Experts say we are only at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, and that the United States and other large, complex societies have a long way to go before they can return to their level of activity before “Zoom-bombing” and “social distancing” entered the lexicon. It is increasingly clear, however, that DoD leaders in a post-pandemic fiscal environment will be under pressure to wring the best defense they can from tighter military budgets as economic recovery and debt servicing crowd out discretionary government spending.

With troops returning home from the Middle East, Congress and the next Presidential Administration may be tempted to redirect defense funding to other domestic needs, similar to the 1990s “ peace dividend ” harvested following the Cold War. Those savings were enabled in large part by reductions under the “ Base Force ” concept championed by Joint Chiefs Chairman GEN Colin Powell, which shrank U.S. military forces by about a quarter.

Flat post-pandemic defense budgets are unlikely to cut the U.S. military as much as the Base Force, but they will prevent DoD from buying new gear before retiring some of its existing hardware. The situation is not dissimilar to the 1990s when funding constraints and the availability of new technologies prompted defense leaders to pursue a transformational agenda that would replace the analog Cold War military with a digital-age force.

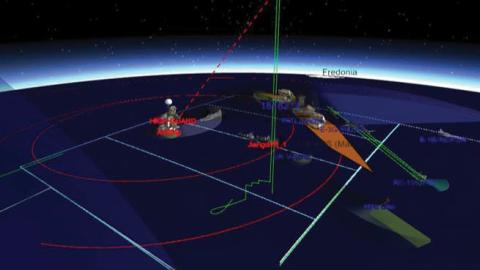

In the net-centric military envisioned by many leading Pentagon thinkers, a high-performance information grid and ubiquitous sensing with enforced compliance to standards would allow commanders to optimize operations over wide areas. By efficiently using forces and weapons, the smaller 21st Century U.S. military would punch well above its weight or that of the Cold War force it replaced.

Elements of the net-centric military did emerge, along with some of the efficiencies its promoters predicted. But it has only been tested in benign environments against third-tier militaries. Against Chinese or Russian forces, it is unlikely the brittle network infrastructure cobbled together to win wars in the Middle East will hold up, denying commanders their "God's Eye View" and ability to direct the actions of every unit in the theater.

The fog of war will endure

In the potential post-pandemic budget crunch, we risk going down the same road with Joint All-Domain Command and Control, or JADC2, and Artificial Intelligence, or AI. Many defense leaders view JADC2 as a unifying network that will connect forces from all domains across a theater. Advocates argue the combination of JADC2 with AI could enable commanders to cut through the normal fog of war by gaining pervasive situational awareness, predicting adversary actions, and rapidly building and enacting plans for their own operations.

Although AI-enabled systems are often characterized as prediction machines, they generally need either large amounts of analogous historical data or expert assessments to predict the likely outcome from a set of conditions and actions.

While historical results are easy to obtain for weather forecasts, chess matches, or automobile traffic, each military conflict occurs in a unique context, defying efforts to build a comparable set of training data. And although experts in Chinese or Russian military tactics and capabilities could attempt to train an AI-enabled analysis engine for JADC2, war is an intrinsically complex, incorporating innumerable known and unknown human interactions between the combatants and their environment, including the civilian population.

Most challenging to the prediction of combat actions and outcomes is the interaction of military forces with each other. As opposing units attempt to achieve their objectives while denying the adversary's, new and unexpected behaviors emerge that could not have been predicted by simply assessing one force in isolation or one force against a single predicted enemy course of action. Even if an AI-enabled C2 system can understand how the behavior of individual units or formations work, it cannot predict the behavior of the whole. Despite all the advances of Silicon Valley, using AI to predict warfare outcomes remains as fraught as when DARPA lasted tried to develop a “ crystal ball. "

The challenges of prediction are compounded by the expectation of JADC2 proponents that it will connect all the units in a theater nearly continuously. Although improving interoperability is a worthy and necessary goal, achieving ubiquitous, wide-area communications connectivity–also the objective of Net-Centric Warfare–is a distraction from the need for commanders to embrace the complexity of warfare and creatively employ the forces under their command.

Embracing complexity and creativity

Beyond eliminating war’s fog and friction, Net-Centric Warfare promised efficiency and optimization to make the most of a smaller U.S. military. Some JADC2 advocates argue it could offer similar benefits. However, warfare’s inherent complexity, environmental factors, and adversary jamming and deception will undoubtedly prevent JADC2 from enabling the smaller post-pandemic U.S. military from punching with the weight of today’s force.

But there is an alternative approach to making the most out of dwindling resources, and that is to embrace complexity and emergent behavior, rather than try to eliminate it.

Instead of trying to optimize the military to compensate for capacity reductions, JADC2 and similar command and control systems should focus on enabling commanders to creatively employ their forces and fight in new and unexpected ways. A commander executing mission command can adapt to changing circumstances and adversary actions while imposing complexity and uncertainty on an enemy. Without effective command and control tools, leaders disconnected from senior commanders due to adversary communication jamming may be unable to fully exploit the growing collection of unmanned and remote systems under their command. That should be the goal of JADC2.

Read in RealClear Defense