Supreme Allied Commanders on the Past, Present, and Future of NATO

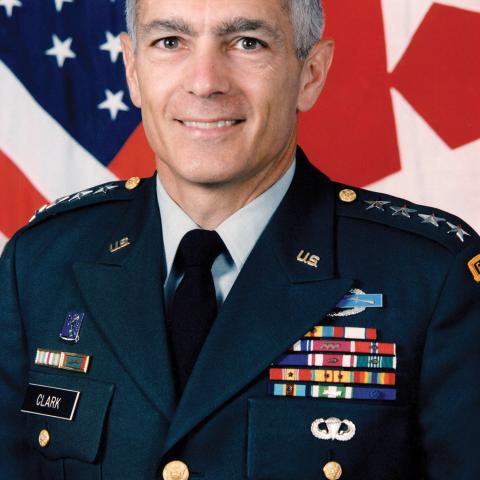

Supreme Allied Commander Europe, 1997–2000

Supreme Allied Commander Europe, 2013–2016

Supreme Allied Commander Europe, 2016–2019

Supreme Allied Commander Europe, 2019–2022

Senior Fellow and Director, Center on Europe and Eurasia

Peter Rough is a senior fellow and director of the Center on Europe and Eurasia at Hudson Institute.

On July 10, President Joe Biden will gather fellow North Atlantic Treaty Organization leaders in Washington to celebrate 75 years of the alliance and chart a direction for the way ahead. Over the course of NATO’s existence, warfare has changed in dramatic ways, punctuated by offset strategies and revolutions in military affairs. Today, the large-scale war in Ukraine is spawning battlefield innovations, which the alliance is attempting to process and understand.

To discuss the evolution of NATO warfighting capabilities and the state of the alliance, please join NATO Public Forum think tank consortium members Hudson Institute, the Center for a New American Security (CNAS), the Atlantic Council, the German Marshall Fund of the United States, and GLOBSEC for a conversation with four supreme allied commanders Europe (SACEURs): Generals Wes Clark (1997–2000), Phil Breedlove (2013–2016), Curtis Scaparrotti (2016–2019), and Tod Wolters (2019–2022).

Peter Rough, senior fellow and director of the Center on Europe and Eurasia, will moderate the discussion.

To attend, RSVP to David Altman at daltman@hudson.org.

Key Excerpts

See the following section for a full transcript.

1. NATO needs to learn the right lessons to implement emerging technologies.

General Wesley Clark:

Every war is unique, so you have to be careful about not relearning the lessons of the past war. But if you look at what’s going on in Ukraine today, a couple of things are obvious. . . . During the earlier conflicts—in the Gulf War—I didn’t see much innovation in the 1990s. We did bring the M1A1 tank in, and we used airpower in a unique way for the first 40 days in the Gulf War. When we went into Kosovo, it was with the same air power approach. We wanted to take the lights out in downtown Belgrade. That’s what our airman, Mike Short, wanted to do. We didn’t quite get to that because of the political constraints that were on us, but we used airpower effectively and we kept the ground forces in planning stage on that. But as you look at where we are today, software modifications are rolling out very, very quickly, and we’ve got to be able to match the pace of innovation that the Ukrainians have shown if we want to stay ahead on the battlefield.

General Curtis Scaparrotti:

There’s a lot being learned in the battlefield today about [emerging technologies]. You have AI in play as well, autonomous systems in a large way. For instance, Ukraine has done some very serious degradation of the Black Sea Fleet of the Russians, primarily through autonomous systems and long-range fires. Pretty remarkable, actually, for a small force. I would emphasize, as Wes said, that the innovation there is happening very quickly. There’s action and counteraction, I’m told in a general way, it’s about a six-week cycle, but for some technologies it’s day-to-day. And so those kinds of things are a part, I think, of the future of warfare from now on and something that we have to have a very decentralized and agile system at headquarters in C-II to be able to play in that type of a battlefield.

General Tod Wolters:

Now that the invasion has taken place, the two most remarkable points I’ll make have to do with integration and innovation. A twenty-first-century conflict is air-land, sea-space, and cyber, to include the information domain to include the nuclear arena. And a battlefield commander, regardless of which component they’re in charge of, has to have high situational awareness on what is taking place in each one of those domains all of the time to include whole of government’s approach to assisting in the campaign.

2. NATO does not have the infrastructure to respond to Russia’s hybrid warfare.

General Phil Breedlove:

Talking with a very close Georgian colleague, the hybrid fight going on in Georgia is palpable and measurable, and he believes that they are losing that fight in his country. I was with the interior minister of Moldova the other day. She is brilliant. She can walk you through basically very minor kinetic things that are passing in a hybrid manner inside her country and how the garrisons east of the Dniester River, Transnistria, are taking actions, moving people through and doing physical things as a part of their hybrid act and how little Moldova can counter these things.

And so frankly, I believe that we are so focused on the kinetic fight in Ukraine, which we have to be, but we are so focused on that, we are either unaware at a level of decision that we’re also going to have to start taking on this hybrid business. And the sum of all that’s happening in the hybrid spaces is immense. Just look at this reorganization of water space in the northern seas and all these things that Russia is doing because we’re focused so much on Ukraine, I believe they can think they can get away with this, even in NATO waters.

3. NATO’s cyber policy has evolved, but still needs significant improvement.

General Curtis Scaparrotti:

These are relatively new domains for NATO, but you can see the play and the importance of them in Ukraine. In fact, Russia started with cyberattacks before they ever did the physical attack. Fortunately, because there had been some work done, Ukraine was relatively well prepared and reacted pretty well to that, but it continues to be a part of the fight today and a very important one. And as far as NATO goes, they’ve begun now, obviously, to restructure and to add those capabilities, but I believe that they and the United States still have a good deal of work to do.

General Tod Wolters:

One of the interesting discoveries that I know General Scaparrotti and I were able to see firsthand during our tenure was the evolution of policy as it applies to confrontation in cyber and space. So as a US, at what point is a threshold crossed to where this is an activity in that domain that constitutes conflict/war? I think that’s where your question is going. We’ve made some significant gains in the United States from a space and cyber and nuclear perspective, from a policy perspective, applying a whole of government approach all the way down to the youngest soldier being able to implement so that everyone in that chain is aware of the practice that has to be executed in order to embrace an activity that we would say constitutes a conflict. We’ve improved in the US that that policy is better than it was in the past, but it still has a long ways to go.

Event Transcript

This transcription is automatically generated and edited lightly for accuracy. Please excuse any errors.

Peter Rough:

Good morning, and welcome to Hudson Institute. My name is Peter Rough. I’m a Senior Fellow here at Hudson and Director of the Center on Europe and Eurasia, and it’s my pleasure to quarterback today’s event on Supreme Allied Commanders on the past, present, and future of warfare.

Before I begin, I just want to say a special thanks to some of our partner organizations that are here. As some of you may know, Hudson has the privilege of co-hosting the public forum, which is the civil society event that will take place during the Washington Summit next month when President Biden welcomes 31 allied NATO countries to Washington, along with many other partner states. And some of our friends from those organizations are here at the Atlantic Council, came in force.

Hudson has the privilege of co-hosting the Public Forum, which is the civil society event that will take during the Washington Summit next month when President Biden welcomes 31 Allied NATO countries to Washington, along with many other partner states. And some of our friends from . . .

Along with the German Marshall Fund, which is also here. Thanks so much for being here. The Bratislava-based GLOBSEC, I think might be watching via our stream at home in Bratislava, although I think they’re based in Prague now. And a special thanks to the Center for New American Security, which along with Hudson is putting on some programming in the lead-up to the Washington Summit as part of the Institutional Partners work stream. So thanks to all of you for being here. Thanks to those of you who are in person and watching online. And of course, most of all, thanks to the SACEURs for taking the time being here today. They all have a distinguished career, quite obviously, for eventually being appointed Supreme Allied Commanders Europe, head of EUCOM. In chronological order, we’re joined today by General Wes Clark, General Philip Breedlove, Curtis Scaparrotti and Tod Wolters here in person. General Jones was supposed to be here. He had to beg off because he has some last-minute travel to the Middle East that came up.

And Admiral Stavridis and General Rolston send their regards. They too unfortunately couldn’t make it. But it’s great to have you all here to talk about the past, present, and future of warfare. So perhaps as an opening round, I would just go in the order that I just introduced you and start with you, General Clark. Could you maybe give us a feel for, since there is a major land war raging now in Ukraine, what you think is changing in warfare, what lessons should we take away from the major war that’s taking place right now in Ukraine?

General Wesley Clark:

Well, I think every war is unique, so you have to be careful about not relearning the lessons of the past war. But if you look at what’s going on in Ukraine today, a couple of things are obvious. Number one, we have to really understand electronic warfare. We’ve talked about it for a long time. We always knew the Russians, Soviets put a lot of effort in it, but we’ve built a lot of our force structure around Precision strike, really starting at the end of the Vietnam war with the TOW missile and the first laser guided bombs. And we got into precision strike as a way of not having to invest in heavy force structures. And so if you look at what’s happening in Ukraine, it looks like you might need a lot of ground troops and a lot of power, a lot of artillery, ammunition, et cetera.

Second thing is the pace of innovation. So during the earlier conflicts in the Gulf war, I didn’t see much innovation in the 1990s. We did bring the M1A1 tank in, and we used air power in a unique way for the first 40 days in the Gulf War. When we went into Kosovo, it was with the same air power approach. We wanted to take the lights out in downtown Belgrade. That’s what our airman, Mike Short, wanted to do. We didn’t quite get to that because of the political constraints that were on us, but we used air power effectively and we kept the ground forces in planning stage on that. But as you look at where we are today, software modifications are rolling out very, very quickly, and we’ve got to be able to match the pace of innovation that the Ukrainians have shown if we want to stay ahead on the battlefield. I think I should stop there. Thank you.

Peter Rough:

Thanks. And before we go to General Breedlove, I just want to welcome our friends from Lithuania. We have the Lithuanian ambassador who’s joined us. And Kęstutis Budrys, the head of the National Security Council in Lithuania. Chief advisor of the president of Lithuania who’s here as well. General Breedlove, over to you, sir.

General Phil Breedlove:

So first of all, thanks for having us together, and it’s an honor to be with these guys who I’ve learned so much from over the years. So I want to pick up a little bit on something that General Clark mentioned, and that is to remember that we don’t want to learn some lessons from past wars as well. I think I’m thought of in the community very much as a joint officer, but I want to make some remarks on air power in this war. The fact that the Ukrainian Air Force was so small, and let’s just give them immense credit for how well they did with limited assets, older assets, et cetera. And given some good intelligence, they have husbanded and use their force very well, but it was unable to do many of the missions that Western forces have grown to expect from air power.

On the Russian side, we had this magnificent, big air force that had some extremely new kit, but it’s very clear that the kit was not matched by trained pilots or mission-ready formations. And so Russia was absolutely unable to do suppression of enemy air defenses against a relatively small and less capable target. And Russia was unable to bring air power to the sport of ground forces until very late in this conflict. And so what we saw, a Russian Air Force that everyone feared was basically unable to do some of its most basic missions. And we all know, and I say this even though Tod is an F-15 guy, our job is to support the ground forces. We are to get through a phase in the air war so that we can then be a counter force capability to support ground forces. Russia still hasn’t really done that. Russia is a counter value air force and almost all their strikes are counter value against civilians, civilian infrastructure, fixed targets.

Russia has yet to truly bring its air forces to the support of the ground effort, which is something we fight so dearly to get to in Western air forces to bring air power to support of the ground mission. And so I think that as we learn lessons, and there are lots of great lessons that have come out of Russia’s failure, all of the things about RPAs. And Wes hit it on the head. EW has become a massive part of this war, and I would offer to you in my other SACEURs can correct my paper if they disagree, our military in America is not ready for this level of EW fight. We’ve got a long way to go. And there are methods that all the other surfaces bring to the EW fight, but we’ve got to figure this out.

So I too want to stop and let my other friends talk, but I just think that we need to be careful that we don’t try to take lessons from a war where the failure of air power has resulted in a World War I static attritional fight. Maneuver warfare supported by real air power would never leave us there. Over.

Peter Rough:

General Scaparrotti.

General Wesley Clark:

You’re on mute, Mike.

General Curtis Scaparrotti:

Yeah, I was getting echo. Thank you. First of all it’s my honor to be here with my colleagues, and I appreciate the invitation and the work that Hudson Institute and the others that support it, like GMF, the Atlantic Council that are involved, CNAS, et cetera. So thank you very much. I agree with all that’s been said. Coming in as the third player, I would go to the broader perspective of this, and that’s the play of space and cyberspace in this conflict. Between I and Tod, cyberspace was a new domain. As a SACEUR, you were officially . . . NATO was brought in. I think Tod, when you were there, they reinforced space and began to work with a domain center headquarters there, et cetera.

So these are relatively new domains for NATO play, but you can see the play and the importance of them in Ukraine. In fact, Russia started with cyber attacks before they ever did the physical attack. Unfortunately, because there had been some work done, Ukraine was relatively well prepared and reacted pretty well to that, but it continues to be a part of the fight today and a very important one. And as far as NATO goes, they’ve begun now, obviously, to restructure and to add those capabilities, but I believe that they and the United States still have a good deal of work to do, not only in these domains in particular, but as we look at that and the emerging technologies that both Wes and Phil have talked about, the interplay of those in a Nexus way, and that’s why the lessons learned today, I think, are ones that we need to be, not necessarily think that it’s done, but understand that as innovation happens and as we understand each of these new technologies and domains, how do they come to play together to add effect? And I think we’re very early in the process in that regard.

The next is just as Wes and Phil said, the emerging technologies, EW, absolutely, and I agree that the United States as well has a long way to go here. And there’s a lot being learned in the battlefield today about that. You have AI in play as well, autonomous systems in a large way. For instance, Ukraine has done some very serious degradation of the Black Sea fleet of the Russians, primarily through autonomous systems and long range fires. Pretty remarkable actually for a small force. And then as I would emphasize, as Wes said, that the innovation there is happening very quickly. There’s action and counteraction, I’m told on a general way, it’s about a six-week cycle, but for some technologies it’s day-to-day. And so those kinds of things are a part, I think, of future of warfare from now on and something that we have to have a very decentralized and agile system at headquarters in C-II to be able to play in that type of a battlefield. So another area that we and NATO I think, need to focus on. And I’ll stop there and let you go to Tom.

General Tod Wolters:

Well, first of all, Peter, thanks to you and Hudson and all the sponsors for getting us together. And I couldn’t agree more with what Wes and Phil and Scap had to say, and I will pick pieces and parts that apply to the 2019, 2022 setting. And the first thing that Wes Clark talked about was the uniqueness of each confrontation and conflict. And I think he’s so right, because the effectiveness of a nation or alliance’s ability to execute has to do with a whole of government, all domain approach and the personalities that are in play at the time. The good news is all of us are students of the game. So when the invasion kicked off in February of 2022, and I was serving a SACEUR, I had obviously studied what took place during General Clark’s timeframe with respect to the Air War with Serbia and his confrontations.

We actually got the chat one time, and obviously all the things that Phil Breedlove talked about were very much a player because the conflict between Russia and Ukraine actually kicked off in 2014. And that’s when General Breedlove was in the seat. And there were many things that he had to embrace during his timeframe that were very helpful to us as a shape in a SACEUR and a NATO alliance to be effective during that timeframe. And obviously I served as the air component Commander for General Scaparrotti during his time, and he was able to start the role of plans and effects in the battle space. And all of that came together at a time when it needed to. And luckily for the alliance, good decisions were made, quick decisions were made, and the forces were able to materialize in a position to deter, unfortunately, the invasion took place.

Now that the invasion has taken place, the two most remarkable points I’ll make have to do with integration and innovation. A twenty-first-century conflict is air-land, sea- space and cyber, to include the information domain to include the nuclear arena. And a battlefield commander, regardless of which component they’re in charge of, has to have high situational awareness on what is taking place in each one of those domains all of the time to include whole of government’s approach to assisting in the campaign. So in NATO today, that’s 31 nations, obviously to include the United States and hopefully soon to be 32, and hopefully one day to be 33 as recent discussions have taken place with Ukraine. But the whole of government, whole of military, all domain integrated approach into being effective in the battle space to make sure that you can accurately assess what is taking place and then be able to innovate in a very, very short timeframe knowing that the enemy of you could possess an ability to innovate as well. And that’s exactly what we’ve seen in Ukraine.

The good news is I like the odds with NATO, our 31 going on 32 nations are renowned for their ability to work together and innovate. Just as General Scaparrotti said, we’re not where we need to be in NATO, but we know where we need to go. And this all-domain approach with respect to whole of government, whole of military in all domains, to include a very, very keen emphasis on being willing to innovate in the middle of a conflict or something that makes this one unique.

Peter Rough:

Well, let me press you on that General Wolters, because when I watched the Russian military, I have to say that during the Karabakh War between Armenia and Azerbaijan, it was obvious to everyone that drones played a role in Azerbaijani’s victory over Armenia. And I had presumed that the Russians would’ve taken that lesson on board heading into the full scale invasion in 2022. Of course, the Bayraktars grew rather famous in their operational effectiveness, hitting Russian tanks and armor and an infantry in Ukraine. Today, one doesn’t hear about the Bayraktars all that much anymore, because of that innovation cycle and the learning and adaptability on the ground.

But that lesson there suggests to me that it’s really hard to watch a conflict from the outside and actually adapt and learn. The Russians certainly didn’t do it between Karabakh in the full scale invasion, but in the war, they’re able to rather quickly innovate or try to learn some of the lessons. How confident are you that the US, which is not a party to this conflict, can actually learn the lessons, and as a learning organization, the DOD can take on board some of these important lessons and actually drive it through our military reforms?

General Tod Wolters:

Peter, that’s a great question. I’m very confident in the US and all of our allies and partners in Europe’s ability to do exactly that. And to not do that is to lose. The cycle of lethality that is distributed by foes against America and foes against NAO is so powerful and so palpable and so well rehearsed in this area, anyone that’s engaged in this conflict that thinks that they don’t have to go to those lengths to be able to prepare is just not thinking adequately. And just as Phil Breedlove pointed out with respect to Russia’s first jaunt in February of 2022 into Ukraine, the basics of air-land integration were not executed on behalf of Russia. They were myopically focused on some of the toys and tricks that took place in those previous conflicts, and we’re fairly convinced that their degree of readiness in air-land integration in the initial push towards Kharkiv was significantly better than the forces that were present in Ukraine.

They were absolutely positively wrong. And this goes back to the comprehensive aspect of conflict. If you think you’ve got something taken care of in an EW spectrum, that’s great, but you still have to cover down on all of the basics and all of the domains. And Air-land integration has proven time and time again, if you’re not ready for it, it’s not simple, you’re probably not going to be effective. So this was just a classic case where Russia made a mistake with respect to their ability to apply ready forces at the right time at the right place, and they got caught in a conundrum. And it’s had an impact all the way to this very moment. And as we’ve all seen in the last 24 hours, Secretary Austin was not shy at all about making his comments with respect to Russia has made some initial pushes over the course of the last several weeks in the ground domain, but they’re starting to hit another stall factor.

And I would bet to say if we go back and take a look at some of the basics of air-land integration in their current adaptation stores going into Kharkiv, there’s probably some flaws there.

Peter Rough:

General Clark, you’re welcome to comment on that question as well, but if I can add to it, how do you assess the Russian military today? We saw General Cavoli, your successor as SACEUR in front of the House Armed Services Committee, I think in April, talking about the rapid reconstitution of the Russian Armed Forces more rapid than I think many of us anticipated. Give us a feel for how you read the Russian military as it sits in June of 2024.

General Wesley Clark:

Well, first, let me say that I’m really honored to be with this group, and I’m listening to all of my successors in command, and they’re so impressive and they’re so effective in hitting the points. Just a real pleasure to be here, and thank you again for including me.

Look, we’ve got to be really careful about not underestimating the Russian military. It’s easy to do, and we have to understand that in this war, in this information aspect of this war, Ukraine has always understood that if it portrayed itself as losing, it wasn’t going to stimulate more Western support, it was going to degrade the willingness of the allies to cast their lot with Ukraine. So the media from the beginning was really making fun of the Russian military. I did the first US Russian military staff talks when I was J-5 in ‘94, in the period, 94, 95, 96 through 98. I got to know a lot of the Russian Generals. They’re smart, they’re educated. It’s just an entirely different system. We give commands and our subordinates analyze the command and come back and tell us the tricks of implementation. And if we’re overly optimistic or wrong, somebody down there is going to speak up and say, “sir, you can’t do that. Let’s change the boundary. I can’t go across this river at this point, I need a little bit or with air power, or Sir, I need another artillery unit here because I just don’t have enough fires.”

In the Soviet lexicon and carried into the Russian forces, such questioning of a superior is tantamount to treason. You’re trying to disrupt the plan that you’ve been ordered to execute. Your job is to execute that plan. And so when we look at them at the blundering around on the battlefield, it’s easy to misunderstand what’s really happening out there. The Russian character, the Russian force is structured around grinding forward, grinding forward regardless of losses, grinding forward through bad command decisions above them. Taking losses. And somehow in Russia, thus far at least, it’s worked. Worked in World War II, working now, at least to some extent. So let’s don’t underestimate them. Technically they’re pretty smart. They’ve got China behind them, got Iran and sanctions busting behind them.

And if I could just say one more thing, they’ve got someone in charge who is an intelligence operative, unlike Stalin who had real military experience, but Mr. Putin is playing a very sophisticated game with us. He’s using nuclear threats, he’s using reflexive control against political leaders in the West. He knows what they’re afraid of, he dangles it out and uses it against them. And so we have to be very careful that to understand that this war is not simply a clash of armies and combined forces on a battlefield, it’s a much broader conflict. It involves nuclear, and right now, apparently the Russians are even using some chemical weapons against the Ukrainians. So we got to keep our eyes open on the big picture on this, top to bottom. Thank you.

Peter Rough:

And to that point, I’ve seen reports of the Russians suffering on average in recent days over 1,000 casualties, which is just an extraordinary number? General Breedlove, can I go to you next?

General Curtis Scaparrotti:

Mic?

General Wesley Clark:

Go ahead, Phil, you’re on mute.

General Curtis Scaparrotti:

You’re on mute.

General Phil Breedlove:

A quick two-figure, sorry, to your question, to General Wolters, I share his optimism that NATO and the US are adapting. Where I don’t feel optimistic is the speed of our adaptation. We recognize we need to do drones, and now we’ve got these big acquisition programs working on drones and things. And everything in American acquisition circles moves glacially compared to what we see, certainly the Ukrainians doing, and to some degree what the Russians are doing. So I think that we have great thinkers who are doing great work, but our system of bringing that work to the battlefield is not to the speed that we need. Sorry, go ahead with your question.

Peter Rough:

I was just going to ask you if you could also comment on your read on the Russian military where it stands as of today.

General Phil Breedlove:

Well, once again, I don’t want to sound sucking up here, but I think Wes nailed it. I mean, there is a lot of potential left in the Russians, and that potential is maybe not of the type that we would seek in our militaries, but their ability to slog this out and grind is still there. And I think that’s what Mr. Putin is counting on. He needs to keep this thing moving to the right. I think he fully expects that the West and maybe even the United States will change their approach and have new thinking, and all he has to do is survive to get there and keep the pressure on.

And I also am absolutely dismayed by the numbers they are losing, and I’m hearing the same numbers that were just mentioned upwards of 1,000 a day now. And that to us is horrendous. But to Mr. Putin, it is not horrendous. And he is, I think, still ready to keep moving right even if it gets worse, because he is unconcerned as we would be by that. And I think, just two more seconds, if we could get an information campaign that truly began to get to the Russian people what is happening out there, I think that would be an incredibly effective tool. Thank you.

Peter Rough:

General Scaparrotti.

General Curtis Scaparrotti:

Yeah, no, I agree with all that’s been said. I would just add to that, I think it’s quite remarkable if you look at the position that Russia is in, and yet Putin is planning for the future against NATO. He’s restructured his regional commands from joint ones and included and changed so that he could confront the addition of Sweden and Finland. They’ve been able to ramp up the production of their armored vehicles now almost six-fold in the midst of this, because they’re on a wartime economy. He’s put out a new modernization plan. So he clearly has a plan to not only finish this fight, but to continue with a force that’s there and can confront NATO beyond that. So they’re here to stay and we need to take them seriously.

Back to the point about NATO’s ability to take in these lessons learned. I agree here with all that was said there as well, and particularly our time aspect, I’d make two points. First is, there is a difference in NATO today based on even when I was there. You see not only the intent or the understanding of where we need to go, but you now see an increase in resources to the extent that they can begin to fulfill that. That’s a bit different than the time I was there. This past year, 11 percent increase for instance, and hopefully by the time of the summit, 18 nations at 2 percent or greater, with plans at least in the eastern countries and the Nordics to keep that going until the end of the decade perhaps. So I think that’s helpful to get after what Phil mentioned, and that is we’re not responding quickly enough and we’ve got an industrial base, not only in the United States, but particularly in Europe that needs to take a step up. And then my second point would be that one advantage that we have with respect to lessons learned is in the United States in particular, we’ve got subordinates all the way down to the deck plate that study this, that’s a part of their professional education, that have that kind of experience. And with the ability to decentralize and mission focus, as we call it, that type of chain of command, we can basically inculcate these, begin to train them and begin to bring them into our force as time goes on in a way that I think the Russians have a difficult time of doing.

Peter Rough:

Well, I see. We have a colleague here from Finland. And of course, Finland has a NATO adjacent center of excellence on hybrid warfare. I was just in Prague for a conference on the sidelines of the informal foreign ministerial that took place in the lead up to the Washington Summit. And in conversations with some of the senior European officials there, hybrid warfare came up regularly amongst the foreign ministers. It was one area where I think several of the ministers went off script and talked about some of the challenges that the alliance has experienced of late. If Vladimir Putin is fighting an outright conventional war in Ukraine and has not fought a similar word against the rest of NATO, he is prosecuting something of a hybrid campaign, it seems against NATO.

And my colleague Dan Kochis, who’s here today from the Center on Europe at Hudson, has a new op-ed out on this just last week, whether it be the buoys that were removed on the maritime border between Estonia and Russia, the Baltic interconnector sabotage, wind farms in the North Sea that are under attack, the Czech government’s accusing the Russians of meddling in their train infrastructure, and the list goes on and on, arson attacks that the English government, I think is accusing. The UK is accusing Russia of being involved in. So as the foreign ministers, I think in Prague contemplated or began to think about, at what point does a hybrid attack constitute an actual attack? How do we deal with that as a military alliance. And as a commander, how do you think about that? And maybe just to mix up the order, General Breedlove, we’ll start with you first this time.

General Phil Breedlove:

Well, it’s really interesting. I was in an incredibly good conversation just yesterday about the extent of Russian hybrid operations, and it appears that the west is really not paying attention to the fact that we need to address some of these things. And talking with a very close Georgian colleague, the hybrid fight going on in Georgia is palpable and measurable, and he believes that they are losing that fight in his country. I was with the Interior Minister of Moldova the other day. She is brilliant. She can walk you through basically very minor kinetic things that are passing in a hybrid manner inside her country and how the garrisons east of the Dniester River, Transnistria are taking actions, moving people through and doing physical things as a part of their hybrid act and how little Moldova can counter these things.

And so frankly, I believe that we are so focused on the kinetic fight in Ukraine, which is we have to be, but we are so focused on that, we are either unaware at a level of decision that we’re also going to have to start taking on this hybrid business. And the sum of all that’s happening in the hybrid spaces is immense. Just look at this reorganization of water space in the northern seas and all these things that Russia is doing because we’re focused so much on Ukraine, I believe they can think they can get away with this, even in NATO waters, even in NATO waters.

Peter Rough:

General Wolters.

General Tod Wolters:

Peter, back to the policy aspect of your question. One of the interesting discoveries that I know General Scaparrotti and I were able to see firsthand during our tenure was the evolution of policy as it applies to confrontation in cyber and space. So as a US, at what point is a threshold crossed to where this is an activity in that domain that constitutes conflict/war? I think that’s where your question is going. We’ve made some significant gains in the United States from a space and cyber and nuclear perspective, from a policy perspective, applying a whole of government approach all the way down to the youngest soldier being able to implement so that everyone in that chain is aware of the practice that has to be executed in order to embrace an activity that we would say constitutes a conflict. We’ve improved in the US that that policy is better than it was in the past, but it still has a long ways to go.

We’ve significantly improved in the great nations of Europe and NATO in that same area, and achieved assistance from large government bodies, EU with NATO, to achieve gains in those areas. Because we are western democratic nations that have a value system, these policies actually matter to us when it comes to armed conflict. I don’t think the same can be said for the way Russia conducts their activity from a hybrid perspective. So the trend for the US and NATO and hybrid warfare is improving, and that whole of government policy that applies in cyber and in space is making gains, but we still have a long ways to go. We must embrace this. It is ongoing. Just as Phil Breedlove said, it will be going for a very, very long period of time. It’ll come in different shapes, forms, and fashions.

And if you don’t have the basic policy down that constitutes when you’ve crossed the line of conflict slash war as a nation with our Western democratic values, we could be in a world of hurt. Luckily, we’re not there. We’ve made some good gains as a US, and as I said, so have many of the nations of NATO. But this hybrid warfare, which I really bucket in the category of all domain activity, is something that we’re going to have to embrace today and in the future. And we’re getting after it. We’re probably not going as fast as any of the commanders behind me would prefer or as I would prefer

Peter Rough:

General Scaparrotti.

General Curtis Scaparrotti:

Yeah, thank you. It’s interesting to me as you look at . . . Let’s go to the disinformation part of this. And I agree with Phil. I was in four countries here just recently in the last month in Europe and the Nordics, went across the Nordics in December. Europe is very well aware of the disinformation campaign and campaign of destabilization they’re doing through that. I was in Moldova here about three weeks ago. They laid out for me, Phil as well, and in great detail, the impacts there. And they believe that Russia is spending $55 million a loan on Moldova. So they believe that this is worth that kind of investment. To the point on this is that NATO actually, at least at the time I left in command, I thought NATO was more agile and understanding disinformation and having apparatus that could very quickly begin to foresee it coming and respond where they needed to, developed basically, Phil, during your time, and then added to that throughout.

They had a pretty good picture I think in the system there at NATO, better than United States, frankly. In the United States. I think one of our problems is we have this cultural . . . We just culturally don’t like dealing within the information domain. We’re very restrictive in our ability to do that, and I think it does hurt us a great deal in terms of our agility there. During Phil’s time, he started the Russia information group, the RIG. I think that’s an important development, and it has continued to develop over time, precisely to deal with, both to understand and then deal with Russian disinformation from a interagency whole of government view, which Tod mentioned. So it’s in place, we are getting better, but we’re not dealing with at all with respect to both the agility and the investment that we need to make.

Peter Rough:

General Clark.

General Wesley Clark:

Well, I agree with everything that Tod and Phil and Mike have said. Let me take it to the next level. So hybrid warfare goes into the political makeup of democracies. Yesterday, I got a note from a leader in North Macedonia who said that his party, the majority Albanian party, had been forced out of the government because the government, which is dominated by the Slavic party, wants to align itself against Bulgaria, against the EU, against NATO, and with Viktor Orbán. Now, this isn’t a bunch of ordinary citizens who are farmers and people Macedonia saying, “Gee, I think EU is a bad idea.” It is an evidence of the Russian fingers that go throughout Europe at the political level. And so hybrid warfare starts maybe for us in the military with cyber, we’re worried about space, but it ultimately ends up in the lap of the politicians. And what Mike says about disinformation is exactly right.

It’s out there, but it’s even worse than that. It’s reflexive control. So if you know what your political leader’s afraid of or what you want him to do, you just trot out the little indicator. He says, “Oh my God, we can’t do this.” And look at how we criticized the Ukrainian strike on this strategic radar. And from the lesson I would’ve hoped Putin would take from this is, “Hey, these Ukrainians, they’re pretty tough. I need to find a way out of this before they take me down.” But the response from some in the west was, “Oh gosh, you might escalate the conflict. Don’t strike that and do that.” This is reflexive control in action. And so if you look at where we are, and I’m going to say . . . I’m going to cross this line. I’m an old guy. I’ve been around this for a long time, and I did throw my hat in the ring once because I saw us making a strategic blunder in Iraq.

Look, the American political system is a domain of conflict right now, and that’s simply a fact. And so about whether or not the United States will continue to support Ukraine, about whether the American system of justice is effective, about whether democracy works, all of this, this is old play for the Soviets and their successors in Russia. When I worked for General Hagen in 1978–79, as his assistant executive officer, we would watch these kinds of stories emerge out of obscure Indian publications, which were then intended to be picked up in the UK, and then picked up in the United States. Didn’t work. We used to laugh at them. They were so amateurish and ham handed. “America’s going to have a civil war,” said some Indian publication in 1978, making up something. Today with social media, it’s on our doorstep. It’s in our movies. So the attack space has enlarged for hybrid warfare, and it’s not really our military responsibility.

We have to educate through our own experiences and our personal relationships. We have to educate our leadership to do the right thing. Every two to four years, we bring new leaders in at the political level and we swear our allegiance to them, and they haven’t seen . . . They don’t have the history. They haven’t seen, in many cases, the intel, and so there’s an educational period. And in that educational period, that’s where Russia and hybrid warfare excelled.

Peter Rough:

Yeah, we may be uncomfortable with information campaigns against our adversaries, but they’re certainly comfortable launching them against us, and we tend to propagandize ourselves more than we might target countries. I’d like to go to the front row with a question, but before I do that, I was just speaking yesterday with a colleague from our Center for Defense Concepts and Technology who were describing a study there running for a country with demographic challenges, and one of the forced design requirements that they had in this project they’re running is to design systems that would require fewer persons to man them. And that raised in my mind a question I want to put to you all, which is related to that. We’re seeing real challenges in recruitment in the United States and across some of our NATO allied partners. Do you all have any, since you’re deeply entrenched in military communities, ideas or any explanations for why we’re struggling to hit our recruitment numbers right now? General Breedlove, if you have any thoughts on that, I’d love to go to you first.

General Phil Breedlove:

I’d like to reorient or just comment on the question a tiny bit. And I think we have . . . I understand where you’re going and we should answer that, but I want to say one thing. A lot of countries can match America now or nearly match America now in building and fielding it and capability, but I believe in my heart of hearts, that what has set American militaries apart forever is the American military fighting man and woman. And the way that we train, educate, and bring on leaders, train, educate, and bring on NCOs, and train and educate those young people who actually do the mission, I believe is what really sets America apart. And so I think we need to keep focus on the fact that it is our soldiers, sailors, airmen, marines, and now guardians and guardsmen. This is the difference, in my opinion, between us and them. And we need to keep focused on getting the right kind of people and numbers so that we can maintain that. Sorry for editing.

Peter Rough:

No, I would just add to that. One thing, I think that on the Russian reconstitution, is sometimes overlooked, we can look at sheer numbers, but it takes a long time to grow in able military. The NCOs are the backbone of our own military, and you don’t grow those overnight. And so Russia might be able to throw new persons into the battle, but they’ve lost a good chunk of what is I think their most effective fighting force. Any of the other three want to tackle the recruitment challenge question? General Scaparrotti.

General Curtis Scaparrotti:

One thing I would point out is in the west and in the United States in particular, we’ve got a very small percentage of those who serve today and have served over the past 20 years or so. And so the military is not as well integrated or understood across our society as it once was coming out of World War II, Korea, et cetera. All my uncles and all of them served, et cetera. My grandfather served. That’s not the case anymore in our society, and it’s not the case in Europe. So that’s a factor here. And then secondly, you can see that in the United States because in talking to the recruiters here, the propensity to serve is impacted by the parents. The recruiter focuses on the parent first because they have real influence on whether the youngster wants to sign up and become a part of our military. Often, in fact, they’ll find someone who is inclined to serve, is interested in it, but the parents are not. And so that, I think is probably true in Europe, as well as the United States here, and it’s having an impact on our ability to recruit.

General Wesley Clark:

I think we’re going to have to take another look at the volunteer force, the incentives, how it’s structured, how we organize it. It’s just time to do that. It’s 50 years really since we did it. And we did it . . . I was a captain and I was part of that effort to create the modern volunteer force. And we did it by offering incentives, and the purpose of it was to enable expeditionary forces without the kind of demonstrations that we saw during the Vietnam War caused by the draft. It’s been 50 years, volunteer force has served us really well. Nobody would’ve expected in 1971 that we would be able to fight through 20 years of Iraq and Afghanistan with that force, and have it do as well as it’s done. But as Mike just said, we’ve got to re-look at this, because many of the incentives that we used and the relationships that we relied on have changed. Others have taken our incentives and used them for their own purposes from the US government, things like scholarships and educational assistance. And at the same time, as Mike said, the parental and cultural support for public service has declined. So we need to reconsider this. America needs a strong armed forces, and it needs a citizenry willing to serve.

General Tod Wolters:

And Peter, part of the innovation process that makes us so special as a US Department of Defense and the militaries of the nations of Europe that are so good, innovation applies all the way to the service level. Just as Wes Clark was talking about, you, you’ve got to go inside of the Army, inside of the Navy, inside of the Air Force, and you’ve got to find ways to incentivize different paradigms than you have in the past with respect to bonuses, or years in service that allow you to reach certain thresholds. So all of that comes into play, but I go back to what Phil Breedlove said, we still have the best young women and men in the history of humanity. Our US Department of Defense has a force with unequal lethality, and it is because of the people that execute the mission.

Peter Rough:

We’ll go now to Kęstutis Budrys, the chief advisor to the president of Lithuania.

Kęstutis Budrys:

Thank you. Thank you for opportunity being here, thank you for inviting. And it’s absolutely unique for me to see four secures in front and listening to you all on the current events. And I wanted to comment on Russia’s escalation within NATO. One thing, another thing I wanted to ask you as I have this unique opportunity, on your previous positions, and on the reflections on being secure in NATO.

So on Russia’s current activities, I think that we have to stress the difference between the hybrid operations that we described and we were talking about, and within NATO, that was 10 and more years ago, and what we are seeing right now. Then it was yes, about adding new domains like cyber, or being it informational domain, seeing informational operations from Russia, cyber-enabled information operations, cyber-intelligence collection, disruption, all these, organization of international law. We saw all these elements and they were new because they were against us, and they were designed against us, and conducted against us, in centralized the role of the government way.

And that was something to recognize, to understand, to identify and go after. And that was before, I would say last year when Russia conduct started to conduct kinetic operations within NATO. Yes, Moldova, yes, Ukraine 10 years, that was a bit different area, and a bit different conduct. Now it’s within our territory. And then started from the Baltics with kinetic operations, with the attacking our public monuments, public servant servants’ cars, for example, in the Baltic and the other. And the very recent ones is with the kinetic attacks against people, against human, against their politicians, opposition. Now we have the critical infrastructure. Now we have the, in Lithuania’s case, we have the shopping mall that is absolutely not connected to the ongoing war or to their citizens, defectors or political opposition. So they’re escalating it up.

And this is not hybrid anymore, as we saw with some shadow, some smoke or something that we cannot recognize. This is the non-conventional operations against NATO that is conducted by military intelligence agents that are recruited in one way or another. So in our assessment that changes the overall picture. And they’re climbing the ladder against the NATO in this way. So this is different. This is new. This is not something that we saw 10 years ago, and we have to react differently.

So my question is, what would be your advice if you would see it happening in US, for example, and you have the clear attribution? It’s not about guessing, it’s not about hypothesis, who is behind it, but you have the clear attribution. What has to be the reaction? And where is the threshold for the conventional reaction? So it’s comment and question. And another one on the political element in overall our planning and processes, and I’m just following general Clark’s comment on the politicians who are making decisions on the end of the day.

Because when we are looking at the papers, how we design all the decision-making process from indicators to the timelines for reinforcement of our posture, talking about the Eastern flank, when we’ll make decision to do this or that, we know that politicians are making the decisions. And looking at the Ukraine as the one big, for us source to learn politicians and their decisions even before the February 22, is also something to learn. How the intelligence information was perceived. What were the political assessment of intelligence assessment? What decisions were made and not made? And I’m going, going, going.

So knowing all this and that even in NATO, not everything has to happen in the way that we design, in smooth military way. And knowing your authorities, previous authorities, do you think that expansion of secure authorities to make the decision on their own and to expand on this one would limit the risk, the political risk, that we will be too late or too small in what we decide how we have to react dealing with Russia? Thank you.

Peter Rough:

I’ll throw that to any . . . General Clark, I see you’re ready to go. And then General Breedlove next.

General Wesley Clark:

First of all, there was apparently an incident in the vicinity of Fort Liberty in North Carolina a few days ago, in which two Russian-speaking Chechens were doing reconnaissance on the home of a special forces colonel. He confronted them. They claimed to be electrical utility workers. They weren’t in uniform, they had no identification. Somehow it got out of hand and he shot one of them, and they got the license plate of the other guy as he escaped, the FBI’s investigating. We have to tighten up our internal security in the United States because we know that there are Russian Chinese and Iranian hit teams in this country right now. And that’s the case all through.

But I think we have to be careful with the idea of giving the trigger to the military on certain actions here, because we have to have the support of the public. The military works for the public, for our governments. And so I would say that the responsibility for strengthening internal security and recognizing the threat falls to our elected leaders. We have to provide the information so the voters can pick the right leaders.

Peter Rough:

General Breedlove, I think you wanted to-

General Phil Breedlove:

So I would pile on to that, I would like to carry on the next sentence what General Clark just said. I really believe that first of all, it was a really excellent, comprehensive question with sort of two roads to go down. But I believe that the answer is really much the same. And it starts with policy, where our elected officials take our policy.

Right now, I would observe, I would observe that in my government and many European governments, we are stepping all over ourselves to avoid conflict with Russia. We are not being . . . In any way confronting Russia on their actions. And this goes way beyond the kinetic field that I’m talking about, and it gets into the several things you were talking about, and General Clark just mentioned. There are actions happening in many NATO nations, and I believe as a matter of policy that some of our Western leaders do not want to take these things on.

When Russia shot down a US drone, I don’t like those words as you know, but when Russia shot down a US drone in the Black Sea, what did we do? We retreated. We gave Russia more international airspace and sea space. We backed away from them so that we would lessen the possibility of a conflict. And I think the questions you are asking, sir, are much in the same zone. We know about these things happening in our countries, but we do not have a policy now that says we’re going to take them on, because we are trying to avoid conflict. This is what General Clark talked about so much in reflexive control. We are on the backside of that decision process.

Peter Rough:

General Scaparrotti.

General Curtis Scaparrotti:

Yeah, I agree with all that. And I would just add that another component of this is a responsibility to educate the populace, both in Europe and the United States as to really what’s going on. I mean, that’s part of deterring this, and it’s part of having the support our politicians need to take the action that we’re talking about.

General Tod Wolters:

Yeah. Clear, concise national policy. It is an absolute must. It’s a civilian-led military expanding SACEUR’s authorities is wonderful as long as the policies are in place to support that. And as you well know, that took place in December of 2021 all the way until January, February of 2022. The expansion of SACEUR’s authorities to be able to take the enhanced battle groups in Eastern Europe and allow them to conduct readiness activities was granted by the NAC, a civilian organization with clear-cut policy that defined those authorities.

And just as all the three previous SACEURs talked about in future conflicts, these thresholds of what constitutes a conflict in space and in cyber and with EW are very, very fuzzy. And we have to have concrete policy from the whole of government all the way down to the enactor with respect to the military to be successful. And if we don’t, we start to flip our values out the window, and then we start to inherit a lot more problems. And by the way, a big thanks to you and your nation for the Vilnius activity last year. I can’t believe it’s already been one year and here we are at another summit, but it was a wonderful summit last year in Vilnius, so thank both of you.

Peter Rough:

Perhaps as a closing question-

General Wesley Clark:

Can I say one thing just to circle this thing back to Lithuania? Look, Khrushchev once told an American president, he said, “We know you better than you know yourselves.” And the record of democracies is that democracies are always slow to act. But one thing that when I was SACEUR, Slobodan Milosevic had to learn the hard way. He thought that he would win in Kosovo because he wanted it more than NATO did. But what he didn’t understand is that an alliance of democracies, once its sets its goal and its policies, it doesn’t back off. And Mr. Putin needs to understand this. NATO and our Democratic nations may be slow to anger. We may be slow to recognize that we’re in a confrontation, whether we want to say it or not. Once we recognize it, it’s over for Mr. Putin. He will lose that confrontation.

Peter Rough:

How can I ask another question after that rousing conclusion? So I’ll refrain from doing so. And thank you four gentlemen, it’s been a real honor to be able to host you all here today. On behalf of the Public Forum Consortium, the Atlantic Council, the German Marshall Fund of the United States, GLOBSEC, the Center for New American Security, and of course Hudson Institute, thank you so much for your service. Thank you for agreeing to do this pro bono, to try to generate a little bit of attention and conversation in lead up to the Washington Summit. It’s been a real pleasure, and you are always welcome at Hudson Institute. Thank you, gentlemen.

General Wesley Clark:

Thank you.

General Tod Wolters:

Thanks to Hudson.

UK Shadow Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Affairs the Rt. Hon. Priti Patel, MP, will join Hudson for a conversation on the future of the special relationship and what the adoption of a conservative foreign policy would mean for Britain and the transatlantic alliance.

Join Distinguished Fellow Mike Gallagher and Congressman Rob Wittman (R-VA) for a discussion on the congressman’s recently introduced Securing Essential and Critical US Resources and Elements (SECURE Minerals) Act and Congress’s role in securing America’s economic security.

Join Hudson for an expert panel on why these deals are so important for both nations, what they mean for the future of US supply chains, and what potential challenges remain for implementing these deals.