Earlier this month, Senator Thom Tillis (R-NC) sent a letter to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) and to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), expressing concern about policymaking on drug patents and drug prices being driven by a narrative rooted more in policy goals than in actual data. He sent another letter to a policy organization, Initiative for Medicines, Access, and Knowledge (I-MAK), which has held itself out as go-to source for data on the number of patents covering drugs. I-MAK has become very popular; its drug patent numbers are invoked as fact by congresspersons, academics, congressional witnesses, and policy activists.

Senator Tillis is to be commended for expressing serious concerns about the unreliability of drug patent numbers repeatedly invoked in the policy debates over drug prices in Washington, D.C. His letter to the USPTO and FDA requests that the agencies engage in an “independent assessment and analysis of the sources and data that are being relied upon by those advocating for patent-based solutions to drug pricing.”

Senator Tillis’ letter to I-MAK similarly requests that it provide a “detailed explanation of your methodology for calculating the number of patents on a drug product that could be replicable by other researchers.” He also requests that I-MAK explain why its patent numbers covering drugs “differ so dramatically from public sources,” as well as explain why it claims in its reports that some patented drugs will retain market exclusivity for decades into the future when generic versions were already made available to patients in the healthcare market years ago.

Waiting for Answers

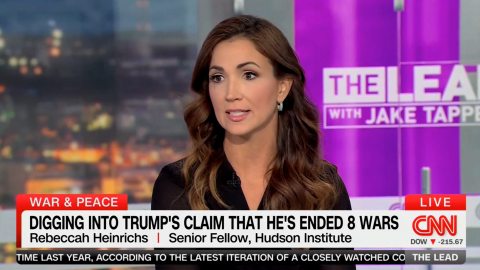

Many IP stakeholders are looking forward to seeing the responses from the USPTO, FDA, and I-MAK to Senator Tillis’ requests—especially me. Senator Tillis referenced in his letters my policy memo, Unreliable Data Have Infected the Policy Debates Over Drug (Hudson Institute, Jan. 19, 2022), and he discussed some of the examples I identified in my policy memo in which I found that the drug patent numbers asserted by I-MAK differed by orders of magnitude from the data available in official, public databases, such as patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book and in federal court opinions.

Senator Tillis also highlighted in his letters an analysis by Professor Chris Holman of a database created by Professor Robin Feldman at the Center for Innovation at UC-Hastings College of Law that makes claims about drug patent numbers raising similar concerns as I-MAK’s numbers. In his letters, for example, Senator Tillis notes that the UC-Hastings “Evergreen Drug Patent Search” database has entries for aspirin and suggests that aspirin still has exclusive protections against competition in the marketplace today. Yet, as Senator Tillis observes, “aspirin has been available in generic form for over 100 years.”

As I noted in my policy memo, policy debates over the property rights secured to drug innovators, as well as broader debates in healthcare policy about drug prices, should be based in reliable, publicly accessible data that is understandable to policymakers and whose methodology is replicable. This allows fact checking and, even more importantly, ensures proper “evidence-based policymaking, and not policy-based evidence-making” (an excellent phrase from Alan Marco, former Chief Economist at the USPTO, that I quote in my policy memo).

Return of the ‘Zombie Numbers’

I became interested in I-MAK’s drug patent numbers because the assertion of questionable, unverified numbers in patent policy debates is nothing new. Unreliable and unverifiable data have long infected patent policy debates.

More than a decade ago, the “patent troll” narrative was similarly driven by an unreliable and unverified claim that “patent trolls cost the U.S. economy $29 billion in 2011.” As I explained in a 2015 article, Repetition of Junk Science and Epithets Does Not Make Them True, this number was based in a private, secret database unavailable to scholars and policymakers for fact checking. This and other profound methodological problems with the study were repeatedly pointed out by many in op-eds and in conferences; it was thoroughly debunked by a rigorous critique by prominent academics applying standard empirical and statistical norms for research. This critique was published in 2014 in an academic journal. It was ignored in the D.C. policy debates that had built three years of arguments based on this allegedly factual claim.

As a result, the discredited $29 billion number continues to be resurrected again and again, as policy activists deem it useful to advance their agenda. A new policy organization, US Manufacturers Association for Development and Enterprise has burst onto the patent policy scene recently with extensive, targeted ads on social media platforms. It is pushing the invalid and unverified $29 billion number and directly linking to a decade-old report from the creators of the debunked study. In case US-MADE changes its website, here is the claim:

The careful and rigorous critique of this $29 billion number should have made something like this impossible, if evidence-based policymaking is the goal to which everyone aspires. At the very least, the assertion of the $29 billion number by policy activists and organizations pushing for new legislation or policies that weaken patent rights should be immediately suspect. Simply put, evidence-based policymaking does not seem to be the concern of US-MADE.

It seems that, no matter how many times the $29 billion number was proven invalid, it rises again to haunt the policy debates. These are zombie numbers—unreliable, unverified or discredited numbers that are pushed in the patent policy debates because they serve a preexisting policy goal. As happens in almost every movie or TV show about the zombie apocalypse, these zombie numbers should be laid to rest once and for all.

Noble Mission, Wrong Villain

To be sure, I-MAK is right about one thing in its work: We do need to overcome barriers to vaccination for COVID-19 and other viral and bacterial scourges. But I-MAK puts the blame in the wrong place. It’s a lot easier to criticize intellectual property than to address the actual causes of vaccine inequality—regulatory blockades, trade barriers, and even basic problems such as a lack of infrastructure for storing, transporting, and administering shots in developing countries. To address these pressing issues would be real, evidence-based policymaking in healthcare.

It was good to see Senator Tillis taking a stand for evidence-based policymaking on these important issues at the intersection of healthcare policy and patent policy. I hope his letters prompt the administration and other lawmakers to do the same.

In the past century, innovations in healthcare and biotech have made modern life a veritable miracle by any historical standard. These innovations are not guaranteed to continue if we don’t sustain the right policies that created them in the first place.

For this reason, we should be concerned about zombie numbers used by some organizations and activists to change patent laws or to push for sweeping antitrust actions against innovators. This is especially the case when legislation or agency enforcement actions are overinclusive and hurt all innovators. In patent law as in healthcare policy, the maxim is the same: First, do no harm.

Read in IPWatchdog