Defense Innovation and the New Cold War

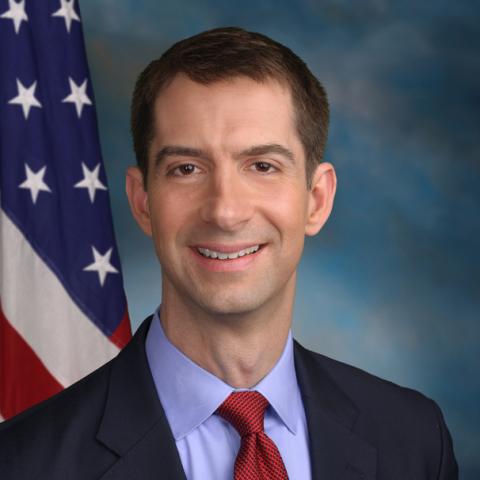

United States Senator, Arkansas

Tom Cotton is a United States senator from Arkansas.

Cofounder, Palantir Technologies

Chief Technology Officer, Palantir Technologies

Senior Fellow

Nadia Schadlow is a senior fellow at Hudson Institute and a co-chair of the Hamilton Commission on Securing America’s National Security Innovation Base.

Senior Fellow, American Enterprise Institute

Budget Director, Senate Armed Services Committee

Senior Fellow and Director, Keystone Defense Initiative

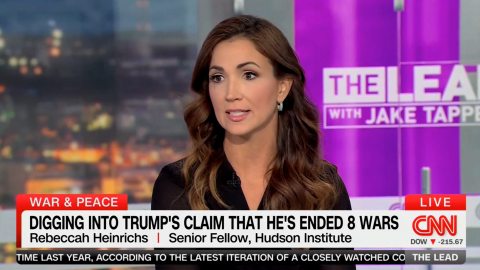

Rebeccah L. Heinrichs is a senior fellow and director of the Keystone Defense Initiative. She specializes in US national defense policy with a focus on strategic deterrence.

Founder, Polaris National Security and Former State Department Spokesperson

Morgan Ortagus is the founder of Polaris National Security. She served as the spokesperson for the State Department under Secretary of State Mike Pompeo.

China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea present a pressing threat to the United States and its allies. Russia’s war against Ukraine seeks to break the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s unity and render US defense commitments unreliable. Iran is waging a proxy war to destroy Israel and force the United States out of the Middle East. And China and North Korea are materially supporting these efforts while menacing their Indo-Pacific neighbors.

This threat environment is teaching American defense planners and policymakers hard lessons about the need to adapt and change the way the United States budgets, tests, acquires, and deploys new and existing weapon systems. Join Hudson for two panels that will discuss these lessons and why Washington urgently needs to apply them.

Program

Introduction

- Rebeccah L. Heinrichs, Senior Fellow and Director, Keystone Defense Initiative, Hudson Institute

Panel 1: Defense Innovation

- Senator Tom Cotton, United States Senator, Arkansas

- Joe Lonsdale, Cofounder, Palantir Technologies

- Shyam Sankar, Chief Technology Officer, Palantir Technologies

- Nadia Schadlow, Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute

Moderator

- Morgan D. Ortagus, Founder, POLARIS National Security

Panel 2: Defense Implementation

- Mackenzie Eaglen, Senior Fellow, American Enterprise Institute

- Richard Berger, Budget Director, Senate Armed Services Committee

- Nadia Schadlow, Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute

Moderator

- Rebeccah L. Heinrichs, Senior Fellow and Director, Keystone Defense Initiative, Hudson Institute

Event Transcript

This transcription is automatically generated and edited lightly for accuracy. Please excuse any errors.

Rebeccah L. Heinrichs:

Good morning. Welcome to this event at Hudson Institute, and welcome to those of you who are joining us online. My name is Rebecca Heinrichs and I am the director of the Keystone Defense Initiative here at Hudson Institute, where I’m also a senior fellow. Here at Hudson we are committed to freedom, security, and prosperity. We’re committed to US leadership abroad so that our allies may enjoy the freedom, security, and prosperity that we do here. It’s my privilege to introduce the distinguished panel we have here today because here at Hudson, we don’t just want to develop good ideas, good policies, but we want to put them into action. And so it’s a real privilege to have men and women of action who are here to talk about how to implement some of these great ideas.

Today we have Senator Tom Cotton, who represents the state of Arkansas in the US Senate where he has served since 2015. In the Senate, Senator Cotton serves on the Senate Armed Services Committee, where he’s the ranking member of the Subcommittee on Air-Land. He also serves on the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence and the Senate Judiciary Committee. Prior to his service in the Senate, Senator Cotton was an infantry officer in the US Army, serving on two combat tours in Iraq and Afghanistan. He also served one term in the US House of Representatives. prior to joining the Senate. He received a Bachelor of Arts, magna cum laude, and a JD from Harvard.

Next to him, Mr. Joe Lonsdale. He’s a technology entrepreneur and investor, currently working as the managing partner for 8VC, a US-based venture capital firm. Mr. Lonsdale cofounded Palantir Technologies, a global software company that has worked extensively in the defense field as well as other industries. He has also been involved in the creation of other growing companies in the defense industry, including as cofounder of Epirus and an early institutional investor in the Anduril Industries. Outside of the defense base, Mr. Lonsdale has been an early investor in several successful tech companies.

Shyam Sankar is currently the chief technology officer and executive vice president of Palantir Technologies. Mr. Sankar has worked for Palantir since 2006, and he has also previously served as the company’s chief operating officer. Mr. Sankar received a bachelor of science in electrical and computer engineering from Cornell University and a master of science in management science and engineering from Stanford University.

And then Hudson’s own Dr. Nadia Schadlow is a senior fellow here at Hudson and cochair of the Hamilton Commission on Securing America’s National Security Innovation Base. Here at Hudson, Dr. Schadlow conducts research analysis on a range of issues at the intersection of strategy, national security and technology. Prior to joining us at Hudson, Dr. Schadlow served as the US deputy national security advisor for strategy, where she led the drafting and publication of the 2017 National Security Strategy.

And then my friend, Morgan D. Ortagus is the founder of Polaris National Security, a nonprofit organization focused on American foreign policy. Ms. Ortagus is also a US naval reserve officer, a general partner at Mare Liberum, a fund focused on maritime sustainability and security. She’s the host of the Morgan Ortagus Show, one of the best shows there is with the most interesting people talking about national security policy, the people who are actually making these decisions, and folks should really tune in.

From 2019 to ’21, Ms. Ortagus was the spokesperson for the US Department of State where she worked closely with the White House on the Abraham Accords and traveled with Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to more than 50 countries. She has also held roles with the US Agency for International Development and the US Treasury. Ms. Ortagus holds a bachelor’s degree in political science from Florida Southern University and a dual MA in government and an MBA from Johns Hopkins University. It’s my pleasure to welcome this distinguished panel, and then I will turn over to Morgan, and then the floor is yours.

Morgan D. Ortagus:

Thank you. Well, thank you, Rebeccah. We’re going to jump right in. Good morning and welcome to everybody who I believe is watching us on the live stream virtually. I agree with Rebecca. You should listen to my show every Sunday on SiriusXM Patriot, Channel 125. I think I bugged the four of you, Joe was just on, to come on the show. It’s good stuff.

Listen, there’s so much going on. We’re going to start with Senator Cotton, of course. I was just at a conference where we were discussing, again, the innovation that we’ve seen in the Ukraine war, but I don’t think it’s talked about enough in the context of what we’ve seen for almost a year with Israel having to face munitions, drones, sophisticated weaponry coming from Iran and from all of their actors around the region. So specifically in the context what Israel’s done in the last two weeks, they’ve made a lot of news, but tell me what you think about how Israel has been able to innovate and change the future of war over the past year since October 7.

Senator Tom Cotton:

Thanks, Morgan for the question. Rebecca and Hudson, thanks for hosting us. I mean, I think it helps that Israel doesn’t have the world’s largest and most complicated bureaucracy, the American Department of Defense in charge of developing some of this new technology. What we’ve seen in Israel for years, but especially over the last couple of weeks, but also what we’ve seen in Ukraine is a couple of things, in my opinion about technology, is it has to change faster and there has to be more innovation.

We still need stealth bombers and fighters and aircraft carriers and submarines, but a lot of what you’ve seen on the battlefield in the Middle East and Ukraine are smaller, more expendable items that have much higher production rates, therefore much lower unit cost as well. So that’s one thing that Israel and Ukraine has done very well that our Department of Defense doesn’t do that well because it doesn’t innovate fast, government as a whole doesn’t really.

The second thing though that I think you should note is that in the end, it’s still battlefield technology that is making the difference. Too many of my colleagues in the Congress think that you can win wars with keyboard strokes or hashtags or lighting up your national symphony with another country’s flag colors. In the end, you win wars by killing the other side’s soldiers or destroying their stuff, whether it’s with a Tomahawk missile or an Abrams tank, or increasingly in the case in of say, Ukraine and Israel with again, small high-production, low-cost drones or munitions. And we have to keep that in mind. That war may change in the technology that’s used, but that’s ultimately the way wars have been fought and won forever, is by closing with and destroying the enemy on the battlefield.

And despite all the technological innovations you’ve seen in Israel and in Ukraine, it’s still Israeli soldiers and Ukrainian soldiers on the front line going door to door or fighting in the trenches, fortunately enabled with much better technology. But for those who would argue that somehow new technology is going to change, fundamentally, the face of war and change that irreducible human aspect, you might be right, I grant you. I have more than 3,000 years of recorded history on my side and untold millennia of prerecorded history. Technology does change, and we need to change a lot faster in the United States like Israel has, like Ukraine increasingly is, to face the threats to America, especially the threat from Chinese communism. But in the end, it’s still going to be battlefield technology that makes the difference.

Morgan D. Ortagus:

So you’re telling me the strongly worded letter from Biden and Macron last night may not do the job?

Senator Tom Cotton:

No, it won’t do the job. I mean, someone blew up a bunch of Hezbollah terrorists using beepers and walkie-talkies. And I would imagine Hezbollah terrorists are very skeptical now about using the cell phones or even the electric toothbrushes they might have. But that’s an example of how, again, whoever was behind that very clever, very cutting-edge technology, getting into supply chains makes you wonder maybe what’s in our supply chain here in America. But in the end, it’s still killing or wounding warriors on the battlefield.

Because terrorist operatives are always on the battlefield, whether they’re in the Beqaa Valley or whether they’re shopping at a fruit stand. I mean, that’s what a terrorist is by definition. This is an asymmetrical weapon against a civilized nation like Israel and the United States. And the people behind that had a masterstroke of technological innovation and operational brilliance, but it was still taking out the other side’s soldiers.

Morgan D. Ortagus:

So Joe, you’re working on everything Senator Cotton just said that we need to do for the future of warfare. So how do you see this playing out in Israel, but specifically, is the US doing enough from an innovation perspective to cooperate with Israel to share new innovations? And if not, what else should we be doing?

Joe Lonsdale:

Well, first of all, when we have a terrorist organization on the run that’s been attacking us in Israel or in our allies in the West for decades, and we’re about to destroy it, we shouldn’t send a strongly word letter to say, stop, don’t destroy us.

Morgan D. Ortagus:

But there’s an election coming.

Joe Lonsdale:

Yeah, well, I think hopefully he loses more from that. But anyway, it’s been amazing, obviously to watch Israel. I agree with the senator, we have to kill the bad guys. But of course, the way we’re learning to kill the bad guys with software combined with the missions is completely different than we’ve ever done before. You’re able to map things out in Ukraine, in Lebanon and other parts of the world in ways we never were able to before. There’s all sorts of technology there that I think they’ve been watching everything Hezbollah has been doing using AI and mapping out any small changes in areas and really figuring out where they all are with all sorts of interesting tactics, and now they’re going to go in and take them out.

And it is absolutely the case. It’s going to be drone warfare, it’s going to be flying drones. There’s going to be autonomous vessels in the water, and then it’s going to be coordinating these at scale with new command and control and new ways that AI and other things are deployed. And it does scare me how far behind the Department of Defense is on these things. A lot of us, the reason we’re starting new companies in these areas, is we know that China is ahead in some of these areas and we want to make sure we stay ahead. And it’s a fascinating time because even the conversations I had with Stafford yesterday asking, is it okay for AI to decide to shoot things or not? It basically misses the entire context.

When you play games, if you haven’t played the game before, you don’t even know how to ask the questions about the strategy for the game. So I think what you need first, for example, is if we have a bunch of talent who have built things like League of Legends and StarCraft, and you put it out there on the battlefield and you assume, for example, you have a battle with China with 6,000 small autonomous vessels that are weaponized alongside ships of the line, and you have the battle and you engage it. And you can show them, well, here’s what happens if you only have to press the button every time it fires, but they don’t. And then here’s, when you turn the dial further and then you do kind of let them fire at will at a certain position, and here’s all the different possibilities.

There’s lots of concepts you can talk about for how you do these battles with software and with AI. And you very quickly realize, wow, all of my assumptions were wrong if I just put a stupid top-down rule because I’m a staffer who’s never played this game before. I’ll destroy us in the battle. So there’s a lot of stuff that I think we really need to kind of show from the tech sector and kind of teach the Navy, teach the DoD, teach Congress, and hopefully get us ahead of China, which is what we’re trying to do right now.

Morgan D. Ortagus:

Yeah, Shyam, as we continue to sort of stay on the Israel beat for just a second, I have to say it was very moving to a lot of us at Palantir last October, whenever you took out the New York Times ad that said that we stand with Israel and your company has been outspoken for the Jewish people and for Israel at a time of rampant, antisemitism in this country. So I’m incredibly appreciative of that.

I want to think about what Israel’s doing as it relates to risk, right? Because they’re willing to make decisions on the battlefield and with their intelligence operations, supply chain operations, psi ops, they’re taking risk on the battlefield that you just are not seeing anywhere else around the world. And I think that we have sort of lost that ability to take that type of risk as the Biden administration tries to do manage escalation, whatever that means. So give me your thoughts on Israel’s risk-taking calculation and what we in the United States could learn from that.

Shyam Sankar:

I think paradoxically, the faster you’re able to innovate on your concepts on your OODA loop, the more risk you can absorb and take. Actually, it’s not that risky to be able to take it. The centralized lesson I take from both Ukraine and Israel is the primacy of winning. To them the only requirement is winning. There’s no requirements to document about building the NGAD. Somehow we’re looking towards a new plane that’s going to cost $300 million per unit instead of a hundred million dollars a unit. But what do we see happening in Ukraine and Israel that actually $20,000 is too expensive and $200 is the right price point. So the whole monopsony is driving us structurally in the wrong direction. And I think what you see with Israel is a whole of nation effort, and I think that allows you to underwrite the risks that you’re going to take as a nation.

And we used to have that. Before the fall of the Berlin Wall, 86 percent of defense spending went to companies that were both commercial and defense. Chrysler made cars, absolutely, but they also made missiles. And Ford made satellites until 1990. And we’ve somehow, having won the Cold War, rotated to this place where we have a coddled and relatively protected industrial base that is not participating in the broader innovation economy that entrepreneurs like Joe are building and funding. And I think this is the moment to kind of fix that and allows us to realize that the things that we perceive as risky are really not.

When we look at Ukraine, we should wonder. Everyone cites that: wow, isn’t it amazing that the Ukrainians took out half the Black Sea fleet even though they don’t have a Navy? And really it’s of course because they don’t have a Navy that they did that. And so how do we bring more of those concepts into what is otherwise a pretty uncompetitive and sclerotic series of institutions that need to challenge these concepts going forward?

Morgan D. Ortagus:

Nadia, when I think about everything that the three of them just said, I think about the United States, we’re really good when we’re punched in the face. When there is a crisis, when there’s a 9/11, even when there’s Covid, I was in the administration Operation Warp Speed, the defense department and other agencies were able to come together and work to build all of these different things that we needed to deal with Covid. So we can innovate, we can be fast, but we tend to only do it when there is some sort of crisis moment. My concern, Nadia, is that when the crisis moment comes with China, it’s going to be too late for us to get in gear.

Nadia Schadlow:

Well, I think the examples that you noted are actually interesting because we do have the tendency and have been somewhat successful with innovating on the outside. DIU, we create external organizations because our bureaucracy is too sclerotic, as Shyam pointed out, to actually innovate within. So we’ve gone from the outside.

Sometimes I actually call it the school choice approach. We can’t fix the public schools, broken. So what did we do? We created schools external to those. And in the same way at DoD, we have examples of DIU, Defense Innovation Unit. We have examples now, our new Replicator in some ways, the Space Force was partly created to do that, the Space Development Agency. We need to now focus on how these organizations are doing. If Replicator fails, which as many of you know it’s DoDs initiative to create thousands of drones cheaper quickly to meet Taiwan Strait situation, if that fails, we actually have almost diminished deterrents actually, because it will really show our adversaries that we really can’t do things. So it’s really important that it succeed, and as patriots here, bipartisan, Replicator needs to succeed.

But having said that, I think one of the themes of all of us this morning is that we need to take an approach of iterative fast innovation, right? Almost I squared. What we are seeing in Israel and in Ukraine is fast innovation at the lower level, at the ground level. We have a tendency in our DoD to think of innovation as almost finished. We’re finished in innovating with this big, big system. Great, we’ve done that. No, it’s this fast cycle of innovation. And I could go on, I have an idea for a congressional report, which I can’t believe I’m going to suggest another one. I’ll wait.

Morgan D. Ortagus:

Senator Cotton. We know that we’re at historic lows on defense spending as it relates to GDP. We know that we’re spending more paying interest on our debt than we are on our defense budget, sadly. And then of course, you look across the Pacific, you see China without going through all the numbers, if you boil it all down, they’re spending a lot more and they’re building a lot more and we can’t keep up. So if those are the hard realities on the ground, how do we deter Xi Jinping from invading Taiwan or from some sort of incident over the second Thomas Shoal?

Senator Tom Cotton:

Yeah, we are spending a lot on our military these days. Unfortunately, if you think it’s expensive to preserve the peace, you should take a look at what it costs to win a war—and, even worse, to lose a war, especially a war over Taiwan. So we need to spend more, but we also need to spend it more efficiently. It’s not just about increasing the top line budget. It’s about doing things that spend that money more effectively.

And obviously a lot of our budget goes to personnel costs of various kinds, like any large organization. Our soldiers have much better lives and get much higher pay, rightly so than a conscript for Chinese communists. But the part of our budget that is spent on procurement and that is spent on R&D could be done a lot better. There’s both improving the production of the things that we already know that we need, as has been proven in Ukraine and Israel. The Department of Defense has made some improvements, but I think there’s a lot more to be done. I think some people are dislocating their shoulder, patting themselves on the back because they’ve got cycle times for pretty basic munitions down from say, 60 months to 24 months. But that’s still not nearly enough.

That is largely just a matter of spending more money, getting more lines open or getting the time that lines are open extended. But then there’s also the investment and those low cost, high production rates, new technologies kind of stuff that Joe and Shyam have been working on and others like them, and making sure that at the same time that we producing the Tomahawks we need or the Javelins that we need, or just the 155 artillery shells that we need, that we’re also investing in the new weapons and the new technologies that are going to make all those older technologies more effective.

And it really is a matter of senior leadership. There’s things we can do in the Congress through the annual defense bill. A year or two ago, we introduced a measure that would require a commercial integration cell in each combatant command. So guys like Joe and Shyam and their companies would hear directly from combatant commanders and troops down on the battlefield what they need and what they need now, as opposed to going through that five-year requirements process, which is not how Ukraine is fighting, not what Israel has always done.

So there’s things we can do, but it really takes senior leadership. And this is what Bob Gates, who I think has been the most successful Secretary of Defense in my adult life, has said is that you go into that job and you have to know there’s a lot of challenges and problems that aren’t going to get fixed no matter how long you’re there. It’s just too big an organization, too bureaucratic, too many problems and challenges, but you have to focus on a few priorities. And only the secretary can do that. He can’t delegate it to the deputy. He’s got to make it a priority. He’s got to break through some of the silos that Nadia talked about and establish working groups and task forces. This is how Bob was able to get mine-resistant, ambush-protected vehicles out to the troops in Iraq and Afghanistan. It’s how he was able to reduce medevac times down to the so-called golden hour, both saved a lot of lives. That really has to be done in the department itself, and I think it needs leadership that is really laser-focused on the speed of innovation.

And one measure would be at the end of administration, do people like Joe and others say, Finally, the Department of Defense is easy to work with? Well, maybe it’ll never be easy to work with, but the Department of Defense has changed and it is much easier to work with. I mean, it’s never going to be quite the same as a business customer of theirs, it’s government, but it’s much easier to work with. We know where to go. We can introduce our technologies and we can get into business with the department and get those technologies in the hands of the men and women on the front lines who need them.

Morgan D. Ortagus:

Just a quick follow-up on that, when you think of the munitions, the 155s, all the sophisticated weaponry, when you talk about the internal at DoD, how much though should we be pushing and depending on our allies? Rahm Emanuel in Japan, for example, has suggested policy changes so that we can build and maintain and repair our ships in theater as opposed to coming back to the United States? Should we be leaning more on allies and partners around the world to help us innovate?

Senator Tom Cotton:

Yeah, I think we have to look at any possible solution because we’re running out of time. We’re running out of time to be ready for a potential conflict over Taiwan and therefore to what our objective should be, which is to deter that conflict from happening in the first place. So I think we have to be creative in our approaches of how we collaborate with trusted allies and ensuring of course, that our supply chains are secure and that we have enough of the stuff that we need without depending on any other country. We need to look to them as potential customers. We need to increase the rate of export of a lot of these, especially basic munitions, because that gives the defense industry the certainty they need to make CAPEX outlays to increase production rates and reduce cycle times and unit costs.

And I think we need to look to at greater use of the Defense Production Act. If you look at just a flow chart of the defense industry and at the top line you may not have that many suppliers who are going directly into the military, but at the second and the third tier, there’s hundreds and hundreds, and a lot of those items have multiple uses, especially basic manufacturing equipment or items. And no offense to any other civilian non-defense industries, but if the defense industry needs something, especially something that’s going to be necessary to deter conflict over Taiwan, I think we have to be willing to consider the DPA to get it to those top tier contractors to make sure they can produce the weapons and the technology that our troops need.

Morgan D. Ortagus:

Joe, you’ve done something a little radical in the United States over your years as a venture capitalist, you’ve sort of made defense investing and working in the defense world cool again. When you think about for a long time, people, their only option was to go to a big prime, and now you are disrupting that space.

But I feel like in the tech world, you’re seeing sort of this extreme ends. We have people like you who are innovating and inspiring young people to work in tech, but then you also have people on the left and other parts of the country that don’t want the technology even used for the defense department, although they’ll use the same technology for the PLA, for an example. So how are you motivating young people to come work for you, and how do you think just the defense tech world in general is doing as it relates to getting young patriots to come do something to better the country?

Joe Lonsdale:

Yeah, and fortunately, I think we are seeing patriots who are on both sides, I think this is a moderate left and right thing, maybe the far left’s against us, but they’re very noisy. But I think most of the talent’s really excited about it. And why does best talent work on something? In the venture capital and the entrepreneurship world I think America is probably number one in this world versus the rest of the world by far. This is our biggest advantage as Americans is we have the best innovation world. And when we see giant gaps, when we see this is possible, but what we have right now is down here, that’s exciting to come work on for the best talent.

You’re working on something that matters because it’s so much better. And this is a really important fact because it ties into everything we’re doing here. If this was just a little better than what the primes were doing or was just a little bit more interesting, no one would be working on it. It wouldn’t be worthwhile. None of these kids would want to do it. The fact is, a lot of this stuff is 10 or a hundred times better per dollar for fighting and stopping the bad guys.

And that’s an important fact, both because it means it’s inspiring to work on, but it also shows how badly our government procurement needs to change and how much you need to put competition into government procurement. Because if you were to allow two different parts of the government that both supposedly had the same mission and similar dollars to compete, and one side was working with the new companies and one side was being safe working with the primes, the side that was being safe would end up looking like crazy people. They’d have 10 times more waste. They get totally defeated. So if we just need to inject a little bit of competition to the government, I think it’d reflect what you’re seeing is that so much better stuff is possible now, that’s coming up and it’s just a fact that I think people in DC don’t fully understand it. It’s a huge difference what we could do here, if we allow that competition and allow these new things in.

Morgan D. Ortagus:

Shyam, China, claims that they are leading the world in advanced AI. They’re loosening their domestic restrictions on development. Where are we in reality? Where is the US-China competition on AI?

Shyam Sankar:

I think America is clearly leading on AI right now, but we cannot rest on our laurels with it. The thing about AI is it is very much an experiential journey. You cannot think your way through it. So the side that is most committed to implementing it, getting reps and sets with it, refining it.

No one wants to be on the self-driving car journey. We had a prototype in 2005. We barely have a commercial service 20 years later. That is very academic. I’d say where we are is we’ve created a magical capability, and now people have to do the hard work of actually seeing whether it’s going to have utility that drives lethality on the battlefield. And this is where we can’t be too mealy-mouthed about it, we have to really get after that problem and try lots of heterodox approaches.

To double down on what Joe was saying, I couldn’t agree more with those comments. But I think the other part of this is what’s kind of unique about the American entrepreneurial spirit that historic and the recent past is concentrated in tech, is that we like heretics, and we used to have these heretics in defense.

Kelly Johnson was a heretic. At 22 he told his boss at Lockheed that the plane was fatally flawed, and 2D diagrams, he redesigned it himself. You think about Edward Hall and how he had to kind of stretch the truth about the ICBM threat from the Soviets in order to get funding for the Minuteman Missile. Everything we’ve done comes from the heretical individuals and the primacy of the individual over the bureaucracy. And that’s what we have in spades with these American heretics who are going out and building companies and leveraging them.

Morgan D. Ortagus:

I love that. Yeah, Nadia, go ahead.

Nadia Schadlow:

Imagine if we ask DoD today, or Congress asks DoD, where are your heretics today? How short would that list be or not? That’s part of the accountability, right? Where are your successes?

Joe Lonsdale:

You have to be a politician to be in charge now, not a politician, sorry.

Nadia Schadlow:

It would be a short report, but it is kind of accountability that we need. And I just wanted to make one comment to your point, Morgan, about allies. Of course, we definitely need allies, but bureaucracy has a way of finding even our allies. It creeps. And so we’re seeing that with AUKUS. AUKUS is three, four years now in making. The ability to cooperate, it’s being hampered by all of our own bureaucracies mixed in with their bureaucracies. So we need an operational concept for working with allies that actually works because to use the same analogy, a failure of AUKUS, a failure of Pillar Two, which is the tech cooperation between the US, UK, and Australia, again, diminishes deterrence. And China’s watching.

Morgan D. Ortagus:

Yeah. We should be able to build the submarines that we commit to in those deals, or it’s just another empty paper bag that doesn’t scare the Chinese.

Joe Lonsdale:

Can I just say on ITAR, I think a lot of people don’t realize the incentives of the big companies. So what’ll happen is we’ll create a new capability and you’re struggling to survive as a startup company such as Epirus, which is able to shoot down swarms of drones. And the King of Jordan will come and visit, and UAE will come and visit and they say, “Se want this. Can we buy this?” And the ITAR rule says no. And then what’ll happen is a big deal will happen with ITAR, with an official Defense Department deal, that’ll have the primes thing, which is much worse, be sold. So you’re blocked from selling as a new company. And then ITAR is used to only sell the big company stuff. And so people don’t realize the reason a lot of these things persist is because the incentive of large companies to lobby and to push in lots of ways for them to persist to smash the small guys. And so we really have to fix that, I think, if you want these innovators to be able to compete.

Shyam Sankar:

I think it has even broader implications on American prosperity. General Atomics on their own dime invented the drone. It is an American birthright, but because FAA wanted to regulate the on-line-of-site operations, and the DoD viewed it as essentially munition, they ITAR controlled it. DJI should not exist. The consumer drone market should be an American prosperous economic initiative to the world.

Morgan D. Ortagus:

Senator Cotton, we all remember in this room, I’m sure everyone’s followed this, in the nineties, the famous Last Supper Dinner, which sort of brought us where we were from a defense prime perspective. If you were to redo the Last Supper Dinner in 2024, what would you tell all the defense companies now?

Senator Tom Cotton:

Well, I do want to say the consolidation and contraction of our defense industry in the 1990s will be a key chapter if in 25 or 50 or 100 years from now, there’s a book written on how the sun set on American power. It probably won’t be this or that vote in the Congress, although there may be one or two related to China. But in the same way that you look back now and how we got to World War II, when you start with new Versailles and how Woodrow Wilson was so stubborn and ideological. But there’s a long series of steps, the Ruhr crisis and the Locarno Agreements, well before Anschluss and Munich. And I think the consolidation and contraction of the defense industry in the 1990s on the assumption that history had ended and they were no longer going to have to fight wars will be a key chapter if that book is ever written, which I hope it won’t be.

But one way to ensure that it won’t be is to talk to our defense industry, not just the primes, but all the people who want to break in and do great work for our troops, and make clear what our expectations are. Look, the primes are not going to go away and they produce a lot of important things, but what Joe said is a great example of it. You can’t have them using the bureaucracy that in many cases they’ve developed together with the Department of Defense to try to exclude rising competition. Competition is good for everyone to include defense primes. I was speaking recently to an entrepreneur who sold his company to a small company. He had a dual-use technology. Turned out the military was using a lot more than it was being used in the civilian world. And he was basically told, you’re a program of record. You either need to go into a JV with a prime or sell to a prime.

And he said he looked into the JV and it’s like, that’s almost just selling to them. So I’m just going to sell to them and get the money out and focus on another line of business, which is too bad because he and his people should have been continuing in the defense industry. And at the New Last Supper, I guess you’d call it, that business has to change and it is going to change. And again, a good measure of it are folks like Joe and Palantir and other companies, do they feel like they’re getting a fair shake? And are we moving faster and are we getting that technology into the hands of the people that needs it? And so much of it is bureaucracy.

I mean, look at how much this country has created in just the last 25 or 30 years. Compare our biggest Fortune 25, Fortune 50 companies, not just defense companies, but companies as a whole to where it was in the 1980s. It’s a radically different list. A lot of the companies on the list today didn’t even exist compared it to Europe. It’s basically the same list because there’s very little innovation in Europe. So it’s working in every other sector of our economy, yet it doesn’t work in the Department of Defense. Why is that?

That’s not because of industry or entrepreneurs. It’s because of our government and bureaucracy. I mean, there’s that little bridge on G.W. Parkway right in front of the Pentagon. I think it probably has a formal name. I think most people call it the Humpback Bridge. Little Stone Bridge. If you’ve driven on the G.W. Parkway, you’ve driven over it. You can see the Pentagon from it. It took longer for the federal government to repair that bridge a few years ago. Just repair it, not build it. And it’s tiny too. It’s like the size of this room. Repair that bridge than it took them to build the entire Pentagon during World War II. Something’s wrong with that picture and that’s what needs to change. So, again, there’s problems with our defense crimes, but I think the department should look inward as much as it looks outward.

Morgan D. Ortagus:

Joe, Senator Cotton can’t pick winners and losers in the defense space and companies, but that’s what you and I do as venture capitalists. I love your Rebel Alliance of companies that you were developing. I love that name for it. And I know we have a lot of young people from universities and people around the country that want to get into defense VC. So tell us a little bit more about what is your Rebel Alliance and how do you make those key investment decisions for which tech you’re going to bet on?

Joe Lonsdale:

Yeah, what we’re doing, I’m only involved in really a handful of companies and the question is what are the biggest gaps for America? And then how can we bring the very, very best talent to bear on it? So I think Palantir in some ways was a very unnatural company to build and in some ways is the first new prime to emerge after that consolidation, which was very, very hard, obviously. It took a lot of persistence, a lot of unfair treatment that we overcame. And the reason we were able to overcome it is because we were ranked number one in Silicon Valley for talent. We literally had hundreds of the most talented software engineers in the country working together persistently who are passionate about the mission. And so similarly, if we’re going to fix the Navy and we want to help them build thousands of small autonomous vessels and teach them how to use AI, that requires a huge number of top talent, both from advanced manufacturing, people who have been at SpaceX and Tesla, as well as people who understand how to weaponize these vessels.

And so you need dozens of the very top people together and you need to raise hundreds of millions of dollars to win there, which is what we’ve done. Or with Epirus, similarly, we need the top talent, the new electronic warfare in certain ways. So actually there is certain talent within places like Raytheon and L3 for certain parts of the systems. But then we also needed the very best Silicon Valley talent to use the new AI chips to get the power to hit on the smaller timescales and to outperform the primes by 10x, which we’ve done there. So what we’re doing is we’re looking at what are the areas that we know are going to be determinative for warfare, determinative for deterrent adversaries, and then how do we put the very best and brightest into these things? And I think it’d be possible if the Pentagon was run by more talented people, that they were doing this instead of me, but they don’t talk to me and get my advice, so I just do it outside of it and then try to convince them the way it works.

Morgan D. Ortagus:

It’s probably a better way to go. Palantir has become quietly famous for a practice that you guys do of embedding programmers in with the war fighters, embedding programmers on the battlefield. Explain to us why that is such a different move compared to some of your competitors and how effective that move has been.

Shyam Sankar:

Well, it’s the anti-playbook. VCs hate it because it seems like it’s never going to scale. What are you doing? This seems like services, not product. But what it misses is you’re not going to have your good idea eating strawberries in Palo Alto. You’re going to learn that on the factory floors of Detroit or in the fire cells of Djibouti. And you need to go observe the empirical gaps that exist. If it could have been solved through a requirements document, it would’ve been solved. So everything deductive and top-down is what the system is built for, which is actually a very unnatural way for an American to operate. We are improvisational and creative. That’s our strength. That’s our culture. So how do you get the talent right next to the problem so that they can hold themselves accountable to shipping lethality every single night?

And if you do that long enough, that gap really compounds and you start to see the war fighters then come to appreciate that, oh, this software is a malleable weapon system. It’s actually my most malleable weapon system. When we were helping execute the Afghan NEO, we shipped 90,000 software updates a week. When we were doing the Afghan NEO, we didn’t freeze the software saying, “Hey, we’re in crisis. We need stability.” We actually accelerated the amount of change to make the software responsive to what the war fighters needed to execute something within a 24-hour window.

Morgan D. Ortagus:

That’s amazing. Nadia, you’re one of the few people in Washington, whenever I read a recent op-ed or something, long-form publication that you’ve done, I learn something. And that’s unfortunately not always the case in D.C., but I was reading about what you call the crisis of repetition where defense strategies are often recycled, but then the leaders are looking for new recommendations and new strategies without looking to the old ones. Tell us a little bit more about what you meant by the crisis of repetition.

Nadia Schadlow:

Thanks, Morgan. I’ve used one example, but unfortunately I could have chosen many and I still might do that in the future. I used one example of critical minerals. So over the past few years, it’s become commonplace to say, “Gee, the United States is vulnerable. We’re vulnerable to critical minerals, single-source suppliers, China.” And I went back and started to look at, gee, well, we were actually saying this 10 years ago. We were actually saying this 20 years ago, 30 years ago. Then I went back to 1980 and I probably could have even gotten back to ’78 to identify DoD documents, reports to Congress, where we identified that vulnerability a long time ago. And I started to think, well, why is this? Is it something major bureaucratic? In fact, my first efforts to get it published were rejected. War on the Rocks rejected it actually, so I still have a little chip on my shoulder.

They rejected it because they said, “Oh no, Nadia, there must be a reason for this. There’s something bureaucratic here.” And no, there really isn’t. It’s about leadership. It’s about a new administration coming in and thinking they just always want the good ideas. And sometimes there’s a reluctance to look back because it’s not as sexy to look back and say, “Oh, what obstacles do we have here? Why did the previous administrations fail at this?” And I think that’s partly a partisan idea too. And it’s both sides. Trump’s executive orders on AI, Biden’s executive orders on AI. My sense is they’re not actually looking at each other’s executive orders and what’s working, what hasn’t worked. So we need to be better about that. Anyone coming into a new administration actually needs to start to look at why the previous efforts to solve a problem failed. You need to begin with failure and then work forward from there.

Morgan D. Ortagus:

Well, unfortunately, there’s a lot of failure to look for.

Nadia Schadlow:

There’s a lot that they can look at.

Morgan D. Ortagus:

We will definitely have our hands full with that. Senator Cotton, when you look at what I call the new quartet of evil, China, Russia, Iran, DPRK, they’ve developed this supply chain of terror where they’re able to resupply themselves from munitions, drones, all the sophisticated hardware that we talked about today. I don’t really see us in the United States doing anything to really interdict that supply chain of terror. What more can and should we be doing?

Senator Tom Cotton:

Someone interdicted it going into Lebanon recently. Yeah, I think that we have to recognize that these countries really do form a de facto axis. They don’t need formal alliance agreements. They don’t need a Molotov-Ribbentrop pact. They can look at what’s happening with each other and act opportunistically. And sometimes it is more formal. A no-limits partnership between Russia and China and how much China is aiding Russia’s war in Ukraine, crossing a red line that Biden had drawn, and there’s been no consequences imposed. Now North Korea and Iran aiding Russia as well, and Russia of course, reciprocating in various ways. I think we need to recognize that the Biden administration’s approach that, oh, we can seal off and compartmentalize a conflict in one place of the world is faulty, and that’s not the way our adversaries look at us, especially when it’s a question of American political will.

If we falter or blink in one place of the world, it makes it more likely we will in another place of the world. And that one way to exhibit our will is to be much more forceful on the kinds of cooperation that we can stop, whether it’s through the use of sanctions or through diplomatic and political pressure or financial pressure, what have you. But right now, this administration, as you’ve implied and others have as well, is so scared of its own shadow, at any threat of escalation, they in a way encourage all of these countries to escalate not just in their own theater, fighting their own distinct war, but across theaters helping each other as well.

Morgan D. Ortagus:

Yeah, totally. Joe, I’m going to admit something really dorky. I have a Google alert set up for you because I always find that I learn something in your interviews, and also being in the VC defense space, I want to know what you’re doing because you guys are on the cutting edge. So I was watching your CNBC interview the other day when you were talking about. . . I really do have the Google alert. I’m not kidding. Come on, we got to laugh. It was a good joke. I know it’s early. We’ll get some more coffee. But in your CNBC interview, I thought it was really fascinating how you were talking about that Palantir when you founded it wouldn’t have existed and wouldn’t have been able to survive and exist and thrive in Europe because of all of the intense regulations. And I think you also mentioned that it was very difficult in New York state as well, and that’s one of the reasons you guys had to move. So when you think about the regulations and the things in America that are still stifling defense tech, what is it and what needs to move?

Joe Lonsdale:

Yeah, what I was talking about there as well is that Eliot Spitzer came very close to destroying PayPal. He kept trying multiple times.

Morgan D. Ortagus:

Oh, PayPal. Yeah.

Joe Lonsdale:

But Palantir wouldn’t have existed if he had succeeded, and Tesla and SpaceX wouldn’t have succeeded. And frankly, I don’t know if we’d be ahead of China in a lot of these areas if he had succeeded. And that’s exactly what happened in Europe. Europe did have competitors to us that were wiped out because the regulators were just a little bit more powerful, a little bit more bold. And so it actually really matters to boldly push back on the regulatory state. I have an advantage now because I’ve already been successful that I can overcome the tens of millions of dollars of legal costs they sometimes put in the way when you’re trying to start these things. Or I can overcome the 6-month or 12-month delays and harassment from the regulatory state. So in my case, I could see how as you become a billionaire or whatever, for lack of a better word, you do now have an unfair advantage with the regulatory state existing because it can’t really stop you as well.

You could just spend the money and the time and overcome it, but it’s usually unfair to all the other entrepreneurs starting out. I do think it’s a lot harder now that it was 20 years ago in a lot of these areas with these rules. So I think our country’s lacking moral clarity on these things. It’s actually bad for America, it’s bad for everyone, to have a large sprawl of regulatory state. We’re facing around the world, as you talked about, the quartet. I think the threat to use moral clarity is very clear. It’s a communist threat and it’s an Islamist threat. The radical Islamist. And those two things are very strong and they’re very powerful, and they’re going to be a clear threat to us for the next few decades. And if we’re going to win, we have to re-embrace the values that made America a superior civilization, which is our founding values, which includes liberty and not having these people harassing us and ruining things.

Morgan D. Ortagus:

I’m getting the hook but Shyam, I want to ask you the last question. You’ve got a great Substack column called First Breakfast. Similar to what I asked Senator Cotton, if you could have a first breakfast with senators and government leaders, what would you tell them?

Shyam Sankar:

That everyone has given up on communism, including the Russians and the Chinese, except for Cuba and the DoD. And the root of what ails us is monopsony. It’s not the primes. The primes are absolutely part of the solution here. They’ve just said yes to what their one customer has asked for the better part of three decades. And what we need is not a defense industrial base, but an American industrial base. I want all of Tesla’s advanced manufacturing capabilities to benefit and add lethality to the warfighter. And let’s not forget that’s exactly what our adversary is doing. Only 30 to 40 percent of Chinese prime’s revenue comes from the PLA. So that cheap toaster your neighbor bought on Amazon is subsidizing lethality against US service members. It is a whole-of-nation effort, and we got to get back to that. That’s how we won the Cold War. That’s how we’ll win this one.

Morgan D. Ortagus:

Well, as the Jewish lady, I’ll just say amen and hallelujah. So thank you so much, Rebeccah. Thank you, Hudson. Thanks for everybody for listening.

Shyam Sankar:

Thank you.

Rebeccah L. Heinrichs:

Thank you. Again. I’m the Director of our Keystone Defense Initiative here at Hudson Institute. And for those of you just joining us now, this is the second panel in a two-part panel considering the topic of defense innovation and winning the new cold war. The first panel discussed quite a bit about the nature of innovation and how we need to move faster and adapt on the battlefield to stay ahead of our adversaries and to be nimble and to use our advantages as Americans to innovate and be creative and come up with solutions. This next panel is a panel of experts, friends of mine I’m thrilled to have here with me. We are going to discuss how to implement some of these ideas. And then we’re also going to just piggyback off of some of the discussion we had from the first panel, perhaps dissent a little bit, agree, add some more nuance. And so that’s the plan here, and we will have a little bit more time at the end built in for questions from the audience, so please feel free to do that.

Directly to my left is Mackenzie Eaglen. She’s a senior fellow at American Enterprise Institute where she works in defense strategy, defense budgets, military readiness. Ms. Eaglen is also a member of the congressionally established commission on the future of the Navy and a member of the US Army War College Board of Visitors. She’s previously been a staff member on congressionally mandated bipartisan defense review groups in 2010, 2014, and 2018, and she has previously worked on defense issues in the US House of Representatives, the Senate and DoD, and the Heritage Foundation. She holds a bachelor of arts from Mercer University, a master of arts from Georgetown University’s Walsh School of Foreign Service.

Richard Berger is the budget director of the US Senate Armed Services Committee, a position he has held since 2019. Previously, Rich has held roles with the Senate Budget Committee, the American Enterprise Institute, and that’s the end of my sheet, but thrilled to have him here. And he is really going to walk through a lot of what Senator Wicker has planned for us in this Peace Through Strength Initiative, so thrilled to have him here. And then we already introduced my friend Dr. Nadia Schadlow, so I’m not going to go over her bio. You can see it there. But she is here at Hudson, a senior fellow and cochair of the Hamilton Commission on Securing America’s National Security Innovation Base, so thrilled to have the three of you here.

I’m going to start with Mackenzie, and just zoom out and tell us how we’re doing versus China and some of these key areas. We have some great literature that we set out here at Hudson also, including a couple pieces from Mackenzie, so please do check those out whenever you head out today.

Mackenzie Eaglen:

Thanks, great to be here and with all of you who are friends of a very long time. I was appreciative of the optimism on where we are with AI relative to China and the CCP on the last panel, but when I look across the spectrum of national security capabilities and hard power specifically, we’re increasingly falling behind. And in some cases, we’re just plain behind. I think we can lull ourselves in a complacency in DC thinking, well, we’re the best, so we’ll stay the best. We’re innovative. We’re entrepreneurial. We’ve always been in front of the rest with precision munitions, with stealth, with the capabilities that have gotten us to this moment. And we aren’t number one. We aren’t in the driver’s seat in developing cutting-edge capabilities, but particularly I care about conventional forces. I’d love you to talk about our nuclear deterrent and how we’re falling behind there as well.

But conventionally speaking, the balance of power is shifting away from America in all three theaters of the world that matter across Eurasia and the Middle East, and that’s partly because our conventional deterrent is incredible, but we’re not there because the military’s so small, and they’re so small because we’re not keeping up. We’re not replacing the fleets and inventories of the services on a one-for-one, much less a five-to-one, basis. And so while we can have tremendous innovation and incredible inventions of the kind that we’re talking about on the last panel, at the end of the day, the military should be forward. You can’t get in the mind of the bad guy with your virtual presence. That’s just physical absence. And so increasingly, we’re not there. When we need to surge in the Middle East, we take a carrier out of the Pacific. Who wants to do that? But that’s the zero-sum game that we’re in with our conventional forces and our conventional deterrent, so I’m pretty worried.

Rebeccah L. Heinrichs:

Go ahead, Nadia. Do you have—

Nadia Schadlow:

Well, I think a concept that one of my colleagues here at Hudson has advanced, Mike Moran, has a great essay that we’re facing both Star Wars and Mad Max. This sense of the need to both have technical capabilities and a need to also fight wars in the ways that you can hold territory. You need stuff, you need capacity, to Mackenzie’s point, so I always like that analogy.

Rebeccah L. Heinrichs:

Okay, so let’s piggyback off that because the previous panel focused a lot on software innovation changes and all that’s really good. We need to be able to adapt quicker on the battlefield I think is the point, especially about how you’ve got really smart folks making software adaptations quickly to help. But what about this? Larger munitions, larger delivery systems. We’re not going to do away with that and substitute it with . . .

Mackenzie Eaglen:

I was leaning over, coming out of my chair in the last panel. We can all jump all over the primes, I guess. But I was touring a shipyard yesterday. There are 12 naval nuclear reactor cores in the shipyard. This is a very unique capability. Munitions blowing things up on a global scale. The pie should expand. It’s not Palantir versus the primes. There’s enough work for everyone. There’s enough catching up that we need to do for everyone. And there are unique things that the primes do that we will always need them to continue to do, like build nuclear-powered aircraft carriers and submarines, for example. But software’s not a virus. It’s not airborne. And I think that’s what everyone in Washington seems to forget. Well, software will solve a problem. Your software goes in the phone, it’s on the screen, it’s in the chip, it’s on the truck, it’s in the airplane.

You need both. And so this notion that one of the panelists talked about NGAD. Okay, the Air Force has basically said, “We’re out of the global air superiority game because we don’t have enough stuff, so we’re going to do localized, regionalized air superiority pop-up shops, if you will, whenever we can,” because they don’t have enough planes. Now, is everything vulnerable in a peer competition? Absolutely. But everything is vulnerable. It’s not this capability, so therefore we shouldn’t buy the aircraft carrier because it’s vulnerable in war, for example. We have Marines that can’t do NEOs out of Sudan or Syria because there’s no amphibs. So just this notion that we can get by with more software and that alone will solve the problem, to me, is dangerous actually.

Rebeccah L. Heinrichs:

And just to point out too, Shyam has a great piece that we have out there on the literature table that he actually published in War in the Rocks. Sorry. Sorry. Nadia, don’t jump on my shoulder about that. They took his piece. But his point though was that a lot of these companies, he’s talking about Palantir, they will be successful when these primes are more successful too. So it’s a really interesting piece where he says they can’t be in competition. We need the primes to work and be faster and actually just have the ability to take greater risk and operate more like some of these other companies. So I encourage you to read that. All right, Rick, so let’s talk about Senator Wicker’s plan. Nadia just mentioned that we’re going to have to be smarter, we’ve got to spend better, but we’re not going to be able to do this on the cheap. It’s going to require a lot more money too. Can you talk about the Senator’s plan for that?

Richard Berger:

Sure, and thanks for having me. I would go back to, again, what Mackenzie just brought up and what I thought Senator Cotton articulated well on the first panel. Everybody’s learning different lessons from the war in Ukraine as well as from the conflict in the Middle East. Some of those lessons are going to be right, some of them are going to be wrong. People are overgeneralizing about Ukraine. And the weird thing about it, as Senator Cotton mentioned, is you have this very industrial-era portion of the war where we need to build much more 155 armor, protected vehicles, logistics. And then on the flip side, you have new ways of doing business, the resurgence of electronic warfare, of small UAS. And people are learning that no matter what you pick, whether it’s traditional production or innovative approaches, the adversary gets to come up with a counter to everything, so the cycles are getting much smaller.

When Senator Wicker wrote his plan earlier this year, the way that he’s thinking about this is that our relative level of effort, particularly against China and the Western Pacific, is still too low. And part of that is the choices that we’ve made in programs. Part of that is focus and prioritization within the Pentagon. But it’s very clear, Mackenzie has written a great, there’s some others who have done great work on how much the Chinese are spending. It’s far more than the official gut US government experts say it is. Senator Sullivan spoke about this last year. And they’re focused on one part of the world. It just so happens that that part of the world is the future of the global economy, and we are still defending global interest. So we can’t just focus everything at INDOPACOM. So there’s no way to do this without more money. And that’s why Senator Wicker released his plan. At the same time, I think one of the false dichotomies that we see in national security policy is that flat budgets or declining budgets forces people to prioritize to make better choices. If you look back at the 2010s under the Budget Control Act, a bipartisan basket of fun that we went through, again, all the things that Joe and Shyam and Senator Cotton were talking about didn’t exist. It’s very hard to do things innovatively if you have the primes versus these innovative companies, if you have innovative military organizations against the more traditional ones. If everybody’s fighting for the scraps at the table, that is all the Pentagon is consumed with.

And we watched that year after year. People spend a lot more time fighting for a shrinking pie. So I actually think the budget increases that we’ve managed to achieve through Congress in the past few years, with some exceptions, have led to the political and the bureaucratic space for the growth of things like DIU, like RDER, like Replicator, things that still need to be scaled. But you got to push both of these levers at the same time. And that’s the difficulty, is there is no one place in the Pentagon other than the Deputy Secretary of Defense where this all comes together. And so you have people off doing industrial-era warfare, people doing innovation, and there’s not a ton of coordination between them. But the central thesis of his paper is that we need to spend more on its own merits, but also spending more helps you innovate, it helps build the space to innovate.

I think the evidence bears that out over the past few years, and it’s going to be a combination of these approaches and it won’t always stay the same. There may be places where with CCA we’re going to replace fighter aircraft, and then we may find out that actually a counter to that makes it irrelevant if the Chinese figure out an EW approach to get after that. So we’ve got to do both at the same time. And his plan is really focused on the first thing that Senator Cotton said, which is while we’re spending a lot in the military today, the cost of either a deterrence failure vis-a-vis China or losing that war is momentous. It will change the way that the 21st century looks like for Americans, for our children and grandchildren. And that’s not something that anybody wants to see.

Mackenzie Eaglen:

Right. Sure. But we can all foot stomp, an ounce of deterrence is so much cheaper than a pound of war. Amen. But I would just say the embryo of the counterweapon of every single weapon in the United States military will ever build is at the birth of every original weapon. It’s just that’s the way that it works. It doesn’t mean we shouldn’t do it. Just because there might be a counter to CCA in a year doesn’t mean we shouldn’t do it, because inside of the cycle of the innovation and the building and the scaling of production and adding surge capacity, all of these other spin-off benefits come to fruition.

Nadia Schadlow:

Can I ask, I have the tendency to be the creeping moderator, so I’m asking a question. I learned something from Mackenzie a long time ago. Well, I learned a lot from Mackenzie, but I remember once you did this great chart and you actually showed how little of the defense budget is actually malleable, right?

Mackenzie Eaglen:

Yeah.

Nadia Schadlow:

But to Rick’s point, how much of that defense budget and that pie can we actually change to deal with some of the problems here?

Mackenzie Eaglen:

Yes. I call it the paradox of scarcity in the defense budget of largesse. It’s too easy to say, “Well, we spend 815 billion. Isn’t that enough?” It’s an eye-watering amount of money to be sure. But the people who come in and believe that they can then take from this pot and put it over here to a strategic leader wants, I’m going to pivot to Asia for example. We’re still waiting on the pivot, right? We’re still waiting on more resources, manifestly significantly more, 15 years, okay, 13 after the pivot was announced, give or take. And that’s partly because of this paradox. There is a lot of money, but most of it is fenced, it’s fixed. It’s essentially sequestered for other people’s priorities. Everyone’s got their hand in the pot, from appropriators, to the Secretary of Defense’s office, to members of Congress and their earmarks, which is fine. I’m actually very pro earmark. But most of the money is on autopilot.

And so the amount that you can actually get in there and change and move around is, the wedge is probably, it changes by year, but it’s 5 percent to maybe best case scenario, 10 percent of the budget. Reform, spend it smarter, do it better. That is important. But I have not seen anyone, particularly at the most senior levels of the department, this makes the money even harder to get it, and then therefore smaller, the pot that you can actually adjust and move around and put towards other priorities. Defense reform is the patient work of many years, and you have to build coalitions, be bipartisan, answer tough questions, take on sacred cows and important constituencies. Who’s going to take on the military retirees and the veterans?

Okay. That’s how you’re going to get at some of the money, if you’re working with groups like that who you can bring them on board, but no one’s going to do that. So again, that just fences off the funds and it creates a budget that is, like I said, essentially on autopilot. To do great and creative things, to Rick’s point and the senator’s point, you have to be additive. There’s really no scenario. The Budget Control Act resulted in just an older, less capable aging military. It didn’t give us this innovation that everybody wants. You have to provide additional resources unless you’re going to take on and gore sacred cows.

Rebeccah L. Heinrichs:

Two reports recently came out, piggybacking on your comment about bipartisan work, two bipartisan congressionally mandated reports came out the National Defense Strategy Commission, and then the one that I was served on, which was the Strategic Posture Commission. Both of those consensus documents, bipartisan consensus documents came to similar alarming conclusions, which is that we have this growing collaboration between the PRC and the Russians and the North Koreans and the Iranians and the United States, our military is not sized, nor is it ready to deter both of those countries from their revanchist aims and they’re targeting US alliances and our core interests.

So my question is, and then that to me is where Senator Wicker then comes up with his plans. This is where our national interests are, and therefore our strategy has to be based on those interests. And this is just what the budget looks like. So Rick, I guess my question, and for the other two panelists as well, I mean, do think that how much more do we. . . How do we get there to the point where we have Congress aware of the threat? And maybe we are, maybe these reports have helped? Are we on the same page yet about the nature of the threat and what our core interests are and need to defend them?

Richard Berger:

Increasingly, but I don’t think we’re quite there yet. I think actually both parties agree, there’s a pretty good bipartisan consensus about what we want the future of America to look like. Increased standard of living in a sentence, more opportunities for Americans. People are realizing that the axis of aggressors or “The quartet of evil.” As Morgan called them, are working together more closely than ever. But at some point, we really do need a realization throughout the American populace, and this takes a lot of leadership, takes good fiction work too. If you want to look at what a CCP-dominated globe looks like in 2075, somebody needs to write that book. This is the call to the world for if anybody knows anybody. But if you watch The Man in the High Castle, for instance, it’s a very jarring historical look at what America would’ve looked like if the Nazis and the Imperial Japanese had won.

So that’s the future we’re trying to avoid. There’s bipartisan recognition, I think particularly behind closed doors, but we’re still sort of stuck in a structural American politics that is stifling some of that. Almost all the best stuff we do in Congress is bipartisan. There’s no other way to do it. I mean, that’s a feature, not a bug of the Senate. But yeah, at the end of the day, there are light bulbs going off all the time, more and more every day.

But at some point, we really need to think about if we were sitting here five years and we appointed people to be commissioners on the commission about how we lost the war, I’m stealing this from someone. I’m not going to say who, it’s not my idea. We need to be thinking about what would we change today to avoid that outcome? And we’re still not ready to gore some of those sacred cows. Some of them are in the Department of Defense, some of them are in the White House of either party. Some of them are in Congress, some of them are in industry, whether primes or in innovators. So we’re not quite there yet.

Rebeccah L. Heinrichs:

So I’m going to turn in Nadia. She wants to jump in here, but I’m going to give you just a heads-up because the next question I’m going to ask you is just I want to talk about, and you can speak for yourself or you can articulate the Senators use however you want to do that. But the question about then you have to have a strategy. So we have to be able to project power forward. And so I want to talk about what we can do with the Australians, and there’s a reason for that. But in particular, how can we be collaborating with the Australians from a forward force posture? And you can talk about AUKUS, how we want to do that. But Nadia, I wanted—

Nadia Schadlow:

Well, it actually ties in a way. So I was going to make an overall observation, where I’m not sure that we agree across the board, whether bipartisan or even within the Republican Party, on how do we want to look at regional balances of power? How do we think about regional balances of power? Because ultimately that’s how we project power from regions of the world. How do we create balances of power in Asia, in the Middle East, in Europe and ensure that one power doesn’t dominate? What does it mean to do that? What are the tools we have? Do you need American leadership to do that? What are the roles of allies and partners? So to me, that’s implicit in both of the reports that Rebecca discussed, because depending upon how you feel about that, you’ll have a different set of capabilities, tools, and policies.

Rebeccah L. Heinrichs:

The reason I bring up Australia too is because to Rick’s point about you need a little bit of an imagination about what this world will be like with a PRC-dominated world in collaboration with the Russians and the Iranians and North Koreans, but the Australians I look at to see how the PRC treats the Australians. And you kind of get a little taste of what it’s going to be like. You especially saw that during COVID when the Australia was looking, was trying to press United States and allies for COVID origins, and the PRC essentially hit the Australians with crazy sanctions.

And then the points that the PRC wanted the Australians to meet or to make like 11 out of the 14 had to do with their domestic politics. It didn’t even have anything to do with their external affairs. And so I see just how coercive the PRC is to the extent that they have leverage over other countries. And it’s not a pretty picture, but so to me, AUKUS is really important. But our partnerships with the Australians, with the Brits really, really important. Of course, Japanese and South Koreans as well. But talk to us about how we can be better collaborating with the Australians for defense posture?

Richard Berger:

Sure. I mean, the Chinese and the Russians are terrified by our alliances, not just on the military side, but across the spectrum of national power, obviously, personally on this as to avoid getting fired. But I do think we need to have really hard conversations with our allies, not just about spending, right? I mean, Europe is making leaps and bounds. We were with some Polish folks last night. I mean, what Poland has done is just incredible. They’re going to be the next superpower on the continent. But also about using American leadership and being humble about it, how our allies can specialize. Because if you look at the Australian budget, if you look at the British budget, I mean, most of our allies have budgets that are smaller than the US Marine Corps. And that’s a position that most US policy makers do not put themselves in.

And we don’t either understand that or press them on how they can specialize. So for instance, Australia is pushing forward with its GWEO, basically trying to build a lot more munitions. One of the things they’re going to be building is GMLRS great short to medium range surface to surface missile. Well, the US Army has yet to really embrace the idea of GMLRS with a maritime seeker to do anti-ship work. If our bureaucracy isn’t going to do it or isn’t going to do it quickly enough, then the Australians in many cases our allies, have bureaucracies that are more flexible than ours. They almost of necessity have to be. So there’s opportunities in munitions, there are opportunities in air power that really need to expand in Australia. And then really getting down to brass tacks, one of the biggest problems that we have, the most tiring conversation over the past two years, two and a half years since February, 2022, has been production diplomacy.

And if we look at how many victories we have or our allies have between them or with private industry, they’re fairly limited. One of the reasons for this is that the Department of Defense does not actually have the intellectual capital and the bodies to go out and do the work to figure out where these opportunities lie. Because each of these cases takes a while. It’s just as true of the diplomatic work we do on finding access agreements, but we don’t have a lot of good options to bring to senior leaders, whether it be in administration or in Congress about how to craft some of these deals, these interesting deals where our allies could actually help us, because we don’t have the people to go and talk to the technical people on the other side to figure them out.

So Australia is going to be a crucial ally for air power, for logistics, for INDOPACOM. And the key thing for the United States, really what we are getting for August, at least in the near term, is increased submarine presence in the Western Pacific. There are not going to be any more submarines in Guam. That’s just not a physically feasible thing. And the western coast of Australia is not only dispersed in terms of another operating location, but much closer than the West Coast of the United States, let alone the East Coast. So Australia has a lot more to contribute. I think we are just at the beginning of unlocking some of those opportunities. And the last example I’ll use is the accepted technologies list. I mean, we’re selling Australia attack subs, the most advanced weapon system ever built, but we’re still unwilling to do some much simpler things on munitions, which is disappointing.

Rebeccah L. Heinrichs:

So that’s a reform issue we got to get back to . . . the way I look at it is, there needs to be an audit. People think of since the Cold War, lots of people understand that our defense industrial base has atrophied since the Cold War. We focused on low intensity conflict in the Middle East. We weren’t thinking about how to deter and when if deterrence fails and major power war. And so that’s kind of where we are over the last 40 years. But other things happen too. We’ve increased regulations and our technology regime has made it so it doesn’t make sense anymore. We’re making it harder to share technologies with trusted allies. And our adversaries are stealing our technology.