For the last several days, State Department spokesperson Marie Harf has been at pains to explain why Iran is not violating the interim nuclear agreement, or Joint Plan of Action. For the last few days, the Obama administration has been pushing back against a New York Times article published Monday that quoted an IAEA report documenting how Iran’s “stockpile of nuclear fuel increased about 20 percent over the last 18 months.”

The administration understands the story is damaging. If Iran is cheating now with sanctions still in place, then it is only logical to assume the Iranians will cheat when sanctions are relieved under the terms of the final deal. However, by campaigning against the Times piece—on Twitter feeds, like Harf’s and that of Obama aide Ben Rhodes, in several press conferences, and through former negotiators —all the Obama White House has done is underscore its vulnerability.

In Wednesday’s press conference at the State Department, Harf punted. __"We can talk about what [Iran is] going to do [until the June 30 deadline for the final deal] ... [b]ut if we can get a comprehensive joint plan of action, they're going to take that stockpile and reduce it hugely down."__

__In other words, let’s not focus so much on the interim deal because the big game is the final agreement, which will resolve the stockpile issue once and for all, as well as any other concerns.__ Maybe it’s a reasonable response from a policy perspective—e.g., the JPOA was just a bridge to get to the JCPOA—but it also highlights how poorly the Obama administration has managed negotiations with the clerical regime in Tehran. Instead of holding Iran to its part of the bargain, the White House makes excuses when Iran cheats—and beats up on U.S. journalists and the U.N. agency that is responsible for monitoring Iran’s nuclear program.

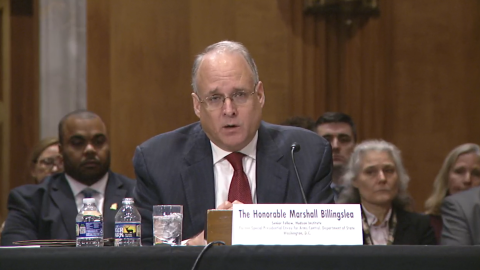

Some former State Department officials are not impressed with the administration’s diplomatic maneuvers. “The administration's argument that there is no alternative to approving an agreement is incorrect, and tantamount to advocating an ‘any agreement is better than none’ position,” former U.S. ambassador James Jeffrey said Wednesday. An experienced Middle East hand who served as American envoy to Iraq and Turkey, and now a fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Jeffrey spoke in front of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to urge Congress to consider several key points in reviewing any prospective deal with Tehran.

Among others, Jeffrey noted that “the agreement cannot be considered outside the context of Iran's record of destabilization in the region.” He continued: “Either an Iranian nuclear weapons capability, or an Iran politically empowered by an agreement that stops it just short of such a capability, would pose extraordinary new threats to a region already under stress, and undermine the above U.S. vital interests.”

Consequently, Jeffrey explained, if Tehran’s path to the bomb isn’t stopped through an agreement, the United States must be ready “to use force if Iran approaches a nuclear weapons capability.” The former ambassador acknowledges that “a military confrontation with Iran could be costly and risk escalation, but, absent spectacularly bad U.S. decisions, it is unlikely to produce either a U.S. defeat or a ‘war’ in the sense normally used in American political debate -- endless, bloody ground combat by hundreds of thousands of troops as in Iraq or Vietnam. Based my experience I know how uncertain any resort to force is, but all our security interests are ultimately anchored on willingness to use force, and success doing so.”

Even with an agreement, Jeffrey argued, “the ultimate restraint on Iran reaching a nuclear weapons capability resides as well in the capability and intent of the U.S. to stop Iran militarily from reaching a nuclear weapons capability.” Accordingly, Jeffrey recommended that Congress “support such a deterrence policy by passing in one or another form an advance authorization for the use of military force against an Iran in breakout.”

The administration for its part should make clear what its redline is for military action against Iran—what Iranian steps or situation would be considered a "threshold" requiring the U.S. to act on its "prevent a nuclear-armed Iran" policy. Clarity on congressional and thus American public support for military action, and clarity on when that action would be taken, would go far to refurbish American deterrence and make it less likely that we would be tested.

That’s clarity indeed. However, as we’ve seen illustrated this week by the Obama administration’s efforts to obscure Iran’s cheating, clarity is a virtue the White House seems not to prize.