At first, the speaker solemnly recounted, the invading aircraft dropped tear gas bombs but the “soldiers learned to scatter, waiting until the wind had rapidly dispersed the poisonous gas.”

Adjusting their tactics, the aircraft then dropped barrels of mustard gas. The barrels would rupture upon impact, but the poisonous effect was limited. So, for more efficient delivery, “Special sprayers were installed on board aircraft so that they could vaporize, over vast areas of territory, a fine, death-dealing rain.”

Groups of aircraft formed in long trails so the “fog issuing from them formed a continuous sheet.” The aircraft, on orders from higher command, made multiple passes so that “soldiers, women, children, cattle, rivers, lakes, and pastures were drenched continually with this deadly rain.”

This, the speaker charged, was the invading army’s chief method of warfare: “to scatter fear and death” and “to kill off systematically all living creatures” and carry “ravage and terror into the most densely populated parts of the territory.”

In all tens of thousands of victims succumbed to this ghastly dew: “The deadly rain that fell from the aircraft made all those whom it touched fly shrieking in pain. All those who drank the poisoned water or ate infected food also succumbed in dreadful suffering.”

These words set the predicate for one of the most prescient, eloquent, and oft-forgotten rhetorical speeches of the 20th century.

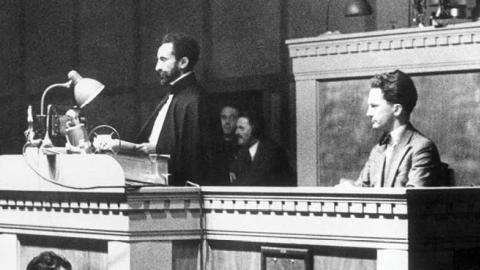

And so, it was in June of 1936 when emperor Haile Selassie, in his appeal to the League of Nations, denounced the aggression inflicted on the Ethiopian people by Benito Mussolini’s army. For months, similar appeals made by Ethiopian delegates had gone unanswered.

“That is why,” the emperor intoned, “I decided to come myself to bear witness against the crime perpetrated against my people and give Europe a warning of the doom that awaits it, if it should bow before the accomplished fact.”

The doom that awaits it. It’s difficult to cull from modern history a more prophetic pleading made before an international body — especially one conceived to prevent small nations being tortured and swallowed-up by large nations. Let alone a pleading that presaged by a few years the most destructive calamity in human history.

After all, the interwar years (1919-38) had been characterized by wholesale naval disarmament and an international treaty outlawing war. So why, the prevailing collective security theory posits, would small nations have anything to worry about? Certainly, the League would rise to the occasion and stop Mussolini’s madness.

But Selassie knew better. Already Imperial Japan had invaded Manchuria and by 1937 occupied large swaths of China. And growing accusations of Japanese atrocities and war crimes were seeping into the western press. The widening arc of fascism did not bode well for Ethiopia.

Selassie harbored no illusions. The excruciating failure of collective security was apparent. He knew help was not on the way. And he knew darkness was coming to Europe.

So, in that context, perhaps Selassie was creating an historical record, a template for what not to do in the coming post-calamity world.

He exposed Mussolini’s duplicity in signing treaties of friendship with security guarantees all the while secretly and deliberately preparing for Ethiopia’s conquest.

He called-out the inadequacy of sanctions: “At no time, and under no circumstances could sanctions that were intentionally inadequate, intentionally badly applied, stop an aggressor. This is not a case of the impossibility of stopping an aggressor but of refusal to stop an aggressor.”

And with war thrust upon him, Selassie declared “I did not wish for war, that it was imposed upon me … and in that struggle I was the defender of the cause of all small States exposed to the greed of a powerful neighbor.”

Today we once again live in a world of small states living in proximity to powerfully revanchist neighbors. And once again we hear statesman invoking perhaps the most discredited foreign policy axiom in modern times: equipping small states to defend themselves provokes aggression.

Selassie, in admitting his most lethal mistake, admonished the assembled delegates with a warning for the ages. “Despite the inferiority of my weapons,” he lamented, “my confidence in the League was absolute. I thought it to be impossible that fifty-two nations … should be successfully opposed by a single aggressor. Counting on the faith due to treaties, I had made no preparation for war, and that is the case with certain small countries in Europe.”

His peroration hung like a pall over the assembled delegates:

Invoking Great Power promises of collective security to small states “on whom weighs the threat that they may one day suffer the fate of Ethiopia,” Selassie concluded: “I ask what measures do you intend to take? What reply shall I take back to my people?”

Unanswered questions then. But good questions to ask today.

Read in The American Spectator