Mexico Navigates New Challenges

Event will also air live on this page.

Inquiries: [email protected].

Chairman, México Evalúa

Founder and CEO, AOM Trade and Investment Advisors

Former Deputy Chief of Mission, US Embassy in Mexico

Adjunct Fellow

Daniel Batlle is an adjunct fellow at Hudson Institute. His work focuses on Latin America and the Caribbean.

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum faces a formidable set of challenges with enormous stakes for the country. New American tariffs signal a turning point in supply chain integration with the United States and will disrupt Mexico’s most productive economic sectors. And although Sheinbaum has taken a stronger approach to organized crime by extraditing cartel leaders, increasing arrests, and seizing more fentanyl, the recent discovery of a mass grave of cartel victims underscores the country’s rule-of-law crisis.

Join Hudson Institute for a panel discussion examining the potential scenarios for Mexico and the future of the US-Mexico relationship.

Event Transcript

This transcription is automatically generated and edited lightly for accuracy. Please excuse any errors.

Daniel Batlle:

Good morning and welcome to Hudson Institute. My name is Daniel Batlle and I have been looking forward to this discussion. Events of the past several weeks have shown that many of the assumptions about the outlook for Mexico and for US-Mexico relations need to be set aside. Mexico confronts a series of deep challenges and I think this is a timely discussion on the nature of these challenges and whether the Mexican government is approaching them in a productive way. We have a fantastic panel today. Luis Rubio is chairman of the Mexico think tank, México Evalúa. He has been president of the Mexican Foreign Affairs Council, COMEXI, and has written over 52 books.

Antonio Ortiz-Mena is founder and CEO of AOM Advisors and is an adjunct faculty member at Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service. He is also chairman of the USMCA Committee at the Mexican Foreign Trade Council. And John Creamer, retired from the US government after a 37-year career in the foreign service. Much of it working on law enforcement and security cooperation. He served as Deputy Chief of Mission at the US Embassy in Mexico from 2018 to 2021. Luis, I want to start with you. I have found your writing on Mexican politics to be very clarifying and you’ve described how many of Mexico’s current challenges are a result of choices made by the previous government of President Lopez Obrador. Can you describe some of those challenges and assess whether the shifts we’re seeing with President Claudia Sheinbaum will entail different outcomes for Mexico going forward?

Luis Rubio:

Good morning. Thank you, Daniel. I’d like, I think to take a slightly longer view and then end up answering your question. Let me make three points. Mexico has had serious problems for a long time. During the 1980s, this came to a head and Mexico began trying to reform itself and reforming required, Mexico finally understood, getting to change its positions, its history vis-a-vis the US. For a hundred years almost Mexicans had seen the US as an enemy, and Mexico’s governments had exploited the 1847 war as an instrument of political control, of domestic political control. So the turnabout that Mexico had to do in the 1980s to get its reforms going was enormous. And the reason why Mexico approached the US at that time was in order to borrow American institutions because Mexican institutions were too weak, too frail to serve as sources of certainty for investors, for savers, for business people, and for the population at large.

So NAFTA ended up being as much a political institution as it was an economic or trading and investment one. Among the reforms that Mexico launched, there was economic reforms that were important, but also some political reforms that came about immediately after NAFTA. The first one was the reforming of the electoral institutions in order to level the playing field, and that’s how Mexico ended up having free and fair elections that were recognized widely. And the PRI, the party that governed Mexico for 70 years was finally defeated in 2000 with Vicente Fox. What Mexico did not reform at that time was its governance institutions.

It did not change the structure of the government. It did not address the relations between the federal government and the state governors. It did not define and develop the relationship between the three branches of government. It did not build and develop security institutions because the government in the past had been so, so powerful, the federal government, that it could control everything. Once the PRI and the government divorced, to put it one way, the security institutions simply collapsed and there aren’t any new security institutions as a result of that. So the security issues come as a result of that.

But a fundamental point here is that the US and Mexico saw NAFTA in very different ways and much of the seeds of what has happened since are the result of that difference. Mexico saw NAFTA as the end of the process, as a way to guarantee reforms that had already been made. Whereas the US saw NAFTA as the opportunity it was giving Mexico to transform itself. So much of the problems that we see today are the result of that. Second point is that today, fast-forward 35 years, Mexican governments have had it too easy. And the biggest beneficiary of that was Lopez Obrador. Because of migration to the US as the US demanded labor, there was much less pressure to change things in Mexico, to reform things in Mexico and NAFTA guaranteed access to the US market. And the combination of those two made it very easy for governments to simply avoid making big decisions or affecting significant interests, political, economic union and so on.

And that’s where Morena comes in. Morena won the elections of 2018 largely for three reasons. One is that the promise of democracy that Lopez Obrador became associated with was not perceived as having delivered. Second, the promises of a comeback by PRI with Peña Nieto was also not seen as successful. And the third is much simpler, and that was that people were improving their lot. The numbers show that there was significant improvement, but inequality grew nonetheless and people didn’t appreciate being left behind even though their lot had improved. So they didn’t keep up with the Joneses, in the American expression.

Lopez Obrador was a genius, like somebody governing these countries, at exploiting these differences. He was extremely adept at finding ways to build a constituency, a clientele. And he spent his whole six years avoiding economic growth, not because he didn’t like economic growth, but because he saw economic growth as a way for people to liberate themselves from the loyalties to the party. So he spent those six years developing a clientele which materialized successfully in the 2024 elections where he was the actual candidate. President Sheinbaum is extremely popular at about 84, 83 percent. But however, if you look at the numbers in the same polls, they show something slightly different. They show that 30 percent of Mexicans are diehard supporters of Morena, 10 percent are diehard opponents of Morena, and 60 percent see themselves as orphans and there is no opposition to catch that. So that’s another important conundrum.

So the third point, and quickly just to finish, the fundamental objective of Mexico’s reforms and of approaching the US back in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s was to find a source of certainty. And what we’re seeing today is exactly the opposite. The source of certainty has now become the source of uncertainty. Mexico’s president has tried to turn that around by saying that Mexico has got it less bad than others and that’s the source of certainty that we should have. But obviously that’s not going to hold for long. But the main point, going back to your question, Daniel, is that Mexico has had very little, if any, new greenfield investments in the last seven years since Lopez Obrador came into the government. And the reforms that he enacted only the last month of his administration have made it much more difficult for Mexico to be able to attract investment and to make it possible to develop in the future.

Daniel Batlle:

Thank you, Luis. You covered a lot of ground there and I will come back to you on some of the topics you raised, but I want to go to John and talk about security. The case of the Nueva Generación Cartel training camp and mass grave found in Jalisco really highlights the extent of the security crisis in Mexico. Can you talk about how the Teuchitlán case fits into the larger security situation in Mexico?

John Creamer:

Sure. Good morning everyone. Happy to be here. Unfortunately, Teuchitlán. . . Actually there are many Teuchitláns out there in Mexico and it’s a real human tragedy as well as highlighting the problems that face the country. And I think it shows the extent to which local security forces or local authorities either are complicit or ineffective in acting against these groups. It shows that in many ways they can act with impunity. And while there’s debates if drug trafficking organizations or organized crime control territory in Mexico, it clearly shows the kind of parallel structures where they’ve been created where they could operate, like I say, without really any concern for interference by local authorities.

And of course, what’s striking is that security forces that visited Teuchitlán several months before became big news and yet really nothing had been done. It’s really, in that sense, quite frightening. We’ll see if it itself becomes a kind of galvanizing event in terms of a mobilizing people around security issues. There’s just been many such incidents in the past and in general, they’ve not tended to have too much impact in electoral terms, but we’ll see what happens in this instance. I do think that in terms of President Sheinbaum and her policies, we’d already seen a recognition on her part. Although she always says what she’s doing is quite consistent with the Obrasso’s strategy of her predecessor, President Lopez Obrador, had actually already pivoted away from that approach.

And they’ve moved to a much more aggressive campaign targeting organized crime organizations. So particularly what they call the generators of violence. And she’s appointed as the Secretary for Security and Citizen Protection, Omar García Harfuch, who was her chief of police in Mexico City. He enjoys her confidence and support. He himself has a team of people who have worked with him, both back in the federal police and at the Fiscalía. And so they are making some major moves, shifts towards a strategy attacking criminal organizations, particularly generators of violence using intelligence driven operations, trying to promote much greater collaboration between prosecutors and investigators, something they did fairly successfully at the level of the city.

They’re trying to increase the number of investigators, both through extending investigative authorities to other organizations and increasing actually hiring of investigators. Also, they’re trying, because of his support with the president, to do a more effective job in coordinating the different federal security forces as well as with the state and municipal authorities. Certainly not an easy task, but I think some of the initial signs have been somewhat encouraging. But that said. . . And actually in that point, I also would say that it seems that the Mexican authorities are starting to cooperate again much more closely with the US in terms of information sharing.

We saw President Sheinbaum essentially step out and say, “Yes, the reports on US drones that were in Mexico were there at the request of the Mexican government,” highlighting, again, perhaps closer cooperation with the US. But that said, there are major challenges. It’s not as if there’s been a significant commitment of additional resources to the security institutions. There’s still a fragmentation with the National Guard under the Army, SEDENA, as opposed to under the Secretary for Public Security. There is a pending judicial reform, the election of all the judges, which even if it produces competent and quality judges, it puts a whole period of uncertainty and throws the whole judiciary into flux at a key moment when you’re trying to move forward the security.

It’s not as if the Mexican judicial system has been particularly effective in the past, but that puts a whole question mark on that. And again, I think you look at say the Fiscalías, both at the federal and the state level, and they’ve really largely been ineffective in working. And so it’s hard to go forward with a successful security strategy if you continue to have major problems, both in terms of your Fiscalía, ability to prosecute and hold people accountable, and a judicial system, which is pretty ineffective and unresponsive. So, the challenge is to remain. I do think her strategy is a move in the right direction. She’s clearly committed a lot of her political prestige to that, but we’ll see how this works out. There’s a long way to go.

Daniel Batlle:

Okay. Antonio, where does the announcement on tariffs from Wednesday leave Mexico? What is your outlook for the Mexican economy? When you look at the announcement Wednesday, and the tariffs that were announced in March?

Antonio Ortiz-Mena:

Okay, how long do we have? Let me take the same tack that Luis took. Let me take a step back to give you a context of what I believe happened, and then make reference to the specifics about Mexico-US economic relations, and USMGA and the prospects.

So, what happened on April 2nd, and I do think that everybody will remember that date, April 2nd, 2025 was the biggest change in global trade policy since at least 1930. In 1930, the US House and Senate passed the Smoot-Hawley Act, which raised tariffs with the aim of protecting farmers and industrial workers. What happened back then is that those tariffs resulted in other countries retaliating and US farm workers and industrial workers being worse off than before the tariffs. And in fact, four years later, the US Congress passed something called the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act, which started to backtrack on the imposition of those tariffs, and that in turn led to the system that the victorious allies created after World War II, which is the GATT and the WTO.

Now, that system is very important because it had the aim to avoid tit-for-tat policies, or beggar-thy-neighbor policies, that would make everybody worse off, and to try to establish a legal basis to resolve trade disputes. It wasn’t perfect, but we wanted to avoid a free-for-all. What happened on April 2nd, in my view, was that the US acted unilaterally. Many people believe that its actions are inconsistent with its commitments under the WTO, its commitments under regional trade agreements, including the USMCA, and that creates a whole lot of uncertainty.

Some countries might retaliate and everybody might be worse off. In this case, you can see Canada and Mexico behaving differently. Canada just announced a 25 percent tariffs on US autos. Mexico’s [inaudible 00:18:09] pat for the time being. But the key issue is that this unilateral action creates uncertainty and generates risk for countries responding in kind.

In terms of the regional impact, some people say that Canada and Mexico fared better than every other country. The base tariff was 10 percent, other countries got higher rates, Canada and Mexico got 0 percent largely, with some exceptions for autos and auto industries. But the key question here is the basis for that decision, and when that decision can be reversed, and what happens to goods that are not traded under the USMCA?

By some estimates, about 40 percent of Mexican exports to the US used to enter the US through the WTO rules, and the US tariffs under the WTO were pretty low. For Mexico, those tariffs are now 25 percent. I’m sorry to get a bit wonky, but it’s just important to understand what happened. Under the WTO, you have to establish the same tariff to every country. You can vary by product, but not by country. That’s why it’s called the most favorite nation, you treat all nations equally.

So, what the US is doing is treating nations differently. Canada and Mexico get a 25 percent tariff for allegedly not cooperating enough on fentanyl traffic and on undocumented migration. And according to the April 2nd announcement, at some point in the future, by the US’ own decision, that 25 percent tariff can come back to 12 percent.

Now, if you want to look at the glass half full, we could say that having zero tariff is better than having 10 or 25 or over 40, that is true. However, the main concern remains uncertainty. How long will the US stick with its current policy? How will it deal with automobiles? Will it respect the agreements it strikes? I want to point out that about two years ago, a USMCA panel on precisely automobile rules of origin made a decision against the US. This is under the Biden administration, and the Biden administration decided not to comply with that decision, and the current administration still has not complied with this decision.

So, if the US is not abiding by its international commitments, and Mexico and Canada as well as other countries just need to expect to be treated fairly, that does not create a sustainable basis for regional investment and for regional trade. Yes, it could certainly have been worse, but I would say the big challenge for the US, for Canada, and for Mexico, is to come up with a set of stable and clear rules to foster trade and investment in the region. I believe that if the US goes it alone, the economic effects in the US, I’m not speaking about Canada or Mexico, will be very negative in terms of growth, in terms of employment, in terms of production, and in terms of exports.

Let me give you two examples, one from the industrial sector, one from Ag. In terms of the industrial sector, the US is centering its attention on autos and auto parts. If it wants to produce all of its automobiles in the US, by definition the production will be much, much higher, because it wants to produce them in a labor-intensive way with very high wages. I’m not saying people shouldn’t be paid high wages, but maybe they should be paid high wages in services, or in other industries. But if you want to produce autos with high wages, it’ll be very difficult for the US to export those automobiles, because they will be more expensive than the competition, and that would not help reduce the trade deficit of the US.

Secondly, if other countries retaliate against the US, then the exports from the US might face additional tariffs that were not existing now. So, just using that example I think shows some of the problems. If, however, there’s a lot of investment in the auto industry across Mexico, the US and Canada, both employment can increase, production, can increase, exports would be more competitive, and it would be a win-win situation. That’s the way I see it, putting that example out. Let me turn to ag.

Mexico is the main trade partner for the US, Canada is the second, China comes third. A lot of the discussion around the economic effects of these measures have to do with what the US buys, what the US imports. Will there be inflation because of more expensive tomatoes or fruits or vegetables, what have you? But the other side of the coin, Daniel, is what the US exports in ag to Canada and to Mexico. Mexico is an absolutely critical market for US ag production in items such as corn and wheat and barley and pork, right? And we’re not talking about bringing investments back home. Those items are already produced in the US. A lot of them are in the Midwest. And if they’re not shipped to Mexico or Canada, it’ll be very difficult to channel those products in general, because agricultural markets are protected, but I can bet that a lot of the retaliation will affect US ag exports.

So, from a self-interested perspective from the US, I think it would make sense to, number one, abide by its commitments fully. And number two, going forward to establish clarity and stability. That’s the way I look at things, Daniel.

Daniel Batlle:

Yeah, so on that, on the clarity and stability that everyone wants, some have suggested that the Mexican government should seek to move the revision of USMCA forward, to try to get that clarity as early as possible. Do you think that’s a good idea? Would that be productive?

Antonio Ortiz-Mena:

Look, Daniel, I think some people are hoping for something like D-Day, a big day, something will happen, hopefully good, maybe bad. I think there will be no D-Day, I don’t think there will be no D-Day if the review is brought forward, or after it’s successfully reviewed, et cetera. I think that there will be a certain degree of uncertainty throughout the current presidential term in the US. So, what I believe would be extremely important is to maintain almost daily conversations that are government to government, government to government, but especially the most important ones will be business to business, to provide information and hopefully some guardrails around the positions taken.

I think it will be very, very difficult to go back to a time when the US was fully complying with its international commitments, but that’s a battle that we need to pursue every single day. So, I think it’ll be topsy-turvy, hopefully with an upward trend, not like the stock market now, but it’ll be topsy-turvy. That’s the way I see things.

Daniel Batlle:

Well, thank you for a very comprehensive look at things. Luis, we’ve seen increasing concentration of power in Mexico in the presidency, and we now see a new president who seems to have consolidated her position, enjoys immense popularity. At the same time, there’s significant governance challenges from judicial reforms and from a series of other measures. How do you see President Sheinbaum in terms of her ability to manage the challenges that Mexico faces?

Luis Rubio:

Well, we’ve seen enormous concentration of power in Morena. The president controls the administrative structure, but not necessarily power as such. The two big reforms she has sent to Congress were defeated and were changed to the point where they were turned to irrelevance. So, it is Morena that drives everything, and Morena is fragmenting, as it is prone to do. And in the absence of the factor that gave it cohesion, which was López Obrador, that has become the norm.

Fragmentation follows different lines. One very obvious is people who were PRI candidates for the 2030 presidential race, some Morena groups are already forming around that. The other, the more important I think, paradox of all of this is that so much control gives enormous power to the more radical elements of Morena, because they cannot be stopped with the argument that you need to negotiate with an opposition which doesn’t exist.

So, at this point, the negotiations within Morena are the most important ones. This is not a replication of PRI, were there were structures of discipline, where there was much power coming from above. This is a much more fluid situation within Morena, and they are in charge. The opposition is unlikely to come out from its [inaudible 00:28:46] anytime soon. PRI is moving very quickly towards becoming one more green party, meaning that they are going to sell their services in terms of votes to the party in government.

PAN doesn’t have a leadership capable of bringing it out of the situation it’s in, and much of what they are, both those parties’ suffering, comes from the so-called Pact for Mexico that was signed with Peña Nieto in 2013. That was a very deep strategic mistake for both, for PRD and PAN in the opposition and PRI in government. The other party that is around there, small, but a potential alternative, is Movimiento Ciudadano, Citizens’ Movement. They don’t have much of a structure either, but at least they don’t come associated with the old PRI or the old PRI system. But the point is that there’s nobody to catch those opportunities.

President Sheinbaum has been furthermore, working as if she were a surrogate leader rather than a leader in of herself. Whether she eventually breaks away from Lopez Obrador or not is another story. But at this point, she’s basically trying to implement and continue. Her position has been that she is the second floor, meaning the continuation of what Lopez Obrador started.

Daniel Batlle:

We were just discussing the upcoming elections for judges, and just discussing some of the colorful characters running. What can we expect from this process? How do you see this playing out?

Luis Rubio:

Well, that reform, the judicial reform, like all of the other reforms that were carried out in September, were the result of specific grievances or obsessions by Lopez Obrador. He didn’t like the Supreme Court ruling against two of his bills, of his implementing legislation on electricity, and I forget which was the other one. And therefore he wanted to get rid of the Supreme Court. So the question is why did they go after the whole judiciary? But the point is that what he wanted was to replace the Supreme Court. And it’s going to be voted by the people, but voted among candidates that have been filtered by Morena, and therefore the outcome is already pre-established. So I don’t think we can expect much of it. There are some judges that are current judges and are running and may get to be elected, and that may not be too bad. The judiciary was never a source for people to solve and address conflicts. It was never very effective for the average citizen, but this is unlikely to make it any better.

Daniel Batlle:

Okay, thank you. John, you’ve mentioned some of the positive things that the new government is doing, many of them related to building the capacity of the state to confront the cartels, and many of these are things in which traditionally Mexico has cooperated with the United States. Can you describe the way that US-Mexico security cooperation has worked in the past, and do you see any prospects of getting back to a situation where there’s broad cooperation on these issues?

John Creamer:

Okay. No, look, I think in the moments of better cooperation in the past, we’ve seen very extensive sharing of intelligence and information. We’ve seen cooperation on evidence collection investigations, collaboration on extraditions, and visa and financial sanctions. We’ve also seen US assistance programs aimed at capacity building for Mexican institutions, both with training and equipment. The probably golden age of cooperation was under the Merida Initiative in 2007, 2008, which provided some $3.3 billion worth of assistance over a 13-year period. It started under the Calderon administration and then continued into a Pena Nieto before it ran aground with the Lopez Obrador administration. I think that period made some advances, certainly tactical advances in breaking down groups like the Zetas. Obviously did not solve the security problems or the drug trafficking problem confronting the US or the security problems in Mexico. But I think it’s a good starting point to look at renewing cooperation.

I will caution, however, that the cooperation has always suffered ups and downs. I think that largely reflects differences in priorities and strategies. Certainly under President Lopez Obrador reflected some ideological differences. And then further complicating it has been Mexican concerns or sensitivities around its sovereignty, which are rooted in the power asymmetry between the two countries, as well as some of the history of interventions on the US side. And that’s combined with a lack of trust both on the US side. I mentioned a kind of golden era cooperation with Calderon. Of course there’s a big asterisk because the head of the Mexican effort in this, Genaro Garcia Luna is now serving time in a US prison because he was convicted of working with the Sinaloa Cartel the whole time he was leading the Mexican anti-drug effort. So that leads to a fair amount of distrust on the US side. But on the Mexican side, I think mistakenly, but there’s always a suspicion that the US is using some of its prosecutions in a political manner as much as in a security manner.

So all of those suspicions are out there. I do think at this moment, as I mentioned, the Sheinbaum administration is moving to a more aggressive campaign. I think that the selection of Omar Garcia Harfuch and her support for him creates the possibility of greater cooperation with the US. It’s a movement in a direction that we support. He himself worked well with US agencies, both when he was in the Fiscalia and also when he was the police chief in Mexico City. So I think there’s a good basis we’ve seen already even before President Trump was elected, increases in arrests, increases in lab seizures coming out of Mexico.

I think on the US side with the Trump administration certainly conveyed the seriousness with which we are taking the fentanyl issue with the foreign terrorist organization designation of Mexican cartels, with the imposition of tariffs to underscore to the Mexicans that we want to see greater action at this point. And with some of this talk about possible unilateral military action. I think that that has succeeded in moving the Overton window for possible US-Mexico cooperation. The clearest example of that was the Mexican expulsion of 29 long sought after narcotraffickers to the United States on March 1st, basically short-circuited the judicial procedures in Mexico, invoking national security to send them to the US. These included people like Rafael Caro Quintero, who was involved in the murder of the DEA agent. Kiki Camarena back in 1985. Includes Zeta 40, Zeta 42, it’s one of the most violent and largest drug trafficking organizations to the United States. As well as people who have been detained quite recently, Jose Canobbio, who have a lot of current information about the functioning of a narcotrafficking organization. So this really was an unprecedented action. It was quite courageous on her part, and probably would not have happened without some of the pressure from the Trump administration.

My caution is I think that while there’s an opportunity to renew, and perhaps in an even more successful way, all the types of cooperation I’ve talked about, it’s not as if the sensitivities of Mexico on sovereignty and others have completely disappeared, not as if the differences in terms of priorities. Mexican’s priorities has historically been reducing violence while the US is reducing drug flows to the United States. Those two are not necessarily in competition. 60 percent to 65 percent of the homicides in Mexico can be attributed to drug trafficking organizations, but they’re not exactly the same thing. So that creates some difficulties.

And again, there’s that underlying, I think, distrust on both sides. I guess to address that, it’s extremely important for both sides to be as transparent as possible while preserving the integrity of investigations, building the personal relationships across agencies is crucial, and to the extent that we can have certain rules, like the Brownsville letter in 1998, which came out of an earlier conflict between the two countries, to at least establish some parameters which the countries would operate, would go a long way towards creating a basis for sustained viable cooperation down the road.

My concern is that if something like the US discussion of unilateral US action in Mexico went from rhetoric to action, I think that would be incredibly devastating in a negative way towards promoting greater cooperation between the two countries. So I think that we have an opportunity to move forward. The pressure from the Trump administration, again, has moved the Overton window, I think, in terms of what is possible. But if we push that too far, if we cross the line into something like unilateral military action, I think that could be a real setback that would really damage cooperation between the countries for quite some time.

And just close by noting, look, we have one of the world’s largest illicit markets here in North America. It’s an integrated market, unfortunately. You have drugs, unauthorized labor, contraband moving to the US, largely by Mexican organized crime. You have weapons moving from the US down to Mexico. And you have huge amounts of money, the revenues from this both crossing the border and staying in the United States. The only way we can actually effectively deal with this and cut it back is through cooperation between our two countries.

Daniel Batlle:

I think you’ve made some very important points. Thank you. Antonio, coming back to trade and economics, do you see US-Mexico supply chain integration taking a different shape in the future? Or do you think it is on life support right now? How do you see the future of supply chains in US and Mexico?

Antonio Ortiz-Mena:

Okay, let me work on the basis that there will be a certain level of uncertainty over the next couple of years. Hopefully what’s enforced today will be the basis for improvements, but there will be uncertainty.

I believe that a large number of firms will try to stick with their current supply chains, maybe make some modest moves to the US, more for political reasons than from an economic rationale. But just imagine that you move some auto plants from Silao, Guanajuato, to South Carolina because of the current rules on autos that, by the way, are in flux. And then those rules change in the next administration. Then what could have looked like a smart move today will be a very costly move later on. So I think a lot of companies will be very cautious. Maybe they will be making some modest moves, but I think it is not technically and not financially feasible to engage in whole scale change, yes, because of some higher costs in the US, but also because of policy volatility in general.

Some upsetting factors could be lower tax rates in the US, draconian deregulation in the US, but I don’t know if those two policies would offset. And again, I underscore not tariffs, but uncertainty over tariffs. Also, Daniel, I don’t know if we’re in the Smoot-Hawley world, very high level tariffs intended to stay there for a long time, or in the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act, which is where you negotiate bilaterally to reduce tariffs. At some point, from what the US government says, it seems that we are in an RTAA world. Other countries impose tariffs and non-tariff barriers against the US. The US will raise them. The theory is that then those countries would reduce their tariffs and the US would reduce its own tariffs, right? So it would be better off in the medium to long-term. However, sometimes the interpretation is that the tariffs are here long-term because the US wants to industrialize. In Mexico, we are all taught about import substitution, industrialization. That meant permanent high tariffs for a long time, so maybe they won’t come back.

And then a conundrum that I haven’t been able to fully understand is the role that tariffs will play in the US as a source of revenue to offset tax cuts, right? If we follow the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act and the US raises tariffs, other countries reduce them, the US reduces them, then there won’t be a lot of revenues. If on the other hand, you keep tariffs very high to industrialize and to produce internally what you were importing before, well, in theory, a lot of goods won’t be coming into the US, therefore they won’t be paying tariffs, therefore. There won’t be a lot of revenue here. I’m just trying to go through the logic of things that have been announced, and I think that those uncertainties would make companies take pause and take a very cautious approach to any significant change in their supply chain strategy.

Daniel Batlle:

With Chinese investment in Mexico emerging as an issue for the United States, and potentially an obstacle to continuation of USMCA, Mexico has floated the idea of basically matching US tariffs on China. Is that a good idea? Could that provide a foundation for a more productive trade relationship with the United States?

Antonio Ortiz-Mena:

Yeah, I certainly believe that unfair trade from China is a legitimate concern in the US. It has also been a concern in Mexico for many years. In fact, Mexico was one of the last countries that accepted China’s entry, or the last country that accepted China’s entry, into the WTO. In that way, we were ahead of the curve because the US was pushing for entry and Mexico honestly was dragging its feet.

Now, the US alleges that there are some goods that come from China, go to Mexico, and enter the US. I don’t believe that’s the case. I believe that regulations are very clear and supervision and enforcement is very strong. However, if the US is concerned about unfair trade from China, I think it makes eminent sense to coordinate with its two top trade partners, which is number one, Mexico and, number two, Canada. I think that’s important, but even more important, I think that information exchange. . . We’re still debating about the amount and nature of Chinese investment in Mexico, the amount and nature of Chinese investment in the US and in Canada. I think we still need to know what we’re talking about. We’re not there yet.

And then to engage in very deep policy cooperation, in some cases, yes, perhaps trade and investment issues regarding China. One idea that has been floated, and it comes and goes, is to have a common external tariff to turn North America into a customs union. It would mean a deeper integration. You can do away with the rules of origin. It would be much more efficient and transparent. I think that, in theory, in a classroom blackboard, that’s great, but under the current stance to keep a common external tariff, I think Mexico and Canada would, in a way, have to follow the US lead, so we would be in a roller coaster ride. I think, for right now, I don’t like that roller coaster. I’m staying on firm ground here.

Daniel Batlle:

Okay. Great. Luis, with Plan Mexico, Claudia Sheinbaum has at least recognized the importance of the market and of private investment in Mexico’s economy. There’s a slight departure from her predecessor on the role of the market. Do you see that as enough of a shift or is her investment plan going to be not enough for the private sector?

Luis Rubio:

She’s made a dramatic and very significant conceptual shift. She’s mentioning two words that were taboo during Lopez Obrador’s time, and one is economic growth, the other is near-shoring. And when she talks about economic growth, she talks about private investment. The rhetoric is excellent. What there’s very little of is substance behind it. And the reforms that have been introduced, which she continues to support, go counter to the possibility of attracting investment.

And I’d like to put this in the framework of something that John said that I think is. . . I could add an additional element. The drug cartels have become ever more relevant in the Mexico-US relationship. If one thinks in terms of marijuana being exported into the US 30 or 40 years ago, a ton of marijuana could wield, I’m just throwing a number, $100,000. A little bottle of fentanyl or methamphetamines can wield $10 million. It’s a dramatic shift in the nature of the logistics related to this.

But what affects most Mexicans is not drugs, but it’s extortion, kidnapping, stealing of merchandise, people trafficking, some of which gets to the US, but most of that is in pesos. It’s domestic, it’s organized crime. Some of these organizations, I have no idea how many, maybe John has a better idea, some are spin-offs of the drug cartels, but that’s a different element that has to be addressed for the economy to pick up, for Mexicans to live different. Today, Mexicans have normalized that and it’s amazing how that doesn’t cost the government. This government or the previous ones, including those before Lopez Obrador.

Daniel Batlle:

Thank you. We have a bit of time for questions from the audience. There’s a microphone in the back. Eric? Eric.

Eric Farnsworth:

Thanks, Dan. Thanks for putting together this all-star panel. Congratulations to all of you for your excellent comments. Eric Farnsworth with the Council of the Americas.

I want to pick up on the last comments on the economy. One of the continuation in the relationship with US and Mexico, no matter how bad things have gotten over the years, has been the private sector and the private sector doesn’t go away. It tries to adjust and evolve, et cetera, but it’s always been a glue that’s held together the two countries even during difficult times.

And the question I would have is, if you look ahead in terms of USMCA, the tariffs that have been announced have clearly taken account of USMCA. Antonio, you were talking about that, I think very effectively. What does this suggest, if you can read the tea leaves, for USMCA going forward? Is this an agreement that is, as some people have claimed, dead? Is it an agreement that is going to come back in a different form? Where do you see this from the Mexican perspective and with the framework that Lopez Obrador clearly made this a priority to maintain USMCA? In fact, that seemed to be the basis of his relationship or one of the bases with President Trump in the first term. New president in Mexico, same president in the United States, changed global circumstances. How do you see these issues playing out?

Antonio Ortiz-Mena:

Thanks, Eric. I would say that there is a very interesting situation in Mexico. Mexico is politically very, very polarized, just like the US is polarized. And one thing for which there is broad support is the USMCA. In fact, the traditional leftist newspaper, called La Jornada, just put in editorial, “and now we’re defending the USMCA?” They have been bashing it for decades. I think that speaks well about the alignment of economic interests and political interest in Mexico. And that’s something very, very important.

Secondly, related to the question Luis Rubio just addressed about economic development plan and the rules. I think Mexico has the opportunity, or perhaps the challenge, to establish a great deal of clarity to complement uncertainty in the bilateral relation and globally. And in terms of where business to business relations come, I think the most essential policy in economics, I’m not talking here security, is actually energy because there’s a lot of talk about nearshoring or re-shoring or producing jointly with the US and, right now, Mexico’s implementing some legal changes to the generation and distribution of energy.

If I were to look at a one single economic policy in Mexico, that could affect the whole economy, that would be energy. And in fact, I think that some concerns about regulatory bodies might be overblown, just like in the US right now, where a lot of regulatory bodies are being weakened in one way or another. Regulatory bodies in Mexico were, indeed, weakened. They were autonomous. They’re no longer autonomous. What I’m advising companies is to look at what they do. Are they making rules and decisions based on law, on sound economic thinking, et cetera?

Again, I wish they were stronger, more autonomous. But I think that, in the grand scheme of things, that is of lesser concern if, in practice, they do an okay job. It’s a big question mark than the energy. For me, energy is really the crux of what will happen to the Mexican economy and Mexico-US trade and investment relations. Might be an obvious point, but sometimes it gets lost in these very broad discussions, Eric.

Daniel Batlle:

Question here.

Question:

Thank you. Just a question about Mexico’s fiscal situation. As you all know, last year the deficit was 5.7 percent, the largest in decades. This year, we were due for a strong fiscal consolidation, even in good times. And now that a recession is the most likely outcome, spending will have to come down a lot faster. At the same time, the finance ministry still has pretty unrealistic growth projections of 1.5 to 2 percent. My question is, do you all think that President Sheinbaum will be able to bring spending under control? Will she cut spending in the areas that strain the budget most? Pemex and social programs, subsidies, pensions, or will we continue to see budget cuts to other areas, such as health or security, where perhaps the country can no longer afford budget cuts in those areas?

Luis Rubio:

The only thing I’d say is that they are doing a pretty good job about cutting and trying to maintain the budget in check, to the point that they are not doing things that are absolutely necessary because there is no money. Talking about minor amounts. But you’re right in that there are some of the elements in which they are spending, some of the lines of the budget in which they are spending, that are unsustainable. The growth of the social programs is also sustainable with the current level of economic growth and revenue the government gets. That’s true of the spending programs. It’s true even more true of Pemex.

Pemex loses enormous amounts for every barrel that is refined. The quickest way to fix the Pemex situation would be to simply stop refining, but that’s something that is un-Mexican. It’s inconceivable for a government like this. There are solutions, but they are not focusing on them. And I think it’s going to come to a head at some time this year. There are some people who are predicting that Pemex is going to come down in its production levels significantly, later this year, because they’re not paying their suppliers. All of this makes a picture that will require a very different fiscal solution, whether they’ll take it or not, it’s anybody’s guess.

The other element there is, of course, the rating agencies that are hounds around them looking at the numbers and that might also force them to do things that they are not willing to do today. But don’t forget that the great part of the reason why the President is so popular has to do with the cash transfers to their clienteles. That’s why they were untouchable.

Daniel Batlle:

I promised to wrap up at 11. I want to thank our speakers. I think this has been a rich and productive discussion, so thank you very much for your analysis and I want to thank the audience. It’s great to have an engaged audience. I think the theme of this discussion, I think, is uncertainty and I think the need for patience in watching how things play out in Mexico, no easy solutions on the horizon. There’s a lot that bears watching. But again, I appreciate the excellent analysis from our panel today.

Luis Rubio:

Thanks for the opportunity.

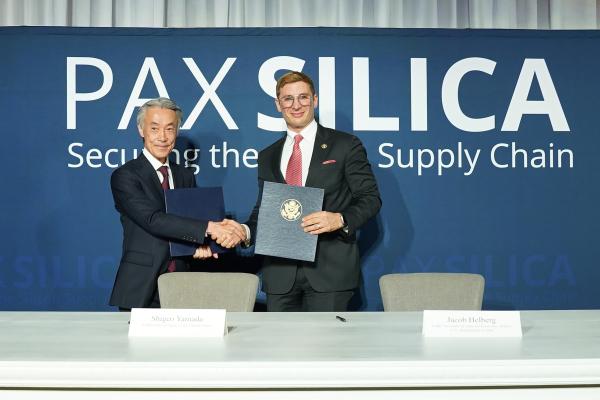

Please join Under Secretary Helberg and Hudson Executive Vice President Joel Scanlon for a discussion on the Pax Silicia initiative, America’s strategy to win the global AI race, and the new geopolitical imperatives of economic security and technology.

Please join Ambassador Greer for a fireside chat with Senior Fellow Peter Rough on the Trump administration’s first year back in office and what’s next for US trade policy.

Hudson welcomes French Army Chief of Staff General Pierre Schill, one of Europe’s most senior military leaders, for a discussion on the evolving strategic environment and the French Army’s transformation in a rapidly changing world.

Join Hudson for a conversation with Assistant Secretary of War for Industrial Base Policy Michael Cadenazzi, who leads the DoW’s efforts to develop and maintain the US defense industrial base to secure critical national security supply chains.