In its proposed FY2023 National Defense Authorization Act, the Senate Armed Services Committee threw a funding lifeline to the Navy’s Snakehead Large Diameter Unmanned Undersea Vehicle, or LDUUV, after the service had zeroed out the program due to its unwieldy deployment scheme and slow development.

The Navy’s decision was premature. Future offensive undersea operations will depend on vehicles like Snakehead with substantial endurance, depth and payload. And its shortfalls could be addressed by not treating it and other unmanned systems extensions of submarines, but instead as teammates that could be deployed from air, surface ships or shore.

Long considered the US military’s asymmetric advantage, US attack submarines face an increasingly contested environment undersea. China and Russia are deploying passive sonar systems like the Cold War Sound Surveillance System, or SOSUS, arrays on the sea floor across the South and East China Seas or Barents Sea, respectively. US submarines are the world’s quietest, but if they deploy vehicles or shoot weapons in these waters, they could quickly be detected and attacked by missile or aircraft-deployed torpedoes. Regardless of whether the attacks are ultimately successful, they would force US submarines to immediately break off operations and evade.

Even if they remain quiet, US submarines will likely have to contend with mines and bottom-mounted active sonars that could guard the approaches to militarily important areas for China and Russia, such as the Taiwan Strait. Although these systems have threatened submarines since World War I, the newest generations are much more capable and can be deployed well in advance of hostilities, remaining dormant for months or years until needed.

Retaining America’s undersea edge will require US submariners to employ techniques developed by aviators to overcome air defense systems. Bombers and fighters depend on electronic warfare aircraft to suppress air defenses by jamming radars and radios or destroying enemy systems with anti-radiation missiles. Similarly, submarines making their way into enemy waters will need unmanned vehicle escorts to counter the sensors and weapons China and Russia are deploying undersea.

The Navy’s medium UUVs are its most mature class of vehicle and include the Mk-18s long used for minehunting and bottom mapping. But MUUVs launched from shore may lack the endurance to conduct sustained acoustic jamming, act as decoys, or find and attack sonar arrays and mines. Carrying MUUVs on the protected submarine would take up valuable torpedo stows, although recoverable vehicles like the Navy’s planned Razorback MUUV could make the trade worthwhile for avoiding enemy mines.

Small UUVs like the new Lionfish could be deployed from submarine countermeasure launchers to act as acoustic jammers or decoys, like today’s Expendable Mobile Anti-Submarine Warfare Training Target, without impacting the submarine’s weapon payload. Lionfish could also attack sensor arrays on the sea floor using explosive charges. And while they would not take up a torpedo stow, Lionfish could be deployed by the Navy’s Orca extra-large UUV to reduce the submarine’s risk of counter-detection from operating the countermeasure launcher.

But acoustic jammers and seabed weapons, especially small ones like Lionfish, will need proximity to enemy sensors, cables or mines to be effective, which points to a significant gap in the Navy’s undersea portfolio. During peacetime, MUUVs deployed by surface ships could survey and map adversary undersea defenses, but their endurance limits will require the host vessel to remain nearby, which would alert opponents of the survey operation. And submarines that could conduct surveys covertly have other intelligence-gathering, anti-submarine warfare, or training missions to complete.

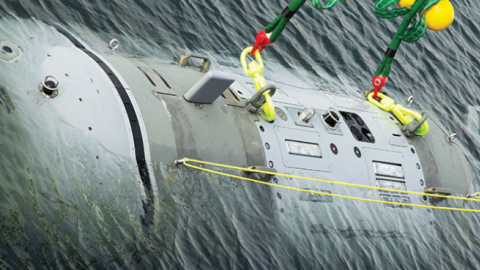

With its intended multi-day endurance, Snakehead could provide the pre-conflict intelligence needed to enable suppression or destruction of undersea defenses – but only if they’re used more creatively. Launched from a dry-deck shelter on the back of an attack submarine, Snakehead was intended to extend the submarine’s surveillance reach and persistence. This deployment scheme ties up shelters that are in high demand by special forces and largely prevents the host submarine from conducting other operations.

Rather, using funding proposed by the Senate, the Navy could revise Snakehead’s deployment scheme to launch it from other vessels such as amphibious ships, whose well decks would allow LDUUVs to swim out of a simple cradle rather than rely on a complicated mechanism to leave and reenter the dry deck shelter.

Snakehead could similarly be deployed from shore by Marine Stand-In Forces at Expeditionary Advance Bases. These alternatives would address one of the Navy’s main concerns about the program, as well as enable speeding up testing by decoupling LDUUV development from host submarine availability.

The Navy’s undersea forces are coming to grips with the need to fight their way into enemy waters. Learning from aviation history, submariners could use unmanned vehicles to defeat the undersea defenses opponents like China and Russia are establishing to protect their future aggression. The Navy needs to align its UUV portfolio around these missions or risk losing its longstanding undersea advantage.

Read in Breaking Defense