to the IMF is the economic equivalent of a sick individual being in intensive care. Considering that Pakistan has spent 22 years in the last three decades in the IMF’s intensive care, the country’s economy obviously suffers from some serious ailment. This might be the time to reflect on the source of the disease rather than focusing on the symptoms of the latest bout of illness.

Pakistan has battled budget and trade deficits for years. Its exports and tax revenues have failed to increase sufficiently, and its foreign currency reserves have never risen beyond the value of a few months’ imports. Pakistan has often borrowed heavily to make up for insufficient revenues and exports, increasing sovereign debt. In recent years, that has led to onerous external debt payments and a weak rupee.

Pakistan’s repeated knocks on the IMF’s door come whenever the country faces a balance of payments crisis. Pakistan has borrowed from the IMF 18 times since 1972. Compare that with only 10 IMF loans for Bangladesh in the same period. Pakistan’s IMF borrowings ran to an estimated $19 billion, while Bangladesh’s dealings with the IMF were a modest $2.7 billion. With rising exports, Bangladesh has not sought help from the IMF since 2015.

The comparison with Bangladesh is important because Pakistan’s Punjabi elite looked down on what was their country’s Eastern wing from 1947 until the Bengalis successfully fought for independence in 1971. On the eve of its independence, Bangladesh was more populous, more illiterate, and much poorer than Pakistan. It now has a smaller and more literate population and its GDP, which stood at $6 billion in 1972, has grown to over $249 billion.

While Pakistan invested in its army and nuclear weapons, Bangladesh invested in its people. Its literacy rate rose from 17 per cent in 1971 to 72 per cent in 2016, putting Pakistan’s 58 per cent literacy rate in 2018 (up from 22 per cent in 1971) to shame. The more literate Bangladeshis create a better human capital pool, which in turn allows their country to produce value-added goods.

While Pakistan still sells cotton yarn to the world, Bangladesh exports garments that fetch higher prices. Literate Bangladeshi tailors produce garments that meet foreign buyers’ specifications; as a result, cotton textile exports of Bangladesh, which does not produce cotton, exceed in value against those from Pakistan, which is one of the world’s major cotton producers.

Instead of addressing these fundamental issues, Pakistan’s generals constantly search for a well-connected international banker, multi-national corporation executive, or a former World Bank official who would straighten Pakistan’s balance sheet with a few more loans or donations. That keeps the Jazba and Chanda cycle going but does not create a healthy economy.

Just before he was forced to quit, finance minister Umar had been quoted in the magazine Euromoney, promising to end Pakistan’s addiction to the IMF. Ironically, the same magazine had cited General Pervez Musharraf’s finance minister, Shaukat Aziz, making the same promise while anointing him as ‘Finance Minister of the Year’ in 2001.

Euromoney, which has sometimes been accused of “surviving on soft advertorial” and whose “various annual awards seemed weighted towards clients that had bought the most advertising” also saw “encouraging signs of a sustainable period of growth” in Pakistan’s economy in April 2017, just before General Qamar Bajwa pulled the rug from under former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s feet.

If the army’s meddling did not allow previous IMF programmes to pave the way for sustainable economic growth in the past, it is unlikely that their latest efforts at engineering will result in anything better.

A new finance minister might be able to borrow money from the IMF on different terms than the outgoing one. But at the end of the day, Pakistan will have to address its huge military burden, poor social indicators, and unreliable investment climate or remain on life support.