China’s leader Xi Jinping wants to integrate Taiwan into the mainland during his lifetime. He has instructed his military to be ready to fight and win a war over Taiwan in this decade. Anthony Albanese’s government seems determined not to talk about the possibility of conflict for the sake of stabilising relations with China.

But the assessment made during the Scott Morrison era that this decade is the critical and dangerous one has not been repudiated by Albanese. Which means that deterring China from using force against Taiwan remains the important and urgent task.

How do we collectively deter China from using force against Taiwan? Up to now, the United States and allies such as Australia rely on convincing China that it is not likely to achieve its military, and ultimately political, objectives using force against Taiwan. This is known as deterrence by denial.

Even so, we are failing to deter China from committing increasingly frequent acts of aggression and intimidation against Taiwan in the grey zone that is aggressive actions that are not yet sufficient to warrant a direct military retaliatory response. In 2023 alone, there were more than 1100 People’s Liberation Army incursions into Taiwanese maritime and airspace.

Allowing China free rein in this so-called grey zone is dangerous. Indeed, the bolder China becomes in the grey zone, the more likely it is that deterring China from launching an invasion against Taiwan will eventually fail. This means that we must consider imposing non-military costs against China every time it coerces and intimidates Taiwan. The question is how to impose costs against China effectively without triggering an unintended conflict.

Danger of retreat behind red lines

If Chinese aggressive actions in the grey zone are defined as those that do not warrant a kinetic and martial response, why be concerned about Chinese incursions and other forms of PLA intimidation? Because successful deterrence needs to be understood in a dynamic rather than static sense.

A static sense of deterrence is based on the idea that red lines are issued to China, in this context: ‘Do Not Invade Taiwan’. The PLA crossing the red line will not be a successful action and China will suffer unacceptable costs if it does so. The problem is that this static notion of deterrence does not align with empirical reality when it comes to the psychology and practice of how violence and wars begin. Aggressors tend to push boundaries to gauge resolve and responses before forming a view that escalation and the use of kinetic violence will be beneficial.

China’s salami slicing approach to using PLA forces to normalise creeping aggression against Taiwan is a classic example of why a static approach to deterrence will probably fail. With each instance of aggressive intent or incursion not responded to, China creeps ever closer to crossing the red line of attacking Taiwan. This is because with each unpunished advance, Beijing forms the view that Taiwan or its allies are likely to lack the resolve or preparedness to bear the risk or cost of responding to any Chinese action. At the same time, practice makes perfect. The PLA becomes better positioned and more skilled in tactical and operational terms. With each unpunished action, Beijing begins to doubt whether the US and its allies are really prepared to impose unacceptable pain and punishment against China if an invasion begins.

This means that deterrence cannot only be about signalling to China what might happen if Beijing decides to invade Taiwan. There needs to be constant signalling to China using a schedule of responses as Chinese acts of coercion or incursion occur. And if Beijing initially ignores these signals, then we need to carry through with planned responses of punishment. In other words, and against the losing mindset of always calling for calm, escalation needs to be seen as an essential element in the toolkit of deterrence rather than a failure of diplomacy. Just as China seeks to condition us to accept and internalise Chinese aggression, we need to condition China to internalise the reality that it will bear increasing costs if it continues to coerce Taiwan, making the threat more credible that it will suffer unacceptable pain should it cross that redline.

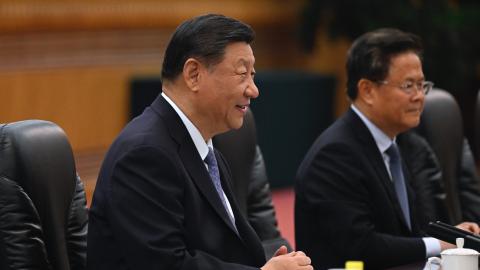

Deterring Xi

Xi’s authority and control over all relevant aspects of Chinese decision making, including military and foreign policy, is unchallenged; deterring China means deterring Xi.

How then to change Xi’s mind? Many observers of China argue that performance-based legitimacy is the only basis on which the regime can retain the support of citizens. The modern twist to this is that it is the standing and legitimacy of Xi, which is all important. For example, once Xi set the objective of achieving zero-COVID-19, that became the sole yardstick of his personal performance-based legitimacy filtering down through the governance system. From early 2020 to the end of 2022, the CCP government abandoned many hitherto critical elements of performance-based legitimacy, such as economic growth and material advancement for the people, in favour of zero-COVID-19.

The sudden about-turn in December 2022 to end lockdowns is revealing. The protests in multiple cities and in many universities in late 2022 were unusual in that participants openly called for Xi to step down. These protests occurring alongside leaders of powerful state-owned-enterprises and national champions becoming increasingly dissatisfied with restrictions on economic activity. These complaints were the most substantive challenge to a Chinese leader since the 1989 protests.

The point is that direct threats to Xi’s standing, his personal legitimacy, and the credibility of his personal vision and goals for the country appear more important to Xi than objective assessments and impacts on China’s comprehensive national power or even the CCP’s domestic reputation.

Once Xi’s personal directives and objectives are set, he seems more prepared to absorb international criticism and opprobrium than previous leaders. It was only when policies championed by Xi began to fail that he changed course as the personal and political risk for him deepened. In this sense, Xi is much more self-referential than his predecessors regarding the matters and issues he prioritises.

On the economy more generally, Xi’s security-first approach to economics and his prioritisation of personal control and dominance over most aspects of economic decision-making and corporate activity are different in nature and scale to predecessors. A slowing economy per se is unlikely to impose decisive restrictions on Xi over the rest of this decade as he pursues his security and geopolitical goals. His foremost objective is not to overtake the US as the largest economy (even if that is desirable for him) or even to help China avoid the so-called middle-income trap but to extend his personal control and dominance over the political economy, enhancing his ability to use all the tools of national power.

Changing Xi’s calculations must involve threatening his control and dominance over a political economy that he is reorganising to serve national security objectives as he defines them. Xi only changes his mind if his personal performance legitimacy or control is under threat. And once he changes his calculation and therefore his mind, he tends to do so quickly and decisively without regard for consequences, with no regret or embarrassment, and with minimal concern about international criticism unless such criticism directly undermines him.

Deterring attack on Taiwan

For the purposes of deterrence, non-military costs need to be imposed in ways that matter to Xi each time China engages in coercive or aggressive activities against Taiwan. It can only be led by the US but should be supported by any ally serious about preventing a war over Taiwan.

Just as Beijing currently benefits from a situation where other countries have normalised and internalised Chinese coercion and aggression, China needs to accept that a US and allied retaliatory non-military response is likely to occur every time Xi creeps closer to the red line. Each tit-for-tat cost imposed on China every time it intimidates Taiwan must incrementally add to the accumulated damage it does to Xi’s personal political, economic, and diplomatic plans and objectives.

The key is to construct a hierarchy of Xi’s priorities and vulnerabilities as he perceives them for the purposes of populating an escalatory ladder of non-military cost imposition based on how much anxiety certain measures will cause Xi and the Chinese leadership. These include actions against Chinese tech companies essential to advancing Xi’s flagship plans such as Made in China 2025 and Dual Circulation Policy.

Deterrence is a constant game of ‘chicken’ and getting the other side to blink. In technical jargon, deterrence by cost imposition is about increasing the other side’s cost burden each time they act against our interests.

Xi is preparing China for war and makes no secret about it. To change this terrible trajectory, we need to find non-military ways to cause Xi to blink and do so regularly. Being able to do so means we have a better chance of changing Xi’s calculations and risk assessments to our advantage and keeping the peace in the Taiwan Straits.