A Requiem for Dominance: New US Strategies to Deter Aggression

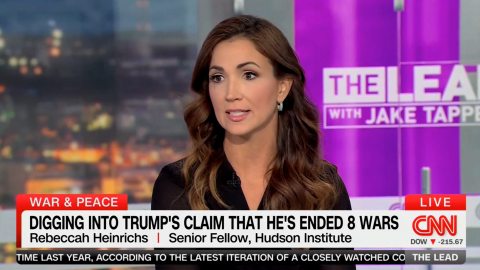

Senior Fellow and Director, Center for Defense Concepts and Technology

Bryan Clark is a senior fellow at Hudson Institute. He is an expert in naval operations, electronic warfare, autonomous systems, military competitions, and wargaming.

Adjunct Fellow

Ezra A. Cohen is an adjunct fellow at Hudson Institute, focusing on intelligence policy.

Former Commander, Office of Naval Intelligence and Former Director, National Maritime Intelligence Integration Office

Pentagon assessments and think tank studies continue to highlight the erosion of the United States military’s dominance over a growing and improving Chinese force. Decrying the loss of American primacy, government officials and analysts now call for dramatic increases in defense spending and greater investment in the industrial base to sustain US overmatch. But attempting to field a larger and more capable force than the People’s Liberation Army in Beijing’s backyard is likely the wrong way to deter aggression against US allies such as Taiwan or Japan. The US military—and the US government more broadly—needs a new approach. A new Hudson Institute study, Campaigning to Dissuade, proposes one such approach, which would use available and emerging technologies to attack China’s operational strategy, prepare for a protracted conflict, and campaign to undermine Chinese military planning and confidence.

Hudson Senior Fellows Bryan Clark, Dan Patt, and Ezra Cohen will discuss the challenges facing US policymakers and new strategies for deterring Chinese aggression with Rear Admiral Mike Studeman (USN), former director of intelligence of the US Indo-Pacific Command and former commander of the Office of Naval Intelligence.

Event Transcript

This transcription is automatically generated and edited lightly for accuracy. Please excuse any errors.

Bryan Clark:

Welcome to the Hudson Institute. I’m Bryan Clark. I’m a senior fellow here at the Institute and Director of the Hudson Center for Defense Concepts and Technology. We thank you all for being here today, both online and in person for a discussion about US deterrence of China and some of the challenges facing us there. It is notionally about the recent report that we released on Campaign to Dissuade, but more importantly, it’s about looking at some new approaches for how we might be able to deter China given the eroding nature of US military dominance and some of the opportunities that are presented by emerging technology.

So with us for this discussion, our rear Admiral Mike Studeman, who is the former director of Intelligence at Indo-Pacific Command. Most recently the former commander of the Office of Naval Intelligence and also a long serving naval intelligence officer with many storied positions, including being the first senior intelligence officer for China in the Office of Naval Intelligence, as well as serving as a special assistant to the chief of Naval operations, as well as the Commander of Fleet Forces Command and many other positions. Also with us is Ezra Cohen, former acting deputy, rather former acting undersecretary of defense for intelligence in the Trump administration. And also my colleague and co-author Dan Pat, who wrote the report with me Campaigning to Dissuade. So thank you gentlemen for all being here today, and I’m looking forward to this discussion about new approaches for dealing with the challenges posed by China. So Mike, let’s start with you.

The study that we just released kind of talks about the eroding nature of US military dominance, the challenges that China poses, both in terms of its geographic advantage as well as its numerical and potentially economic advantages. So where do we stand right now with regard to our ability, the United States ability to deter Chinese aggression using the traditional approaches that we’ve mounted for the last 20 or 30 years, such as deterrence by denial?

Mike Studeman:

Yeah, thanks Bryan. Bryan and I used to be in the same company at Officer Canon School back in 1988, right here. So if we were back then and we were projecting ourselves forward, I don’t think we would’ve found ourselves-

Bryan Clark:

Sitting in these chairs.

Mike Studeman:

Sitting in the chair. So I trust Bryan implicitly. We worked together on the Navy staff in a lot of capacities, and Bryan’s been working these issues for a lot of years and contributing some really astounding intellectual thought and giving considerations for not only the Navy but the joint force and the challenges are legion with regard to our peer competitor with China. And I agree that we need to be looking at all forms of influence that will prevent a combat environment or a crisis that will in fact be devastating for the globe, not just for China, not just for Xi Jinping’s own position. I think that if he tries to go after Taiwan, ultimately what will ensue will lead to the downfall of the chairman and the party secretary. And I think he underestimates this, but what we know is that if you take a look at the correlation of forces, you take a look at what would ensue with multiple players, that there’s no real winner in any of this.

And so where we need to invest our time and energy is in prevention, in the right kind of thoughts and clear understanding because miscalculation can lead you down paths and they can be spirals that ultimately might tempt somebody to take a military solution to something that I think would be catastrophic. And so how do you actually prevent, this is the main strategy. Now you need to have capabilities to prevail. And so the DOD is investing in long range fires, a number of things that are designed to be able to ensure that we maintain the right capabilities needed for any contingency. At the same time, a lot of our efforts need to go into the shaping elements there, and I do believe we have a number of things that are underway that way, but the Townsend environments that we face today means that you don’t stop your adversary from doing something, right?

You want to shape it so that they don’t take the most extreme action. So what can you live with? What can you tolerate and what can you not tolerate? When do you need to move? What are the triggers for you to then be able to bring more capability forward or work with your allies and partners forward to be able to handle any kind of situations? These are tough challenges and everybody’s working through it. I’ll just tell you that China’s behavior right now has been the most destabilizing element of what’s happening in the Western Pacific. And so everybody’s concerned and everybody west of the international Dateline is highly attuned to ensuring that China doesn’t miscalculate.

Bryan Clark:

So in a lot of ways we’re talking about competing in this confrontation that’s preceding war. I mean, I think a lot of the defense department’s focus has been on how do we deny an invasion once it starts and as a way of somehow implying to China that they will never succeed and therefore they shouldn’t try. But that approach leaves open this whole battlefield, if you will, of confrontation in the meantime and allows China to gain in that competition. So Ezra, you’ve had a lot of experience going back in your pre under-secretary days in the special operations world, in the intelligence world. I mean it seems like a lot of the opportunity space here is in this sort of persistent confrontation that we see that China’s been acting on or implementing or initiating in a lot lot of cases. But it seems like we should be in there as well in that fray.

Ezra Cohen:

And I think that the department has made some positive moves towards institutionalizing irregular warfare. That’s the lingo. I do think that more needs to be done. Right now, the Chinese have really engaged in quite a sophisticated irregular warfare campaign against the Pacific, in the Pacific for the past 10 to 15 years. During that time, we were obviously, and our forces that would normally conduct these sorts of regular warfare operations, at least the core forces were obviously very focused on the global war on terror. Now that that has largely ended, it is an opportunity for us to refocus those special operations forces on conducting irregular warfare in the Pacific.

I think that one of the advantages of irregular warfare is that it allows us to create many, many off-ramps to conflict, and it also allows us to push the adversary towards an off-ramp, not just create an off-ramp, but actually push them, actively push them towards an off ramp. And I think that Bryan, in your paper, you do a very good job of discussing how through irregular warfare, which by the way is much less expensive than a high-end conflict, we can create the environment that will keep things pre conflict. And that’s really what the objective is, keep all of the activity, prevent it from going to conflict. And I think that that’s really where the department needs to do more on the irregular warfare front,

Bryan Clark:

Which it seems to make a lot of sense, but unfortunately that’s not where our effort has been. So Dan, why is it that the department seems to be foresighted on this idea of stopping a Chinese invasion and that’s the forcing function that we use to guide the entire defense budget. And then why is it that doesn’t work anymore as a deterrence option? Because that’s what we’ve done against previous competitors that we faced post Cold War?

Dan Patt:

Yeah. Well first of all, it’s great to be here with unconventional thinkers like you two. So a pleasure to be here. Well, look, I mean we can all agree that the department does foresight on this Taiwan invasion scenario and we can all agree this is undesirable and the department has a role in preventing this or if this does happen attempting to prevail, right? That’s something we can agree on and that’s natural that the department goes there, it’s force planning is built around that. How much do I buy? What do I buy? This viewing things through this kinetic lens. But if we go back to how exactly do we invest in prevention, and one theme that I’m particularly excited about is a role of technology not just in better weapons, but technology for deterrent itself, technology to support irregular warfare, technology to support shaping and signaling, technology to support understanding of whether or not we’re near an escalation threshold.

But these things are very difficult to do force planning around to fund in the budget because there aren’t, it’s right at the intersection of operations and intelligence. There’s not obvious entities in the department associated them. There aren’t program offices, there aren’t funding lines. So it cuts the other way from how the department itself has been structured. So we struggle to shift gears and we stay in our comfort zone where it’s very clear there’s a very clear scenario that’s undesirable.

Bryan Clark:

And there’s also a lot of equities outside the department over in Congress, over in the defense industry that are advocating for the more traditional approach because that’s something they can plan against as well as something they can make money against. Mike, you mentioned a lot of things we could do to sort of prevent conflict in the intervening time. So first of all, a lot of people have been raising alarm bells that China is imminently going to invade Taiwan, although it doesn’t seem like there’s much evidence to that effect that they’re getting ready to just pour into the ocean right now. But are we in fact looking at imminence in terms of the invasion of Taiwan? And if not, well, what are the things we can do to forestall that possibility?

Mike Studeman:

Yeah, I think we need to back up a little bit and say what motivates China today to increase some of its harassment and intimidation activities? And if you’re on the other side and you’re in Beijing, you’re seeing what amounts to walking away from our one China policy. There’s more chatter than ever about solidifying Taiwan’s de jure independence. People are talking about strategic clarity. There are more and more visits to Taiwan. The Chinese, very tone-deaf, almost autistic in this regard, with regard to whether or not their actions created some other actions. They didn’t never see themselves as causal. So you have this massive buildup of the Chinese military, then it’s deployed across the first island chain and beyond, and then doing many coercive things as we know in South China Sea and Senkakus and other places, claiming the Taiwan Strait, claiming these vast stretches of extraterritorial places in the sea.

And it’s got everybody concerned. And therefore the natural reaction is to increase your defensive capacities. Is to maybe get more realistic with your training and then work with your partners, whoever they might be. This is exactly what Taiwan’s doing. Japan’s doing the same thing. The Philippines, the list goes on throughout all of Southeast Asia, and so China doesn’t see that they’re at fault. What they just see is all these actions that are designed to contain them, to encircle, that there is going to be a new NATO in Asia, and then they push harder because they see that they need to break out, have the freedom of action and to achieve the rejuvenation and the dream that they have set out for themselves. And so there’s this weird sort of perceptions element there, which then gets to your point of, well, how do you shape those?

And those are very sticky, in fact, because you’re dealing with a very totalitarian government, you have a dictatorship. It used to be a one party dictatorship, but under Xi Jinping, it’s now one man, dictatorship is very clear. Go check your political science definitions. And so in this system how information moves, who’s willing to speak truth to power, those things tend to be harder in those kinds of systems. And so you don’t know what kind of information flows, so who is the ultimate decision maker about what to do next? Do I increase my forces around Taiwan to try to exhaust them to signal to the United States that there’s a penalty for apparently moving towards changing the status quo? The military is being used in a way that no other instrument has been effective in shaping matters in the Chinese mind. Economics hasn’t done it, informationally, warnings, diplomacy hasn’t done it.

And so they’re left with the military instruments and they’re using that very actively to say, if you don’t hear me, hear my concern and see that you’re approaching a red line, that I’m going to use the military, and we’re going to have to do it in very strengthened ways, including missiles flying over Taiwan to demonstrate a political point that they want to arrest what they see as a negative trend towards increasing Taiwan independence, like defacto maybe shifting to dujour. That’s going in the wrong direction for the Chinese. Therefore they’re acting to bring that back in.

This is the fundamental perception and the thinking that then requires you to go look at yourself and say, well, what does American policy and statecraft need to look like in this sort of environment? And sometimes your best tool is not a big military platform or something made of steel, that you end up moving it in a different direction. That needs to be complimentary to things that may be related to not integrated deterrence, but integrated assurance. And integrated assurance doesn’t just get focused on your allies and partners, but sometimes it has to be focused on your opponent, whoever it might be. So we need to assure Beijing that we aren’t doing something that changes the status quo of Taiwan. It’s the fundamental kernel of insight that you need to have as a starting point before you figure out what is my next move.

Bryan Clark:

So just a quick follow on. So does this mean we need to leave open the possibility that China could achieve some kind of peaceful unification with Taiwan? Because when we’ve presented that concept to folks inside DOD and the government, there’s a lot of resistance to that. The feeling is, well, we can’t let them get any control over, or any more influence or control over Taiwan, that’s unacceptable to the United States, which seems like you’re setting up the need for confrontation because Beijing will see confrontation as the main path to achieve their objective.

Mike Studeman:

Well, look, Washington didn’t set out to put Taiwan on the agenda. They’ve worked with the Middle East issues. They had Ukraine and Europe and Russia and the invasion, nobody sent out to actually, let’s lift up the Taiwan issue and let’s agitate that we can actually solve this problem. In fact, our policy remains the status quo with Taiwan is where our ultimate objective lies. No change except providing enough defense armament to ensure that the PRC doesn’t think that they can actually move quickly and conduct a theta comp plea. You have this massive military, you need a little bit of help to Taiwan to provide for its own defense. That’s what it calls for in the Taiwan Relations Act. So that’s what we’re doing. The status quo is being changed by Xi Jinping who has said that Taiwan has to be recovered to be part of the rejuvenation by 2049. He has unilaterally set out to change the status quo and has started to build a capability to do that. This is the fundamental issue at hand is that it’s not about our policy, it’s about Beijing’s policy.

Bryan Clark:

So Ezra, if this is about China having this perception that they are being sort of pressed back or pushed back by the US and its allies and their behavior, how do you start to shape that in a way that makes them less concerned about that without backing down? The US can back down and be very conciliatory, which seems like that’s one path, or try to convince allies in the region to be more conciliatory, but that seems like that’s probably not the desired path. So how do we go about trying to assure China without undermining assurance of our allies?

Ezra Cohen:

So I think the first thing, and Mike I think started to point at this, which is this really comes down to Xi’s decision-making process and we need to improve our understanding of that decision-making process. You don’t just do that through intelligence collection, you also do that through what you talk about in the paper, which is probing and doing things to elicit certain responses that would help us understand the decision-making process better, but also for us to shape the decision-making process as well. And so I think that that really needs to be step one. Right now there’s a lot of talk in the US about deterrence. The problem is everything we’re doing doing and all the money we’re spending isn’t deterring anymore. It’s actually increasing the hostility. So one of the things that we need to do, and I think part of that also has to do with our understanding of what Xi’s risk tolerance is.

So that’s another part. It’s not just the decision-making process, it’s also understanding his risk tolerance. Once we have those two things, a better understanding of those, we can then start crafting actions that actually will create the off-ramps, avoid conflict. And frankly, I think a big part of this too, Bryan, is the US has, and there’s been a lot of talk in the US kind of intellectual foreign policy circles for the past 20 years on this idea of regime change, knocking off our major opponents. That of course is not, if Xi genuinely believes that that’s our aim, not just maintaining the status quo with Taiwan, but if he believes we want to go farther than that, we can say goodbye to this idea of keeping everything pre conflict. That will almost certainly guarantee that there is a very, very deadly shooting war.

So I think that that kind of gives you a few ideas. Again, sailing in aircraft carrier and putting all of these sorts of armaments right into their face. Sure, it shows that we have the ability to project force, but I think we also need to be more mindful of what that might be doing to Xi’s decision making and I don’t think it’s creating the effect that we actually want.

Bryan Clark:

Mike, so you mentioned that we’re doing a lot of things today that are trying to influence or shape the environment during this peace time or competition period. It seems like what might be missing is that feedback loop of understanding how those actions are affecting decision-making and risk tolerances and perceptions inside the Chinese government. Do we have a way of, or do we try to implement that kind of feedback loop? Are we trying to create essentially the control theory model where we can see the impact of our actions and eventually be able to understand what might be happening inside the black box?

Mike Studeman:

I mean, it’s the reason that the intelligence community exists is to have strategic intelligence and insights and allow us to have those feedback loops so we can make sure we can monitor and adjust our policies if they’re not actually achieving the right effects. So we have hard target countries that are closed societies, paranoid, that are good at OPSEC, operational security, and China is tough to truly understand. And so we have good insights because the money that the taxpayer spends on the intelligence community goes to amazing things that if you knew what we were capable of in terms of learning these insights about others’ intentions, you’d be very proud. At the same time, we don’t have enough and we need to have greater understanding so we can map out sort of decision-making circles and who influences who and how choices are made. And we’ve seen evidence that in fact, that information doesn’t flow as quickly or as cleanly through the Chinese system.

And we get the reactions that tell us that in fact they probably don’t actually know what happened here or there. And so we are knowledgeable enough to know that that system is clunky and that there’s no way to potentially sort of guarantee that you can get the right sort of information in at the right time. And this is the scary thing with regard to the Chinese view towards cutting off communications with the US military not having hotlines. Their belief is that, well, first the US attitude ought to be improved.

You got to respect China. You got to not say bad things about China, and then maybe if we can trust you, we’ll have a line open to you. They also believe that if we have a hotline, that we’re more prone to risky behavior because that’s our kind of safety net. And so don’t give the Americans a safety net to say, Hey, they created a crisis and then they want a house, they want an ability to negotiate their way out of it. Just don’t give them a safety net and then maybe they’ll be more conservative with their forces and their behavior. All of this, whatever the logic is, leads to very little official communications now, even down in the track 1.5’s that become few and far between. This is a very dangerous trend in terms of our ability as major powers to truly work out our issues.

Bryan Clark:

Right. So Dan, is there a way for us to employ technology to help to improve the ability to generate this feedback loop in the absence of maybe some of the official communication channels?

Dan Patt:

Yeah, absolutely. First of all, I think even if there are no phone calls and formal communication, there is signaling that happens every day. The US may not always be aware of how our actions are perceived. We may not be aware of all the signals they’re putting out and vice versa, as you’ve talked about, right? The PLA is likely not aware of all of that. So one, it’s important to recognize there is that foundation of communication today. And second, of course we have a remarkable intelligence community, but there’s this frontier of being able to collect more data and operationalize that and push that information to a broader force, more military commanders, others across the government who are then able to inform or shape their actions by it, working towards some model of mission command around this. And this is really where I think there’s a real potential for technology.

One of the things that happens all around us is as computers and information systems become ubiquitous, these put out signals and there are so many more signals than there ever used to be. A simple example is we can take commercial EO satellites and commercial radar and we can process those images to get change. So was there something built here or not? And that’s from a pure commercial source. As we start to understand this ability to create new indicators and warnings that are appropriate and push them forward to across the government and to military commanders, I think it’s really exciting to both be able to measure a baseline and help us understand at a more granular and a more real time level how things that we’re doing are affecting this baseline or how the baseline is moving.

Bryan Clark:

So Ezra, it seems like one of the challenges that implementing Dan’s approach would involve is how do we actually orchestrate this on the US side to be able to take a probe, evaluate the response, turn that into a recommendation for another probe? Because I think to sort of get to Mike’s point of how do we understand the decision making process, you need this iterative set of actions and reactions to eventually narrow down the entropy or the uncertainty.

Ezra Cohen:

And it needs to be done a hundred times faster than we’re doing it now. We can’t wait 30 days to respond to something unless that delay is intentional, right? I have no problem with intentional delay. I have a problem with unintentional delay, which is where we seem to be kind of stuck right now. I think the biggest thing is there’s no question that if this gets to conflict, there will be a global combatant commander for China. There will be one person that’s clearly in charge of the effort. The problem is we don’t want to get there, we want to avoid that we’ve been talking about. So I think really what we need today is one person. I do think we need somebody who is singularly responsible for countering and engaging in this pre conflict activity with China for commanding that on our side.

That’s one thing. And one of the reasons for that is simply that to be successful in this pre conflict stage, it’s not just about what the US military is going to do, it’s about what the entire power of the US federal government is going to do. And being able to chain together a US military action with a, I don’t know, a DOJ action or an action from the Treasury Department, being able to do those things in concert is extremely important to being successful in the irregular warfare space.

And that cannot be done under the current construct we have in the government. There needs to be one person responsible. I think the other thing too is there’s just a fundamental authority problem, which is that all of our legal analysis and the way we conduct legal analysis over whether or not an operation is legal centers around this idea of what’s the likelihood of escalation? Well, if our understanding of escalation as we just talked about is completely off, then we’re always going to get to the answer that the new operation, that the potentially more effective thing is not permissible legally. And so we’ve kind of found ourselves in this very loop that’s just stalling us out because of that. And so I think to break out of it, again, we talked about this a little bit before, but I think that one step towards breaking out could be to have just a singular person in charge, and we’re missing that today.

Mike Studeman:

Can I comment on that? So I do think all roads lead to the National Security Council staff and the president and how they want to conduct their relationship with China, what they want to have veto rights on and what they want to allow mission command to be and to do. And you find that the sensitivities are so high today that I think that there’s a deep concern about not holding very closely everything significant with regard to China and to focus on as part of our major strategy to work with our allies and partners and simply work with the good guys and to be able to build up capacities and to deepen relationships and to be able to create an environment which demonstrates in fact that there are a number of partners that would be unwilling to allow violence or intimidation to rule the day anywhere, but particularly in a sensitive area with the economic engine of the twenty-first century there in Asia.

The problem is that there’s so much that our society is unaware of with regard to China, and there are many allies and partners who are unaware of many of the Chinese activities. So if you have overly tight controls in the information domain, which is key, so your insights that you learn may feed into, I want to adjust my ability to go test and probe over here. Those are tactical and operational elements. The strategic game is to use your information power to be able to highlight what your adversary is doing, which violates international norms or would exact reputational damage on them such that it shapes them to say the costs for doing this again and again are higher than thinking about some other means, some other method.

And today, if you look at the information domain, we are under utilizing this instrument of national power because of our tight controls and our inability to delegate and trust that there are a number of agencies and departments that in fact would stay within the boundary lines, the left and right guidance lines that would be issued from seniors, and to be able to then do the job of rapid exposure of malign actions in the irregular warfare zones, which all of our friends care about.

Our sensing systems are not perfect either, which means that we have to be able to get more eyes and ears forward than we do. We have invested in too many big platforms that are slow lumbering and they can’t get to the right places. We need more persistent stare, which requires more numerous ways of sensing that we can do so with our partners and a sharing regime, which then allows us to know exactly what the next move has been, and if necessary, taking the video clip or the photo showing the Chinese water hosing a Philippine ship or a military lazing Australian aircraft or dumping chaff into the jet engines of a P8 from Australia. Those are the things that the information environment should be exposing so that Beijing has to own them, right? Because ultimately you want to condition that country to be a true responsible stakeholder, and you want people to understand what their intent and their activities truly are, not just what they’re saying from their podium.

Bryan Clark:

So just to follow up on that, so the idea of using this sort of exposure, naming and shaming, I guess for lack of a better term, but is that going to be sufficient to cause China to back down on its more aggressive actions and the potential for it attacking its neighbors?

Mike Studeman:

I think using that instrument is better than not using that instrument in terms of providing a convincing case and evidence of what China’s behavior looks like. And so will China stop? Probably, in some areas, not if the strategic objective is to continue to intimidate Taiwan, they’ll probably pay that price, but the rest of the world is watching. These other nations that don’t have the benefit of actually knowing what’s going on. Our responsibility if you have more premier intelligence capabilities is to share that large asset and the insight that you have with a number of people, it’s not good enough to keep it within classified channels so your own decision makers are the most omniscient. You need to use the information for effects, and that requires a sense that you have to use it quickly before it becomes perishable.

Bryan Clark:

And this can also be a tool for being able to, this could be a probe in its own right. This is a way of revealing or watching how the Chinese respond to it to see, well, what do they appear to be neuralgic about? What are the things that cause them to react and maybe pull back as opposed to things that might cause them to be even more aggressive?

Mike Studeman:

It highlights the true character of the Chinese, the true nature of their activities, and people want to understand the nature of the danger. If they understand the true nature of the danger, they can do long range planning. If you’re in Indonesia or if you’re in Vietnam or you’re in Philippines or anywhere South Korea, you can figure out what your investment strategy needs to be along with your policies to be able to deal with what is a genuine depiction of the nature of China’s rise. Everybody’s in search of understanding the ground truth.

Bryan Clark:

Ezra?

Ezra Cohen:

Yeah, and I’ll just say it’s not just about can we share the intelligence or the information we have with the leaders of our allies and partners in the region, but we really need to inform the populace in the region. Obviously in the irregular space, that’s extremely important. If Xi does decide to push this towards war, knowing that the population in the region is not going to be very kind to him, that that’s something important and we need to create that condition. I’ll say that I think that this idea of this rapid ability to just rapidly get information out to the population, it’s something that really DOD and the State Department have to work very closely together on, and the intelligence community. And that’s really a place where I hope that technology can help us get over that coordination, this coordination inertia that we’re really stuck in now. And I think that’s what you’re alluding to.

Bryan Clark:

Yeah. So Dan, I mean, do we have ways of being able to get information to allies, partners, populations more quickly? I mean, I was obviously things like Voice of America and Radio Free Liberty, et cetera, but are there other mechanisms that might be at play here that can be used in an era when also there’s going to be an increasing number of DeepFakes and AI generated content that could be perceived as this is just another example of that.

Dan Patt:

Yeah, I mean, I think this is one of the most exciting areas for the DOD. There’s so much potential in technology here. I mean, what we’ve all witnessed over the past 20 years is this explosion of commercial technology in compute and analytics and algorithms and communication and that’s sitting on the floor. It’s free for the taking, it’s free for DOD and the IC to apply for this and absolutely. Rings of networks to be able to share with our most trusted allies, with other partners and allies together. I think those are very powerful tools. Those are very low cost. These cost orders of magnitude less than developing new weapons. And then from there, of course, you’re able to start to take input from those partners and allies as well to build a more complete picture and to deploy analytics against that. Yeah.

Bryan Clark:

So in the report we talk a little bit about the idea of trying to use probing and actions to create uncertainty for China with regard to its likelihood of success in particular military actions. So it seems like what you’re saying is that we, instead of creating uncertainty for the Chinese, we need to create certainty in that we’re trying to assure them that we’re not only going to publicize their actions on the world stage and make them available to allies and partners. We’re going to continue to do that going forward, and we’re going to always be providing this watchful eye on their behavior.

Mike Studeman:

I mean, we had this phrase about providing strategic predictability and operational unpredictability. This is supposed to be a guide for us. The Chinese see operational unpredictability and strategic unpredictability. See the dilemma? The dilemma is that we need to work on our strategic part of it. And so where do we stand? Is it status quo for Taiwan? Where do we put a stake in the ground and make sure that there’s no confusion? Because our debates among the elites with regard to Taiwan provides a very confusing set of signals to them, including the debates that exist in Congress. And so then you get the visitation that suggests that we’re going to treat Taiwan as a defacto nation. That’s the political elements there. So we need to do appetite suppression on the political and strategic activities to carry the highest symbolism that force China to think whether or not we’re actually living up to our words.

If they don’t believe that we are in a status quo environment, then we have a problem. And keep in mind the paranoia people that exist in the CCP, Chinese Communist Party, are inclined to not believe your first explanation that there’s got to be some other here. So they’ll discard the first even if it’s true. And so we need to work on ourselves. This is look in the mirror and find out whether or not we need to do strengthened conversations with the Congress to understand that just sending CODELs after CODELs over there, whether or not that’s wise or it’s not, is it going to lead to something beneficial or is it simply creating more unnecessary friction and doesn’t actually help the problem?

Are you accelerating our crisis or are you decelerating your crisis? And so I do think that whether you’re in the executive branch, whether you’re in the legislative branch, whether you’re part of the military or other agencies, we need to look hard at whether or not we are doing what we need to do to send the clear signal, the honest signal, and live up to that with astute statecraft. So these other things are going to be moot. You can try to shape and expose behaviors, but fundamentally on this particular core issue, if they believe, if China believes they have to act because otherwise time isn’t on their side, right, then you’re going to head right down that funnel into something that we talked about earlier, which is not good for anybody.

Bryan Clark:

Right, so Ezra, in terms of operational unpredictability or operational uncertainty, what’s the tool set that we have there? And is that operational uncertainty just in terms of military operations, or are there things we can do in the economic and diplomatic or information world that create that tactical level uncertainty without affecting the strategic relationship?

Ezra Cohen:

So I think what you’re getting at Bryan is this idea that we obviously want them to understand, and this is what Mike was saying too, we want them to understand where we are going to go, but we also need to use, and we do have a lot of tools both in the cyber realm, all throughout our state craft and economic tools that we have at our disposal, at least creating enough. I think it’s actually, there isn’t room for uncertainty, and it’s the uncertainty in that first level of decision maker around Xi Jinping, if Xi feels that, one, either he’s not getting reliable information or the people around him don’t really know what’s going on. I think that will affect his ability to make a decision and at least make the decision to go into Taiwan. I think that there’s a lot of places that we can really increase our efforts there.

Again, this comes down to having a coordinated government strategy, and it’s really the campaign idea, but it’s not just a DOD campaign. It’s really a government-wide campaign and we need somebody to bring that all together. How do you pair a cyber action with an economic action? Right now these things are loosely coordinated, but they’re not really happening in concert.

Bryan Clark:

So Mike, if we try to create uncertainty in that inner circle that Xi must rely on for information and advice, is that potentially highly escalatory? Is that a problem or is that really an area we should focus our efforts or should we try to keep stability and certainty at that highest level in terms of our strategic level actions and intents, and then focus our uncertainty efforts at the tactical and operational?

Mike Studeman:

Yeah, I mean it depends what you want them to be certain or uncertain about. I mean, I want them to be certain that if they try to do something violently and against their promises, go back to the seventies with regard to Taiwan, that there will be a certain level of devastation and that their results will be not just uncertain, but will likely in fact onboard a major defeat, an imbroglio like they’ve seen in Ukraine. The Taiwans are now wise. So they watched Hong Kong, essentially the freedoms crushed in Hong Kong by China’s own choices, and they are now awake, I would say, and they are on path to maintain their own system of democracy right now. And so I think that there’s enough evidence that the reaction would be devastating militarily. And I think what we learned out of Ukraine was that don’t underestimate the democracies that unite, no matter what the history has been, unite to be able to rise up and demonstrate and signal their displeasure.

And I think you’d find that not just in Asia, but I think you’d find that in Europe. And so if you’re in Xi Jinping’s position and you’re thinking, well, I can just do, I can get my military ready by 2027, and then when the geopolitical conditions look good, if I then can move, I’ll move. The issue would be a high level of uncertainty. Not only that militarily, they can successfully do a quick operation, but secondarily that every other major Chinese objective that they’ve set out for themselves is going to be jeopardized by this one particular operation, including Xi Jinping’s own individualistic desire to have a legacy greater than Mao Zedong, that those would evaporate like that. And so that’s the certainty that you want them to have and actually is the most probable, most likely outcome. You’re talking today in the late twenties or the thirties. So I don’t want certain things to be uncertain. Right.

Bryan Clark:

And that really gets to your point, that there’s tools on the economic and diplomatic and information side that can help promote that certainty that the international response will be such that it’s going to undermine Xi’s opportunities to pursue as other objectives and goals.

Ezra Cohen:

And that it will ruin his legacy. I mean, the idea that, and I think there’s ample evidence out there, but perhaps the Chinese aren’t perceiving it, and that’s something we need to figure out how to do more of, that this will not cement Xi’s legacy. This will lead to really the kind of downfall of his legacy in the eyes of the Chinese people. But the key thing is his decision will be based on the trust that he has in his forces. And I think that that’s really an area of focus that we need.

Bryan Clark:

We’re going to, I’m going ask audience questions here in just a minute, so if you have questions, start formulating those and we’ll call on you in just a minute. So Dan, but to build on Ezra’s point operationally, we could create a lot more uncertainty for China with regard to how we’re going to operate or their likelihood of being successful an invasion on the terms that they would find acceptable. So what are some of those things and are we doing those things today?

Dan Patt:

Yeah, maybe I’ll just briefly zoom out and say I don’t think so, Bryan. I don’t think we’re doing enough of that. And I think that’s at least partially because we have a narrow view on this notion of denial and deterrence by denial. And it imagines that there’s this binary trigger for war, that there’s an amphibious invasion of Taiwan, and it triggers a military response of course that comes across and encourages the US to plan around that. So not only do we think about this scenario, we do forced planning around the scenario. We think about what to buy and what to deploy, and it ends up acting as a form of prevent defense. We take all of our resources, we put them all in the goal line, stand against this one scenario. Of course, what it discounts is that there are many possible scenarios that could happen, some which always stay below the threshold, others like a quarantine scenario or island incrementalism, which are more ambiguous and maybe provoke other things.

And so not only does it drive our force planning and what we buy, in that direction also drives how we operate in predictable ways. And of course, if you think that there are other scenarios which are possible, you need to have forces which are ready to act upon those other scenarios, which means that they need to be able to train and develop alternative ways of operations. So you can think about this as yes, operating our forces in ways that could generate continual surprise or be able to drive the operational uncertainty that the admirals spoke to. And again, technology can support that.

Mike Studeman:

I just offer, I mean a lot of things that we do in the Indo-Pacific have been obvious to many, and then there are many things that we’re doing in our campaigning that actually take what Dan’s talking about and puts it in practice. I agree with the sense that we can scale that up, but those concepts are well entrenched within the thinking and the planning for the Pacific fleet, for the components all the way through into Paycom and all the way up to the OSDP and the NSC. And so that is underway. I’ll just tell you would be proud of some of the ideas that have been converted into the thinking there and with a sense that the other guy is going to be working their AIML to be able to use machines to aid predictability.

And the whole notion of making sure that you give data to those machines now so that they are completely on the back heel, right? That is a notion which is translated into a number of different operational planning activities. So we have a keen sense of how to play that, and I think you can trust Admiral Aquilino as the INDOPACOM commander, Admiral Paparo, the genius of the Navy. I think that he’s exactly in the right spot to be able to implement some of the ideas that you’ve talked about.

Bryan Clark:

So I’m going to see if there’s questions from the audience. So we’ll bring the microphone around, but if you want to state your name and affiliation, I’ll go from right to left. So over here, we’ll start with you sir.

Audience Member:

Given that the PLA has been pretty obsessed with cognitive warfare for a couple of decades and that the strategy is built around that, how do you think they’ll respond to something like this?

Bryan Clark:

Great question. Mike, do you want to talk about cognitive warfare?

Mike Studeman:

Well, I think that this is embedded in the Chinese doctrinal approach there, and I do believe that they’re throwing their levers. They’re throwing their instruments to be able to engage in it. Look, we’re debating this kind of thing in talking about China and Taiwan. We haven’t talked about anything else China’s doing. Any of the other global challenges have faced us and our strategic interests, the penetration of our society, how Hollywood is essentially owned. So you can’t talk about China, you can’t do a movie or a TV series about China because they have penetrated. So the east is influencing the West, not the other way around, in serious ways, but here we are talking about just one single threaded issue. That to me is effective cognitive warfare when your propaganda and your tools of penetrating a society are so deep that we can’t have a lot of open discourse about China and we can’t have the entertainment industry or our basketball teams actually express their first amendment rights to talk about different things. I mean, that suggests to you that Chinese cognitive warfare has been pretty darn successful in our country.

Bryan Clark:

Yep, that’s a good point. And then in the little bit of work that we’ve been doing in cognitive warfare, I think most of the focus ends up being on individual. People tend to think of this as brain control, mind control of individuals. Instead, it’s much more effective when applied to societies or to populations, at a population level. Right, right, right. Exactly. Next question, you sir.

Stanley Cober:

Stanley Cober, formerly Hudson years ago, whenever I hear a discussion like this, I think back to Vietnam. We had CEDAW treaty, Tonkin Gulf resolution, north Vietnamese were not deterred. We bombed North Vietnam, rolling thunder. They were not deterred. Why do you think deterrence will work better with China now than it did with North Vietnam?

Bryan Clark:

Good point. Well, I have some thoughts on that, but Ezra, you want to . . .

Ezra Cohen:

Yeah, so I think really what we’ve been talking about today though is that the things that are currently being hatched up and this idea of deterring through just overwhelming force is not working and that really what we need to shift more to is shaping Xi’s thinking such that he does not take the actions that will lead to war. Not that we are going to just with overwhelming force scare him off of that. I think there’s a bit of a difference there, and that’s really what I know that Dan and Bryan have been looking at is technologically how can we do that and how do we make better acquisition decisions that don’t create deterrence, but change the thinking of the adversary? And that’s a bit of the difference. I don’t know if you want to . . .

Dan Patt:

Yeah, no, I think that’s really well said. I mean, look, the reality of the matter is that if it was really just a threat of overwhelming US force, that threat of US dominance is eroding. China has the world’s biggest navy, they’re able to field targets faster and cheaper than we are shots on targets. So there has to be something different and there’s tremendous opportunity for the US to be able to achieve its objectives if we shift to focusing on operational uncertainty. And if we focus on shaping decision-making,

Mike Studeman:

I would just say they’re all forms of deterrence. And so the economic instrument is probably the most powerful. And so the question of how to potentially use that comes up, and I think that the Chinese are very wise to that, and they’re trying to insulate their economy from what we’ve done against Ukraine in such a way as to allow them to reduce blunt, maybe our best form of influence there. We have to be very attuned to that When our instruments become duller over time, what does that mean in terms of shaping and influencing somebody else’s sovereign choices? And we need to be realistic about that. We can’t just sort of get back to we’ll just sanctions the heck out of them, and the problem will be resolved. I do think that we have to have a very clear understanding of the limits of our power, and I think we need to have both the disincentives and the incentives.

I mean, the strategic view is that you don’t want China to be some beleaguered country that feels like it has to act out in ways that are highly disruptive. The idea is that you want to bring China in to see that it can actually continue to use the international norms and laws to benefit its own country. In fact, its rise is greatly attributed to the very international system that it desires to change in certain ways. But how do you get them to have the epiphany that in fact, their standard of living, the stakes for the CCP, the leadership, the country are better when embedded as a responsible country in the international order than some kind of rogue maverick country outside of it?

That requires both carrots and sticks and a lot of swallowing our own pride and talking about different issues and having those discussions that lead us, I think to a better place. As it is right now, we’re kind of in this spiral of declining relations and friction that seems to be growing every week. We’ve got to figure out a way to course correct both countries and others to be able to get ourselves into a better place. So I do believe you’re right. If you only look at this problem of relationship between US and China as it’s a deterrence problem, you will fail every time to actually get the strategic outcome that we’re looking for.

Bryan Clark:

So Mike, to just follow up on that, so we need to leave open the potential for China to be able to grow economically, grow its influence and national power as long as it does so as a responsible player in the international system, because it seems like a lot of the rhetoric on the US side among elected officials tends to be containing, they don’t say containment, but they say basically, we got to keep China in its place. We have to prevent China from being able to get more influence around the world. And it seems like that’s a recipe for making China feel like they’re going to have to act out to get that influence.

Mike Studeman:

I mean, I do think that we need to responsibly put our efforts there, at the same time be keeping a weather eye on the fact that the way they’re thinking in Beijing right now has different objectives and different methods for achieving those objectives in mind. And many of them are Machiavellian. It’s the end justifies the means and not much has influenced them to change how they’re approaching things. And so I do think this is one of the most complex wicked problems that we face in the twenty-first century for a reason, and we can’t boil it down to just that simple thing about deterrence.

Bryan Clark:

Right, right. Which gets to the idea of a denial strategy is obviously going to be an inadequate approach

Mike Studeman:

Right, there’s an assurance strategy, that it has to involve China too as an object of assurance. That’s one additional element, and then the list goes on.

Dan Patt:

If I could just chime in briefly, yeah, right, I mean, a prevent defense is terrible, is a terrible play to just keep doing from the beginning of the game. That one section in our report, Bryan, talks about competition. And in a way you can think about this competition as it’s about the strength of bonds with allies, with other nations in the Pacific and across the world, and whether those are trade bonds or cultural bonds or military bonds, and the offense the US should be playing is largely about strengthening those, right? Building the denser, tighter network of allies and partners economically, culturally, militarily around a sense of values there. That has to be the model for winning the game in the longterm. And that model of competition doesn’t need China to disappear. It doesn’t need the CCP to collapse, right? That’s a competition that we can pursue with certainly the military, but beyond that, many instruments of US power.

Bryan Clark:

Go ahead.

Ezra Cohen:

Just one last thing, and I’ll say that there’s a lot of good talk about this now. I think what we’re talking about here, and there’s even talk from people at the Pentagon. They’ll go to a conference or something, they’ll say all these things that we’re saying, but then they go right back to their office and they sign another a hundred million dollars contract to support the denial strategy. And I just think that we really need to move off of this now, this idea that it’s just going to be denial, that it’s just going to be hard power deterrence that you’re talking about, but we need to see more than just words. There’s a lot of words now. There needs to actually be money decisions that are made.

Bryan Clark:

I have time for one more question I think, so in the back, sir.

Ken Scabe:

Hi, I’m Ken Scabe from Marubeni Corporation, a Japanese private company. So in terms of the safety net or hotline with China. So do you think that it’ll be operatable to build them through allied countries like Japan?

Mike Studeman:

Absolutely. I think that all countries, particularly ones that may have some contention related to disputes, whether it’s ones that are maritime or island based, an example here, the Senkakus, needs to ensure that they can call and clarify intentions and to be able to deescalate and not let one particular mistake that may have happened with a pilot or a mariner out there lead countries to then go down and exacerbate something that could have been controlled much earlier, how do you nip things in the bud because mistakes will be made. And I think that’s the great concern is that in Asia today, in the Indo-Pacific, there’s a lot of dry grass. And so the potential for one spark to get spreading much sooner is higher if you don’t have the ability to shower cold water on it. And that’s where the hotlines come into play, and multiple countries should have them if they don’t. But many actually already do have lines in with the Chinese, but particularly problematic right now between the US and China.

Bryan Clark:

Well, I think that’s a good place to end it. Is there anything else that you guys wanted to bring up before we stop? Well, thank you very much. So thanks all for being here. We appreciate your time. We appreciate your time online as well. So for Dan Pat, Ezra Cohen, and Admiral Mike Studeman, thank you for coming to the Hudson Institute and have a great day.

Mike Studeman:

Thanks.

Hudson will host Federal Communications Commissioner Olivia Trusty for an address on the national security importance of America’s communications infrastructure.

On January 20, Hudson Japan Chair Kenneth R. Weinstein will host Minister Yasutoshi Nishimura, former head of Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), for remarks on the Takaichi government’s economic security strategy.

Join Hudson for a conversation with Assistant Secretary of War for Industrial Base Policy Michael Cadenazzi, who leads the DoW’s efforts to develop and maintain the US defense industrial base to secure critical national security supply chains.

Join Hudson for a discussion with senior defense, industry, and policy leaders on how the US and Taiwan can advance collaborative models for codevelopment, coproduction, and supply chain integration.