It is not just material power that matters in international politics but how cleverly one wields it compared with other nations. The People’s Liberation Army has not fought a war since 1979, when Vietnamese forces more than held their own against the Chinese invaders.

Since then, China has been working out ways to win without fighting.

The PLA is increasingly present and active in the Taiwan Straits and the East and South China seas. It has a military base in Djibouti which is strategically located on the Horn of Africa. In recent weeks, it has taken significant steps towards getting a de facto one in Solomon Islands.

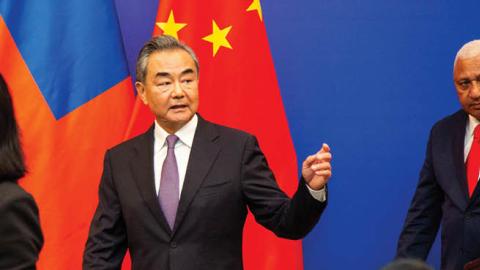

This brings us to Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s current visit to the Pacific. While we have known for some time that China wants a military stronghold in the Pacific, this trip is indicative of increasing ambition, daring and confidence.

It is also evidence of Chinese impatience and arrogance. Wang will return home with a handful of signatures. But Beijing will have overplayed its hand by abandoning its previous patient approach and creating the conditions for plausible deniability of its real objectives. It has been forced to at least delay its sweeping proposed ten nation security agreement for the time being, after meeting disagreement from some governments in the consensus-minded region.

Think about how China has advanced its efforts to undermine the interests of other great powers while meeting minimal, or else only disorganised, resistance.

For example, when ramping up its military modernisation efforts in the early 2000s, Beijing promised its purpose was simply to dissuade Taiwan from unilaterally declaring independence rather than force Taiwan into submission.

Moreover, we were told those modernisation efforts had nothing to do with acquiring the means to enforce Chinese claims on the Japanese-owned Senkaku Islands or to virtually the entire South China Sea.

Part of the trick was to not only convince others about the modesty of its objectives but to move forward gradually such that one might explain away or ignore each advancing Chinese step on the basis that it was not a game-changer.

After the announcement of the wide-ranging security deal with China in April, Solomons Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare dismissed Australian and allied concerns as those countries “sowing instability” and “nonsense”, while affirming that the Solomons had no intention of joining any geopolitical contest.

Beijing characterised the procession of Australian and American political leaders and officials coming through the Solomons to dissuade the latter from signing the security deal with China as patronising and motivated by paranoia.

Wang’s arrival undermines all that, as it is indisputable confirmation of Chinese ambition and Sogavare’s disingenuousness.

Putting Pacific Leaders on the Spot

Moreover, his high-profile visit puts the Pacific nations on the spot as their leaders can no longer act as if they were unaware of what they are getting their nations into when signing on the dotted line.

Some are still putting pen to paper on deals covering a range of issues. But their personal and political motivations in doing so will be more closely examined. To hold on to power, they will need to justify giving Beijing direct influence over domestic security, industry, or surveillance of populations.

And if there is a creeping Chinese military and security presence, as is probable, Pacific leaders will have to explain to angry and anxious populations why they are prepared to conclude agreements with irreversible strategic and security consequences.

They will be asked why they are dragging their small nations into the epicentre of Indo-Pacific geopolitics and competition and moving ever closer to China, which has multiple disputes with other countries and is undertaking the most rapid expansion of defence forces in peacetime history.

Silver Lining

Troubling as current events are, there is a silver lining in that any lingering or residual strategic complacency in Canberra or elsewhere will have dissipated.

But Chinese hubris will not become overreach without Australia and others seizing the initiative. It is not enough to remain comfortable in the knowledge that our people-to-people links with many island nations are better, or we are the preferred partner of choice for many Pacific Island countries.

In and of itself, our past and present good works will not permanently forestall a Chinese security presence in the Pacific. That being the case, and if increased securitisation or even militarisation is inevitable, it is better to accept the reality of the new environment and ensure it unfolds in ways that suit our interests and those of reliable Pacific partners, rather than China’s.

Instead of urging countries not to sign agreements with China, we need to offer them an alternative.

For example, Australia already has a Pacific Maritime Security Program. This is a $2 billion program over several decades to help Pacific Island states monitor and protect their vast exclusive economic zones, including delivery of 21 Guardian class patrol boats by 2023. There will be calls to spend and do more.

However, it is not necessarily a matter of simply outspending China. Helping these countries to secure their EEZs can be better aligned with economic and development goals of assisting them with the responsible and sustainable exploitation of the ocean economy in ways which create well-paid jobs and benefit local populations.

Advanced democracies are better at this than China. This means more complete packages with financial, infrastructure, technological, and upskilling aspects to it in addition to the maritime security elements. This could be done in closer coordination with the United States, Japan, and New Zealand.

And if we can work with local military or police forces from several Pacific Island nations to set up and contribute to a more effective and accountable rapid response force with, then we should do so. Others on the ground will have many more ideas.

The broader point is for Australia and its allies to immediately prioritise those Pacific states with whom we can forge deeper security and economic relations.

The more transparent and equal Australian and allied arrangements will be in stark contrast to the unequal and opaque Chinese alternative. It does not mean giving up or abandoning those island nations leaning towards China. But we do need to move ahead with those leaders who genuinely want better and fairer agreements for their people and the region.

And if Sogavare or others persist in accepting Chinese offerings, let them become the pariahs and outliers in the Pacific Island community.

Read in Australian Financial Review