The COVID pandemic and the rise of AI have something in common. Between them, they have upended one of the most consequential debates among American tech analysts, and largely refuted the claim that progress in America was coming to an end—that the Adams curve was flattening out as a Great Stagnation cooled the dynamism of American life.

The case for stagnation was a strong one. Current technologies, advocates warned, were providing diminishing returns, and productivity growth in American life was slowing. The regulatory burden on innovation in the United States inexorably grew. Compared with the optimism that accompanied earlier innovations like electricity, indoor plumbing, the internal combustion engine, antibiotics, refrigeration, and mass communications, Americans in the internet age seemed noticeably more risk averse and pessimistic about the future.

The stagnationists make some important points. But as my friend Tyler Cowen noted in his seminal 2011 book The Great Stagnation: How America Ate All the Low-Hanging Fruit of Modern History, Got Sick, and Will (Eventually) Feel Better, stagnation was never likely to be more than a pause. By 2020, Tyler saw the pause coming to an end as advances in medicine, battery technology, computing, and distance-working made themselves felt.

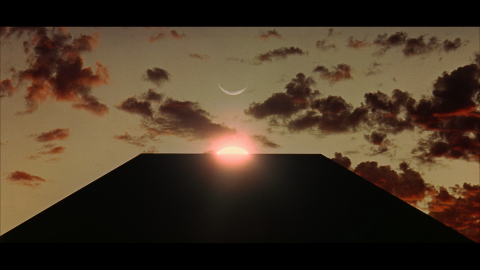

The alternation between a sense of stagnation and one of dizzyingly rapid change reflects, I think, the complexity of human society’s progression up the Adams curve. As a hiker begins to climb a mountain, it becomes harder to see the summit, and harder still to see—as the trail winds through forests and takes you up onto ridges and down into valleys—whether you are in fact making any progress. But along the way, there will be moments when you get a clear view of the summit looming above you and the immense distances you have already climbed, and those doubts will be stilled.

The advent of AI and the COVID pandemic provided two such moments of clarity. The swift appearance and rapid development of practical AI applications on a mass scale has surprised and alarmed many people close to the industry. Geoffrey Hinton, widely credited with developing the intellectual foundation for modern AI, resigned from Google last week to warn about the dangers of an invention so disruptive that he regrets helping to develop it. Hinton’s warning follows a letter signed by some well-regarded tech analysts and industry leaders ranging from Steve Wozniak to Elon Musk cautioning that the unchecked development of AI could pose a threat to the stability or even the survival of civilization as we know it.

The pandemic also showed us how far we have come. When COVID hit, and a panicked population looked for ways to stay safe, Americans discovered something that made this pandemic different from all others: The development of both the hardware and software in the enormous invisible realm we vaguely refer to as “the internet” had reached the point where the majority of the productive activities of American society could be conducted by tens of millions of people without leaving their homes.

But the impact of internet-empowered work from home (WFH) went far beyond helping us get past COVID. Without anybody really noticing, and with some of the world’s most acute observers lamenting the end of progress, the technological basis for a total transformation of the American workplace, urban landscape, and even family had quietly taken shape offstage. The characteristic workplace of the Industrial Revolution, the large, centralized workspace to which white-collar workers commute like clockwork five days a week, is no longer an economic necessity. The megacity of the Industrial Revolution, with an economically dominant central business district surrounded by rings of suburbs, is no longer a natural and inevitable form dictated by the nature of work. The potential for mass WFH also points toward a profound change in the nature of the family of the industrial era—when, uniquely in human history, most children and most parents in nonelite families spent most of their waking hours living separately from each other.

Productivity statistics, which essentially divide the value of a worker’s output by the amount of time spent on the job, do not capture these realities. Time spent at a desk is one thing, but the time spent commuting matters if we want to think more holistically. According to Census Bureau figures, the average commuter in the New York metro area spent roughly 75 minutes per day or 375 minutes per week commuting in 2019, the last year before the pandemic. During the pandemic, those workers produced essentially the same work without the commute, an efficiency gain of 15.6%. Factor in the reduced costs (gas, tolls, depreciation on cars, and bus and train fares), and it’s clear that the WFH model offers significant increases in the efficiency of work.

The ultimate impact on social productivity is likely to be higher still. The vast and cumbersome transit systems that the pre-internet economies required are costly to build and maintain. They contribute significantly to both public and private costs. If future economic growth can be unshackled from the need to endlessly expand these systems, so that cities and states do not have to invest such eyewatering sums in adding new lanes to existing freeways or building and operating new transit systems, a lot of money will be freed up. Similarly, workers will have fewer costs even as they enjoy more free time.

The big waves of change we call economic revolutions don’t just increase the amount of economic activity in a particular society. They change the nature of economic activity in ways that can be difficult to capture or understand. At the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, many economists shared the view of the physiocrats that agricultural production was the true basis of society and that all others were parasites. For them, agricultural productivity was the only kind that mattered. Industry, finance, and the service sector were irrelevant and unproductive. For these economists, developments like the early steam engines and spinning jennies were meaningless epiphenomena.

That would change. The Industrial Revolution would force shifts in economic theory and promote massive changes in the way economists measured and valued economic activity. Similarly, today as the economy develops and both the means of production and the objects of production mutate into radically new forms, we will have to develop new ideas about how the economy works and new measurements to tell us how well we are doing. Progress in the industrial era involved, among other things, developing new and faster ways to move commuters to and from the workplace. Progress in the information age may mean finding ways to help them achieve greater productivity without leaving their homes.

For all the talk of stagnation, the Adams curve remains a basic fact of contemporary life, and our society can expect new waves of both social and economic change as the 21st century proceeds. The best way to understand how that reality shapes our political and cultural environment is to step back from the present and look at the long view—at the role that technological and social development has played in the story of our kind. The picture that emerges is both promising and troubling.

The story of our species is full of surprises and plot twists, but just about as far back as we can explore the fossil record, the human family seems to be preoccupied with two principal fields of activity.

First, from the time of our remote ancestors to the present day, human beings have never stopped developing new tools and thinking up new ways to harness natural objects and forces to achieve human ends. Second, we’ve never ceased weaving thicker and more intricate webs of society, language, and culture. (The third thing we keep doing, having fights with other groups of humans, is, I think, best seen as a byproduct of our web-weaving activity.)

Whether measured by social or technical development, we’ve come a long way. Our culture and our technology are both unrecognizably complex compared to the achievements of our forebears. Our ancestors chipped flints on the savannah; today our telescopes scour remote galaxies for signs of the origins of the universe. We once lived in small family units and survived on what we hunted and gathered. Today we build vast cities and feast on exotic foods imported from all over the world.

Materialists like Karl Marx would say that technological progress drives cultural development. Idealists will tell you that it’s the culture and above all the ideas that drive events. To understand the arguments, think of the piano. Materialistically inclined musicologists argue that progress in the construction of new and more sonorous pianos allowed Ludwig van Beethoven to develop increasingly complex music. Their colleagues of a more idealistic or romantic bent would maintain that the unceasing demands by Beethoven and his contemporaries for better pianos to play the music they heard in their heads drove piano manufacturers to build instruments that kept the customers happy.

These chicken and egg controversies are hard to settle, but for my part, I’ve always thought Aristotle had the right approach. His definition of human beings as political animals points us to an understanding of human nature that integrates the “spiritual” and “material” elements of our lives into a seamless whole. As animals, we are grounded in the material world, but it is also part of our nature to engage with the world of abstractions and cultural meaning that go into our common existence. We are amphibians, intellectual and spiritual beings who spontaneously and naturally engage in logical reasoning, aesthetic creation, and moral discernment; and we are physical beings who live and act in the material world from which we draw our sustenance.

Whether you go with the materialists, the idealists, or us incarnationists, the outlines of the story are the same. As far back into the distant past as we can peer, human beings have been developing tools and techniques to impress their will on the natural environment, and they’ve been interacting with each other to create an ever-thicker web of social interaction and cultural meaning.

This may seem tediously obvious, but if there’s one thing I’ve learned over the decades, it’s the importance of interrogating the obvious. What could be more obvious and even humdrum than an apple falling from a tree? Many of the great discoveries and achievements come about because a determined person grabs hold of some apparently obvious phenomenon, demands to understand it and, like Jacob wrestling with the angel, says “I will not let you go until you bless me.”

There are three admittedly obvious things about the long story of human progress that I find indispensable when it comes to making sense of our times. The first is that while technological change and social and cultural change go hand in hand, they do not always move in the same direction or at the same pace—a fact that is particularly important when the pace of change is extremely rapid.

Living as we do in a time of rapid technological and social change, the gap between the world our institutions and cultural values took shape in and the conditions we live in today means that many of our most important institutions do not work very well. It is as if we were trying to run the software of the 2020s on computer hardware and operating systems from the 1990s.

Our political parties and institutions took shape long before the internet and social media existed. Our government bureaucracies, our schools, and our legal system were all built for conditions that no longer exist. Many of our labor market policies assume that people will work for one employer for most of their working lives.

Unfortunately, this is not just a matter of institutional hardware. Many of our political ideas and ideological assumptions also reflect the conditions of an earlier era. If society’s operating system is running on the equivalent of a long-outdated version of Windows, that makes real reform difficult to imagine, and harder still to carry out.

The bad news is that this creates a pervasive and self-reinforcing sense of alienation and frustration as people interact with many different institutions that are not fit for the purpose. The good news is that thinking clearly about these gaps and their causes can help us develop a reform agenda that can substantially improve the way America works—and those changes, because they make our institutions more efficient as well as more effective, will often save money rather than require greater spending.

The second feature of the story of human progress that matters today is that we happen to be caught up in one of the three great waves of change that most historians dignify with capital letters and associate with revolutions. The Neolithic, Industrial, and Information Revolutions all mark major milestones in the human story. The reality that we are now living through one of them is a fundamental feature of our time and one of the chief causes behind many of the problems and controversies we face.

Revolution is one of the most overused words in the political lexicon, but no lesser word adequately describes the scale, disruptiveness, and consequences of these three explosive events in the human story. The Neolithic Revolution, as the wave of changes connected to the development of settled agriculture is often called, was much more than a revolution in the ways people fed themselves. It was, literally, the dawn of history, as the first writing systems developed to handle the greater needs for permanent recordkeeping and commercial transaction under the new conditions. Those systems did not just enable the rise of bureaucracies and mercantile trade. Oral traditions were written down, forming the basis of organized religion. Scientific enquiries and philosophical debates could transcend the limits of space and time, as scholars could read the words of their predecessors.

The Neolithic Revolution was a time of explosive social change. The rise of cities and the elaborate political structures needed to govern them are just some of the consequences of the shift. Class systems developed along with increased specialization of labor as the relatively homogenous communities of previous eras gave way to a world of kings, nobles, priests, merchants, artisans, peasants, and slaves. Armies with professional soldiers appeared for the first time, along with wars of conquest.

The consequences of the Industrial Revolution were similarly far-reaching. At the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, cavalry officers still charged across battlefields sword in hand. The last great war of the industrial era concluded with the detonation of nuclear bombs. From the Enlightenment and the French Revolution to the rise of Marxism and the Russian and Chinese revolutions, the intellectual and political movements of the last 250 years have transformed the face of the world and led humanity on a series of adventures both magnificent and tragic.

The development of railroads, automobiles, and airplanes introduced changes in human culture and civilization that we still struggle to process. Unprecedented developments in mining, industry, and methods of energy generation and transmission have covered the Earth with the works of mankind. Urbanization, the rise of the industrial working class, the growth of nationalism, the development of mass public education, the cultural impact of mass entertainments like Hollywood movies: Each of these changes emerged from the all-conquering impact of the Industrial Revolution.

These are still early days, but the Information Revolution seems fated to be more dramatic still. A cascade of interlocking, interrelated social and technological change is driving global upheaval at an unprecedented speed. Before its work is done, the Information Revolution is likely to drive social, political, cultural, economic, and geopolitical transformations more sweeping and profound than anything the Industrial Revolution produced.

This is both a wonderful and a terrifying thing. On the one hand, humanity is becoming more productive and affluent than ever before. Already the average person with a cellphone has faster access to more information than anybody in the history of the world. New methods of research incorporating artificial intelligence have already accelerated the development of new treatments for disease, and the promise of these and similar technologies is only beginning to be fulfilled.

But that is not the whole story. New technologies enable government and corporate snooping on a scale that would have astounded (and delighted) Josef Stalin. Manufacturing and clerical jobs have been automated out of existence or outsourced to poor countries at rates that match the collapse of family farming in the 19th and 20th centuries. IT-enabled weapons and cyberattacks could make wars even deadlier and harder to avoid. Global and national financial systems, experiencing unprecedented rates of change and development as AI and other new technologies enable financial markets to achieve levels of complexity and velocity that the unaided human mind cannot comprehend, could experience devastating crises costing trillions of dollars and upending millions of lives.

Meanwhile, the Industrial Revolution continues across much of the world. Factories are still springing up in rice paddies across Asia; the first textile mills are popping up in some African countries. The massive migration to the cities across much of Africa and Asia continues even as the disruptions of the Information Revolution reverberate around the globe. The children of illiterate herdsmen scan social media on their cellphones. The world has never seen anything like this concatenation of explosive transformations, and the world that emerges from this era will be like nothing humanity has ever seen or dreamed.

This brings us to another feature of the ancient story of human progress that matters especially in our era: the tendency of human development to accelerate and intensify over time.

For thousands of years, the pace of humanity’s growing technological prowess and social complexity was almost unnoticeable over an individual lifespan. Archeologists can trace the spread of new techniques for chipping flints and making tools through prehistoric human society; historians and archeologists can work together to understand the spread of new metalworking techniques in the Bronze and Iron ages. But change was slow, and many people around the world never saw a tool or had an idea that would not have been familiar to their grandparents. And even when change happened, it was usually seen as an exceptional development, a stone falling into a pool that would, after the ripples died down, resume its previous and natural calm.

But over the last 700 years, the rate of human progress began perceptibly to pick up steam. Starting in Western Europe, the rate of technological and social change accelerated as a new kind of dynamism made itself felt. Windmills, double-entry bookkeeping, cannons, printing presses: World-changing inventions poured forth at an unprecedented rate.

This acceleration changed the way that history works. The Neolithic Revolution, associated with settled agriculture and the invention of writing, came thousands of years before the Industrial Revolution. The Industrial Revolution was only about two centuries old when the Information Revolution started to hit late in the 20th century. Increasingly, especially with advances in genetics and the science of the brain coming so quickly, it looks as if we are entering an age of permanent revolution in which radical technological and social changes cascade across the world largely nonstop. For people in our time, rapid and accelerating change is the norm; we hardly know anymore what stability feels like.

Much of the intellectual history of the last two centuries revolves around the efforts of great thinkers to wrap their heads around the Great Acceleration. The family of intellectual and political movements generally known as the Enlightenment grew out of the recognition of thinkers ranging from Voltaire to Goethe that something fundamental in the human condition had changed. Philosophers like Kant and Hegel were not just, like many of their predecessors, interested in unraveling the nature of existence. They found themselves drawn to the study of change. They were aware that the social and technological basis of European society was changing from decade to decade and even year to year. They wanted to understand what this meant, why it was happening, and what it portended for the future.

A heightened awareness of human progress and its impact on events led to the integration of philosophy and politics. “The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways. The point however is to change it.” Those words inscribed on Karl Marx’s tomb highlight the new sense of mission that impelled generations of thinkers to turn their understanding of the historical process into a concrete political program. Liberals and socialists developed competing programs to accelerate the process of progress and share its benefits more widely based on their understanding of the technological and sociological forces at work.

These debates still echo in politics today, but many 21st-century thinkers and activists have increasingly moved from a fascination with the fact of change to an alarmed analysis of the effects of its relentlessly accelerating rate. Change itself is old hat for us today. In 18th-century Europe, reflective people understood that the rate of historical change was significantly greater than in past times, and they were conscious of ongoing progress in technology and society as the unavoidable background of their own lives. In the 21st century, we don’t just feel the presence of progress. We feel the acceleration of progress as the Information Revolution unfolds. It is the consequences of that acceleration—both as we experience it today and as we extrapolate it into the future—that engage our attention and, increasingly, our concern.

Progress in small, measured doses is an exhilarating and energizing thing. But can there be too much of it? Can an individual or a society overdose on progress? Can the rate of social, economic, cultural, and technological change drive a particular society into a political, psychological, and moral spiral of crisis and dysfunction?

Judging from the history of the Industrial Revolution, the answer is yes. The Russian Revolution and the Nazi rise to power are only two examples of societies overwhelmed by the social and political stresses that rapid modernization brought. The Industrial Revolution and the international conflicts that accompanied it shook the foundations of social order around the world and produced a uniquely stressful international situation. Tested to the breaking point by the combination of the domestic and international consequences of the Industrial Revolution, Germany fell into one kind of abyss, Russia into another.

They were not alone. The multiethnic, multicultural states that characterized much of 18th- and 19th-century Europe disappeared in orgies of bloodletting as the Hapsburg, Romanov, and Ottoman empires dissolved. The collapse of Iran into the dismal fanaticism of the Islamic Republic, the serial disasters of Maoist China, genocides in Cambodia, Rwanda, and beyond: Each of these tragedies has its own distinct set of causes and consequences, but without the domestic and global upheavals associated with the Industrial Revolution and its numerous transformations of the human arena, it’s unlikely that any of these tragedies would have occurred.

The Anglo-American world was spared the worst of these upheavals, and after the horrors of World War II much of Western Europe and Japan seemed to have made their peace with the Industrial Revolution. During the long Cold War era, and with even more confidence after the fall of the Soviet Union, most people in these societies assumed that the political stability and social peace they had finally managed to build was a lasting and permanent achievement.

But is it? What if the Information Revolution, as seems likely, arrives faster, propagates more widely, hits harder, and digs deeper than the Industrial Revolution ever did?

As the rate of change increases globally, even the nimblest and most adaptable societies must struggle to adjust. The social and political unrest and dissatisfaction in the United States, leading some to fear an irretrievable breakdown in our political system, reflects America’s difficulties in coming to terms with the latest wave of tech-driven social and economic change.

America’s difficulties are not unique. Both democratic and authoritarian political systems around the world are facing new strains under the pressure of economic disruption, cultural conflict, and the corrosive impacts of social media.

The sense is widespread today, among elites as well as among the public at large, that the dogs of technological and economic change have slipped the leash: that things are happening to us faster than we can understand, much less control. “Things are in the saddle and ride mankind,” as Emerson wrote in the turmoil of the Industrial Revolution. Today, as I’ve written before, many feel that we don’t surf the web as much as the web surfs us.

Faced with the evident consequences of an accelerating rate of progress on an already-frayed social fabric, both intellectuals and activists have, since the early stages of the Industrial Revolution, looked for ways to slow, stop, or reverse the incoming tide. It didn’t work for King Canute, and it didn’t work for the 19th-century Luddites or the 20th-century Agrarians. Genies are not easily persuaded to return to their bottles. Progress is not going away, and change is not going to slow because humanity would like a mental health break.

The answer to the perils of progress cannot be less progress. As we’ve seen, the processes of technological and social development that we call progress are grounded in human nature itself. William Blake might have moaned about the “dark Satanic mills” overspreading the beautiful English countryside as the Industrial Revolution lurched into existence, but those mills could no more be stopped from proliferating than the sun can be stopped from rising.

Nor should those mills have been stopped. For all the evils of the Industrial Revolution, and for all the toxic social and environmental consequences we have inherited from it, both the material and social conditions of human life substantially improved because of it. Billions of people moved from illiteracy to fuller participation in the riches of human knowledge, from subordination to fuller participation in political and cultural life, from subsistence to affluence and from bondage to freedom. To cite a much higher authority, the blind saw, the deaf heard, the lame walked, and the poor had good news shared with them.

The Industrial Revolution was both soaring triumph and searing tragedy, glorious cultural and scientific achievement and unspeakable cruelty and crime. Far from being unique to that epoch, the mix of great good and great evil is what we see wherever we look in the long annals of our kind. The rise of the Roman Empire, the allied victory in World War II, the decolonization of Africa, and the history of the United States of America all combine these features of extraordinary accomplishment and shocking horror.

That is how we human beings roll. Our story of progress is not a made-for-children television special. History is rated X, not G, crammed to the bursting point with violence, injustice, foul language, nudity, and smoking. We’ve sailed on bloody seas to get to where we are, and the outlook is for more of the same. Trigger warnings should be posted in every delivery room. The world is not a safe space, and the arc of history is nobody’s poodle.

The way to cope with the onrushing waves of change and upheaval at home and abroad is to use the unprecedented financial, technological, cultural, and intellectual resources that progress creates to address the wrenchingly urgent and stupefyingly complex problems it inevitably brings. As a political movement the Luddites made nothing better for anyone. It was the wealth that the Industrial Revolution created, and the new forms of social and political organization that accompanied it, that allowed reformers to make the mills less dark and satanic over time.

If we are to surf the waves of change now rolling toward us instead of being overwhelmed by them, it will be because we have the wit, the wisdom, and the maturity to keep our psychological balance as we learn to bring the unprecedented resources of the Information Revolution effectively to bear on the unique demands of our time.

That would be a difficult task if the only challenge we faced came from the accelerating pace of change that defines our era. But there is one other complexity to consider. As the pace of change surges at an ever-increasing rate, the prospect of a fundamental change in the conditions of human existence looms larger from year to year. Will AI supersede humanity, leaving us inferior to the machines we have made? Will we upload our consciousness into cyberspace, perhaps downloading again into cloned designer bodies? Will we blow ourselves up in a nuclear holocaust or destroy ourselves in a series of climate catastrophes?

Apocalypse used to be a religious, even a mythological concept. But in our time, it is becoming a political possibility. The Silicon Valley tech lords speak of the Singularity even as some of them invest billions in longevity and consciousness research they hope will make them immortal. Climate activists warn of an imminent catastrophe even as the great powers rearm.

Progress has done many things for us, and few of us would exchange the dentistry, for example, of our time with that of even the recent past. But progress turns out to be paradoxical. Human ingenuity has made us much safer from natural calamities. We can treat many diseases, predict storms, build dams both to prevent floods and to save water against drought, and many other fine things. Many fewer of us starve than in former times, and billions of us today enjoy better living conditions than our forebears dreamed possible.

Yet if we are safer from most natural catastrophes, we are more vulnerable than ever to human-caused ones. Not only do we all live under the shadow of nuclear weapons and artificial general intelligence. We also live under the threat of financial catastrophe from the unanticipated convulsions of a banking system that few of us, and perhaps none of us, really understand. The impact of human industrial and agricultural activity on the natural environment threatens our future whether from climate change globally or the effects of air pollution in our hometowns. The social anomie characteristic of a decadent Blue Model society combined with the availability of cheap drugs contributes to more than 100,000 premature deaths in the United States each year. The 20th century saw stunning advances in medicine that saved millions of lives; millions more were lost in the fierce and unrelenting wars and repressions of that terrible time.

While the ever-accelerating and ascending wave of human progress has brought us to peaks of achievement and affluence that our ancestors could scarcely imagine, it has both failed to keep us safe from the most dangerous predators of all and—to the degree that the rate of progress has become a major force of destabilization—progress itself may now be the greatest source of danger humans face.

As I wrote in my last essay, we live in a singular century, and it is impossible to grasp either the psychology or the politics of our time without considering how this new reality affects a world that is already laboring under unprecedented stress.