Building a Sustainable and Successful Semiconductor Ecosystem under the Trump Administration

Senior Vice President, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company

Head of US Government Affairs, ASML

Director of Government Affairs, Tokyo Electron

Vice President of Government Relations, MediaTek

The next four years will be critical for American industrial policy as Washington seeks to strengthen its position in global semiconductor fabrication. Building on the Trump administration’s efforts to reshore semiconductor design and manufacturing, policymakers and industry professionals will need to collaborate on a comprehensive plan to foster a robust semiconductor ecosystem in the United States.

Senior Fellow Jason Hsu will moderate a discussion with Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) Senior Vice President Peter Cleveland, ASML Head of US Government Affairs Jonathan Hoganson, Tokyo Electron Director of Government Affairs Paul Treadgold, and MediaTek Vice President of Government Relations Patrick Wilson. They will examine potential policy changes, structural challenges, and opportunities for the United States to leverage its partnerships and build a more sustainable domestic semiconductor ecosystem.

Episode Transcript

This transcription is automatically generated and edited lightly for accuracy. Please excuse any errors.

Jason Hsu:

Good morning, everyone, and good afternoon or good evening to those watching online. Welcome to the launch of Semiconductor Tray and Geostrategy program at the Houston Institute. It’s an honor to gather today with such distinguished panelists and also my friends who have been working in this industry for a long time with staunch support also from the Houston Institute to help develop and shape the future of the semiconductor ecosystem in the US. Each of them understands we’re living through a profound change when it comes to technology as well as the global geopolitical dynamic shift. And obviously semiconductor has become sort of the centerpiece of the competition as well as the technology leadership positioning as well. So the program that we’re launching here at Houston is grounded in a simple but urgent premise, that in a era defined by strategic competition, the next frontier of the geopolitical influence will not only be shaped by military strength, but also by the leadership in critical and emerging technologies from semiconductor to AI to advanced manufacturing and secure communication infrastructure.

So we believe it is a important efforts to bring the industry leaders as well as the concerned citizens and the scholars and experts to think through a holistic approach to shape a healthy and sustainable development of the semiconductor industry. So our goal is to bridge the worlds of technology and strategy, connecting what happens in research labs and forums and what’s required on the actual labs and as well as the semiconductor policy discussion. So with that, I would like to introduce today’s panelists. Right next to me is our dear friend, Mr. Peter Cleveland, who is the senior vice president of TSMC. Please give him a round applause. And also importantly, without EUV machine, lithography machine, TSMC wouldn’t have made such advanced microchips. We have the Head of Government Affairs in North America from ASML. John, please say hi to everybody.

Jonathan Hoganson:

Hi.

Jason Hsu:

And also someone I have known dearly for a number of years now who’s been a very good friend to Taiwan, Patrick Wilson, Vice President of MediaTek. Please say hi to everybody. It’s important to have a fab-less company in this group as well because we are looking at the whole ecosystem. So we’re very much looking forward to his comments and his insights today. Lastly, but not least, we have Paul from Tokyo Electron, also a very important ecosystem player and equipment maker in the semiconductor industry. Please say hi to everybody, Paul.

All right, so today’s focus is how do we look forward in the next four years? Obviously the talk of the town two weeks ago was TSMC announcing its next phase of investment in the United States for a hundred billion dollars to build fabs, advanced chips, as well as R&D innovation facilities in the US. So I’d like to have each of them just shine a light to the recent development or industry insights and how they think about what the next years would be like for themselves, and then also provide some general overview how this administration can help support the industry’s development in a sustainable fashion. So, Peter, over to you.

Peter Cleveland:

Great, thank you, Jason. It’s terrific to be here at Hudson. This is such a distinguished place for thought leadership over decades and so productive. I see Riley Walters here, who I’ve worked with in the past, Patrick Cronin writes based out of Hudson, so many others, and it’s an invaluable contribution that your scholarship makes, hence the interests in appearing on a Friday. Jason has very colorful socks on this morning. That’s a strong man there. I’m just a little bit more passively attired today. So Jason talked about thinking ahead. Let me spin the clock back a little bit to give some history to friends here in the industry and to the scholars and others in the policy community. So at TSMC, we started thinking about coming to the United States in 2019 and that’s when we first started working closely with the Trump administration, Trump 1, and the team there, Wilbur Ross, Ian Steff. My good friend Patrick Wilson was part of the Commerce Department at the time.

And we were thinking about coming on shore, diversifying our footprint for STEM purposes, to get closer to customers, for other good reasons. And the relationship built on trust and collaboration started in 2019. We went around the country and looked at different places with Matthew Quigley from the Commerce Department on our delegation, and I think Patrick might’ve been receiving daily reports. We went to Syracuse, we went to Dallas, we went to the state of Washington, we went to Phoenix. We went everywhere to determine a good place to land. And Phoenix turned out to be that location for lots of good reasons. The governor there, Doug Ducey, had to welcome Matt out. The mayor there, Kate Gallego, fantastic. STEM talent, water, power, a good seismic layout. When you put together fabs, you want a certain type of geography. And so Phoenix fit TSMC extremely well. Fast-forward to 2020, the negotiations and discussions with President Trump and his White House continued in a very productive way.

And we announced in May of 2020 our first wafer fabrication facility, advanced, in the United States based on a dialogue with the President. It was a partnership. There was trust. He understood the importance of US economic and national security and that advanced fabrication had to occur here. Donald Trump understood that at the time and we made a very, very good deal with him. As Jason mentioned, and as we were talking about beforehand, there was a lot of spade work done in the years after. He was not president and Gina Raimondo and others really put the shoulder to the wheel to get legislation passed based on our initial investment. So we worked effectively with both administrations. Now let’s briefly talk about going forward. Three weeks ago we had an announcement with the president in the Roosevelt room. He could not have been more welcoming and supportive and collaborative.

He talked with us and publicly about the importance of US economic and national security once again. And that’s consistent with what Howard Lutnick had said during his nomination hearing in January, what Michael Kratsios has testified to during his nomination hearing to run the Office of Science and Technology Policy about restoring advanced fabrication here in the United States. And so the announcement was really a culmination of our partnership with Trump 1 and Trump 2 in terms of building eight fabs, six leading edge logic fabs, two advanced packaging fabs, and importantly, including a major R&D center that we would co-locate.

When you fabricate, you want R&D to physically be nearby to pick up learnings and amplify the success that we are going to have in Phoenix. And so R&D will be a critical component, a major R&D center there. So that’s where things stand now. We are operational with our first fab. Off take is complete. It is running at a very, very high yield. We are well underway with construction on our second fab. Third fab, groundbreaking should occur very, very soon, but the United States is an ideal location for TSMC to expand its footprint. Home remains Taiwan. I see Johnson here from the Taiwanese government. He’s been a fantastic partner with us as we have moved in this direction, not just in the United States, but Japan and Germany as well. So I’ll look forward to joining in the conversation with Jason, but we are optimistic about our collaboration and partnership going forward with the Trump administration as well as Capitol Hill.

Jason Hsu:

Over to you, John. Obviously without ASML providing the most advanced lithography machine, advanced chips wouldn’t have been possible. You’re such an important, instrumental ecosystem player in this. What do you see as the next four years moving forward for you and the company and also US’s development of semiconductor industries?

Jonathan Hoganson:

Yeah, I see opportunity, but let me just back up and thank you for hosting us today. I was thinking about it this morning and I don’t want to date us, but between this group, there’s probably 60 plus years of semiconductor experience on this panel right now. So we’ve all kind of seen it at different roles and so it’s a great opportunity to exchange and share views overall. So again, thank you for that. As I said, we’ve got a lot of experience in the semiconductor industry and when I first started in 2012, we’d get a lot of questions on Capitol Hill about why we should even care about semiconductors. I had one lawmaker say to me, “Semiconductors, we make all those in Asia. Why should I care about that?” And another famous story is another lawmaker said, “Semiconductors, why don’t you make full conductors?” So we’ve come a long way on that to a place where you see the CHIPS Act and you see investment and you understand that lawmakers really do value the importance of semiconductors and having those manufactured here overall.

And ASML is very supportive of that initiative as well. I think as the knowledge base has grown around semiconductors, there’s been a lot of discussion, a lot of plans, but in many ways it can be an adversarial approach, which is unfortunate because I think there’s a way for industry to work closely with government going forward. And so as I think about the next four years, I really see an opportunity for close collaboration because we ultimately have the same goals. ASML has 8,500 employees here in the United States. We manufacture in Connecticut, we manufacture in California. We have a big presence, actually three sites in Arizona supporting our customers, but also a training center there as well. So we are heavily invested and plan to continue to invest in this. As the semiconductor industry grows, we plan to support that and be a critical role across the board.

I think as we think about the future, I think the CHIPS Act was a great step forward. As Peter acknowledged, it was started under the first Trump administration and carried forward in the last administration. But I think that that was a piece. What was a little bit lacking was a comprehensive plan. So what is it that we want to do in the United States? How much do we want to make? What is our strategy to build out that plan overall? And I think there’s an opportunity for industry to collaborate closely with this administration, with Congress to help develop and fulfill that plan going forward. So it’s questions about, “How much advanced manufacturing do we want here, advanced nodes? How much sort of what we call legacy nodes or mature nodes manufactured here?” That’s critically important as well.

“How much packaging do you have and how do you get there? What’s the R&D component to that?” These are all pieces that need to be discussed and fleshed out. “What’s the proper role of incentives?” I think there’s some questions about that right now, but what is the proper role? And we would argue that the incentives are critically important to all those things. So that’s one piece. The other thing that the last Trump administration was really strong on and I think has been lost in the past few years is intellectual property protection. I think as you think about maintaining the lead, maintaining your intellectual property and that know-how becomes critically important, making sure that you have that. I recall in the last Trump administration, they’d really made that a focus. They had a China working group they’d stood up to focus on IP protection overall. And so I would like to see some focus on that going forward because I think across the board, our intellectual property really is the lifeblood of what we do.

At ASML, as you mentioned EUV, what we do is sort of like Harry Potter wizardry stuff. I don’t fully understand it. I’d to take credit for it, but I don’t understand it at all. I do understand a little bit, but anyway. . . But it is incredibly important to technology. It’s important that we preserve that going forward. It’s important that we preserve TSMC’s intellectual property, MediaTek’s intellectual property going forward. So as I think about the next four years in terms of things where we can work together, I’d focus on those two pieces.

Jason Hsu:

Great. Over to you, Patrick.

Patrick Wilson:

It’s really great to be with you. I think as John just said, it’s really important for folks who are tucking into the semiconductor industry to understand something that you just said, which is this is crazy science fiction. The semiconductor industry are machines making machines more advanced than they are. Unpack that for a second. Literally, the machines are making machines more. . . Infinity. That’s the last 60 years, machines making machines more advanced than they are. I think that is so often misunderstood and lost in the process. And the part that MediaTek, what we play in that which are the designs, to get them ready to go into a manufacturing process that we hope at the end with incredible leadership from partners like TSMC that look at what we designed, they fact check it, they double check it, they help make sure that it will really function as the designers intended.

But let’s not make any mistake about the absolutely amazing process of making semiconductor devices that power everything. When you came into work today, whether it was your coffee machine, your Peloton, your phone in your pocket, not only am I proud to say that MediaTek made about 2 billion of those devices and they’re all across in every home, whether you spoke to your Alexa on the way in or perhaps your car’s navigation system. These devices are embedded in everything we do and it’s going to increase. The excitement about that is, and I think as a lifelong Republican, which is why I was excited to be on this panel and say I’ve been a combatant in the politics of how to do technology policy in the administration, in the Capitol Hill, in both the House and the Senate. And I think that we’ve had a little bit of a history lesson, and I’m so glad Peter started there.

I was kind of thrown back a bit to Chris Miller’s excellent book, which everyone talks about, Chip War, which if I were his editors, I’d be like, “That’s a great title.” But the actual book, I don’t want to spoil it, is actually the history of the semiconductor industry and an important takeaway as we think about trying to engage with this new administration about the CHIPS Act, something I take great pride that we created at the Commerce Department. But I think it’s important to remember that this incredible innovation machine that is the semiconductor industry, it really has grown and flourished separate from government. And that’s really a hard thing to think about because a lot of us here in DC, we’re very DC-centric. We think about the financial services or telecom or banking, heavily regulated industries, electricity from the very beginning. Our industry is not like that.

And I’m going to illustrate it in just one quick way. When I got home from Iraq in 2005, I’d been a Hill staffer, I was deployed, came back, I didn’t know what I wanted to do, but I didn’t want to work on Capitol Hill anymore. My former intern, Ian Steff, worked for one of his clients at a law firm. It was called the Semiconductor Industry Association. I remembered them vaguely. I was like, “I think they came in to see me when I was running the Manufacturing Caucus. Yeah, sure, I’ll go talk to them.” When I was hired in 2005, I was the very first lobbyist ever for the semiconductor industry. At that time, $150 billion industry. Think about that. They didn’t have a lobbyist. They weren’t in DC. It took a whole other six years after I was on the job before we eventually moved our headquarters from San Jose.

Intel, the most important company in the world, their head of office was in California and came to DC, completely crazy things for people to think about that only that many years ago, in the span of one career, we have gone from not really engaged to today, you can fill a room in DC talking about chips, which back when I was lobbyist, I would’ve been so excited about. My joke was always to the Hill when they were asking about semiconductors, I was like, “Yeah, they’re the part-time conductors. They just do really short symphonies.” That was the idea. But it’s important to think about how we have engaged on this topic and how we tell that story. And I think many of us. . . I was in the Trump administration when Secretary Ross turned to Ian and I and said, “Hey, you guys worked at the SIA for many years. You’re our semiconductor experts. How do we get TSMC to come to the US?”

And I had to tell my boss straight up, “I don’t think they will.” And he was like, “What do you mean?” And I said, “We don’t make enough engineers. We have terrible tax policy. We have really high regulatory costs and we have massive litigation, all things that they want to avoid.” The reason leading edge manufacturing has fled the US is because we messed up the ecosystem. And those things take a lot of time to right the ship, to get it right. And I think because Secretary Ross was not a politician, he said, “Well, we’re going to get to work on that. We’re going to try to fix those things.” And if you look at what the Trump did is we worked on the tax policy to get that right. We tried to reduce regulations and we passed the CHIPS Act to create cash incentives for companies to choose to operate from here versus anywhere else.

And ultimately, that’s what we’re really talking about is from where. . .? We are all global companies. From where will we serve our customers? And for the US government, for the Trump administration, the question is, “How do we get the recipe right for the ecosystem to choose to have people serve their customers from here?” That’s how we tell the story. I’ll wrap up with the binary choice I give. Every time I sit in front of a member of congress, a senator or a staffer, I always lay it out. I say, “Anybody who comes in to talk to you, to ask for something, whatever it is, whatever policy prescription they want you to implement, you ask them, ‘Whatever you want, does it make it more or less likely innovation will happen here?’” You should ask them every single time, whatever the policy prescription is. That’s what our dream would be, is we want the ecosystem to always win, do innovation here, invest here, expand here, create cutting edge technology here.

That’s what we want to happen. And I think policymakers are under a lot of stress to pull and push in different ways. But what we hope to do, as a group and through this really awesome project at Hudson, is to remind policymakers that you’re always facing that question, here versus there? And if you give an advantage to our international competitors, they’re going to take it. This is a fight. This is a competition. So we need to make sure that America is the best place to invest, we have the best engineering talent, we have the best research and development, we have the best tax policy, we have the best regulatory environment. That’s how you win. And there’s just no shortcut for that.

Jason Hsu:

Thanks, Patrick. And that’s a perfect segue to Paul, who’s here on behalf of the Tokyo Electron. And one of the important characteristics of this industry is its global footprint and innovation integration. And Tokyo Electron being an important player in the ecosystem, also with TSMC’s recent success, projects in Kumamoto, in Kyushu province in Japan, tell us a little bit about how Tokyo Electron plays in the ecosystem. And also maybe you can shed some lights into TSMC’s very much lauded successful projects in Japan, and then how you work with the government and the industry. And I think that would be a great takeaway also for this audience and also the current administration who are looking to build a more robust ecosystem here in United States. So over to you, Paul.

Paul Treadgold:

Well, thank you so much, Jason, and thanks to my fellow panelists and the Hudson for hosting this great event. It’s a really honor and pleasure to be here. I mean, those are all great questions, Jason, and would love to and will address all of them. Just to maybe take a little bit of a step back and give some background about Tokyo Electron, because I understand that unless you’re really in the weeds of the semiconductor industry, you may not know who we are, what we do. So, we’re a semiconductor equipment manufacturing company, we’ve been around for more than 62 years, headquarters, obviously, as you might guess by the name, in Tokyo, but have been in the US for more than 30 years, US headquarters in Austin, Texas, and have about 3,500 employees across the country, 20 sites, 11 states. That’s all to say that we have grown significantly in the US over the past several, several years and plan to continue that growth. We have a manufacturing site in Minnesota just outside of Minneapolis, in a city called Chaska, that we’re very excited about, and we’re actually investing in that facility and growing that facility to become what we’re calling our fourth factory. So, we have three ginormous factories in Japan, and then the one in Minnesota is coming up to the same par and same level as that factory, which is a really vote of confidence from our leadership in Japan about the importance of doing manufacturing and having a strong footprint here in the US.

We also are one of the two leading founding partners of the NanoTech Complex in Albany, New York. About 20 years ago, our CEO at the time had a vision to partner with IBM to set up really the largest integrated R&D center in the world, in Albany, and now it’s one of the leading destinations for R&D in the semiconductor space around the world. I think when we talk about what the future prospects for the semiconductor industry are, I’m extremely optimistic, not only globally, but especially around what’s happening in the US. I think what I’m especially gratified to see with this particular panel is you have companies that are all choosing to do business here in the United States, we’re all non-US headquartered companies, but have been here for many years, and are doubling down on our commitment to doing business here in the United States.

Why is that? It’s exactly what Patrick was just talking about, the visionary mission behind the CHIPS Act, which was hatched under the first Trump administration, as Patrick was just talking about, we were talking a little bit earlier in the green room, right prior to coming out here, usually when you talk about programs and policies that have some sort of tax incentives or funding for businesses, it’s like a crisis, you have to bail a company out, and it’s something that’s an immediate thing that you need to take care of, the CHIPS Act is actually really visionary, it’s trying to set the US up for success. And so, I really commend Patrick and his colleagues under the first Trump administration for having that vision and understanding this semiconductor industry was a little bit of a sleeping giant, we didn’t have a strong presence as an industry in Washington D.C., we weren’t pounding the pavement going up on Capitol Hill and bombarding members of Congress and staffers, talking about the importance of our industry. It was actually more that the government looked at the industry and was like, wait a minute, what’s going on over there?

That’s actually really exciting, that’s really important, and the development of the industry is really important for the growth of jobs in the United States, good paying high wage jobs, good skills, recruiting people who don’t necessarily need college degrees for roles as field service technicians and engineers, but also US economic security, US national security, and as those things are made successful here in the United States, that will go down onto the benefit of strong US partners and allies. And so, the point that I would make around having this panel that you’re witnessing here today is how the US has become a place of a choice, and a really strong destination for foreign direct investment for companies like ourselves. And so, I’m really optimistic that working with the administration, work with Congress, to build upon the foundation that has already been laid, to continue to focus on things like investment, tax credits, and deregulation, as Patrick talked about, but also workforce training, and also funding, federal R&D initiatives, and pre-competitive research.

Those are all things that are going to set the US up for success. And Jason, you mentioned TSMC’s development in Kumamoto, and obviously I would allow Peter to speak more intelligently about that than I. But what I would say to that is we’ve seen examples both in Taiwan and Japan and elsewhere around the world of governments that are really working hand-in-glove with industry to create unbelievable developments that have huge impacts on the local economy, and on the country’s GDP. And one of my favorite stats from the Semiconductor Industry Association is that for every dollar of funding that the federal government spends in R&D results in a $16.50 in US GDP growth. And other countries, including the US, obviously, have recognized that too, and the semiconductor industry stands ready to certainly be a strong partner in realizing that growth. And Tokyo Electron is an equipment supplier, and a toolmaker, and a seller to companies like TSMC and all the major chip makers out there, we stand ready to support our customers in those efforts. So, maybe I’ll stop there and then would love to dive into the questions that I know you have prepared.

Jason Hsu:

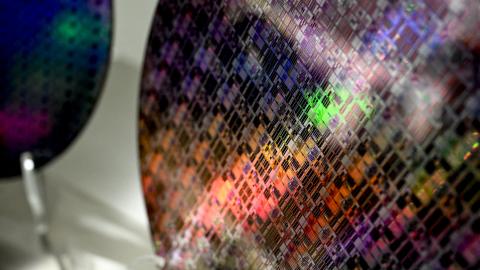

Yeah, thank you Paul. And let’s dive right into the ecosystem gaps, and strength, and that we are so much focused on here today. And I’ll give you a little bit of a historical background of Taiwan’s semiconductor ecosystem success, and also why it is becoming a global powerhouse as it is today. And obviously, it’s not a overnight success, building a fab, it’s not like opening a bubble tea shop, it’s not something like you do overnight and it happens. It takes Taiwan 30 years to build up that ecosystem. Started with a single idea to manufacture semiconductor chips, and then that whole thing spun out to a science park, where the ecosystem, the delivery of the entire ecosystem built within really the radius of 10 miles. And everything that’s needed to build and make that chip, it can be done practically within that ecosystem.

And so, that miracle, if you will, has been a good example for countries that are now thinking about building their own chips plants or ecosystem to follow. So, today’s panel is really an example of how that ecosystem is constructed. We have foundry, which is basically the manufacturing piece of the actual chip, we have equipment maker, without them the chip wouldn’t have been possible, and then we have design, what we call a fabulous company that make the design of the chip that then being a commission to company like TSMC to produce, and then we have other equipment makers as well. So, I want each of you just to talk a little bit about from your company’s perspective, what are the biggest structural gaps that the current US semiconductor ecosystem needs to meet in order to quickly replicate, if not a entirety of the semiconductors model, or at least to make something work here in the US more efficiently and more effectively. Over to you, Peter.

Peter Cleveland:

Well, that’s very well said, Jason. It is useful to have the ecosystem up here on the stage. The DNA for TSMC comes from ASML and Tokyo Electron, couldn’t do it without them. And then, we bow at the feet of MediaTek. They’re the customer, and we’ll do anything for the customer. We have 500 customers, and as Patrick very thoughtfully described, do we on an iterative basis, go back with them, go back and forth with them, they’ll send us their design aspirations in a GDS2 file, and then we’ll make their brilliant silicon. And so, we all have a different perspective. We’re the chip maker, and so structurally there are issues here in the United States. President Trump is focused like a laser beam on ensuring US AI leadership. He’s very blunt spoken about it with us, and TSMC likes that. We’re very direct, we’re no-nonsense, the reason we’re here is to build advanced chips.

There are different types of chips, there are accelerators, there are graphics processing units, there are central processing units, we’re going to build those in Phoenix to sustain US AI leadership. It’s not easy. The United States is a different marketplace, labor costs are high, and through the CHIPS Act, there are mandates that Donald Trump may address and fix. He won, he wants to change some aspects to the law, and we’ve given him some ideas to do so. Don’t micromanagement our workforce approach, he has some views about DEI requirements, environmental permitting is something that could be expedited, and so in concert with him, we’ll take those steps. He wants to help TSMC run faster, build faster, be stronger on the ground here, and so that’s why the partnership is excellent in the first few months of his administration. So, when you talk about structural issues, we are in a good dialogue with the Commerce Department, Michael Grimes, the person that runs, who’s the investment accelerator there, the people that run the CPO, the CHIPS Program Office, and we’ll continue working with them very closely regarding the project in Phoenix.

Jason Hsu:

Yeah. Maybe just dig a little bit deeper into that. And I know there’s been a big announcement, TSMC investing $100,000. What are the issues that you hope this administration can help improve them or expedite? Is it a workforce issue? Is it a incentive issues? What are you hoping to see? I think you’ve said so well that this administration is laser focused on making semiconductor stronger and build faster. So, what are some of the, one or two or three things that you think-

Peter Cleveland:

I’ll give you an example of that. So, I mentioned before, we are well underway in terms of construction with our second wafer fab, we have not started to break ground on our third wafer fab in Phoenix. We would like to start next week. We need an air permit from Maricopa County, that is blessed by EPA, so that we can proceed with construction, full excavation beyond just grading the site, we’re ready to go. And so, environmental permitting needs to be expedited, and Michael Grimes, who is the top aide to Secretary Lutnick, is extremely accomplished, and is right on top of the problem. And so, that may sound a little discreet, but it’s not.

We’re on time, we’re on schedule, we want to proceed with P3, our third fab, and additionally, we need the air permit to build something called an IRWP, an irrigation reclamation water processing facility to recycle water. We can’t start with that either until we have the federal and state authorities and local authorities give us the permitting we need. So, this administration is focused on helping us receive the permitting so that we can construct the third wafer fab. That’s one example, getting into the weeds a bit, of the collaboration that’s ongoing day to day.

Jason Hsu:

Yeah. Thank you, Peter. John, some questions, structural gap and what you’re hoping to see.

Jonathan Hoganson:

Yeah, I think that, I want to touch on the ecosystem concept, right? I think there was a decision made, it’s critically important to rebuild the semiconductor ecosystem, because when you talk about costs with semiconductors, Peter talked about how expensive it is to do that here, part of that is the breakdown of the ecosystem and those structural pieces. So, it’s all the parts that go into manufacturing, and it’s actually not just one ecosystem, it’s a series of ecosystems. So, if you think about our EUV machine, for example, that machine is ultimately assembled in the Netherlands, in Veldhoven, but it takes thousands of suppliers, we’re working with companies like this ZEISS corporation to make the lens, and we are using highly sophisticated laser technology, we’re taking a droplet of tin that moves at 50,000 droplets a second, we’re shooting it three times with the laser and making a light that’s the same temperature of the sun, we’re harnessing that in a vacuum, bouncing it off some mirrors, and then puts an image on to that overall wafer at Peter’s factories, to do that overall.

And that’s one machine, that machine is transported on 747s over there, so it is a massive investment for one part, one piece of the manufacturing process overall, that goes into that. Tau is doing their parts as well, they’re adding those machines. So, there’s a massive ecosystem that goes into making a semiconductor fab, it’s not just a turnkey operation, it’s not making ketchup, or nylon, or something like that, it’s many, many pieces that go into that. So, I think the challenge there, and I mentioned it earlier, is that gap in understanding the ecosystem, and building out that whole ecosystem. So, looking at the permitting, making sure that we have all those inputs that go into this, it’s, again, it’s the chemicals, it’s the packaging, it’s the tools that go into it, it’s the talent, all of those things have to go into this ecosystem.

And so, we’ve started with the first step, with getting fabs going, we’ve got to invest in the R&D, but then we have to continue this, and I would say having that staying power, that duration becomes critically important, and then the partnership at the end of the day too. I think, where we started this question is, what do we see going forward? I do see opportunity, I see a lot of opportunity for our industry, all of us and others that I see in the audience that are also in the industry partnering with this administration and the US as a whole, to make sure that we’re rebuilding that ecosystem that ultimately will bring those costs down and make the US a leader again in semiconductor manufacturing.

Jason Hsu:

Patrick, you actually represent customer perspective on this panel, you’re the one who is basically giving orders to companies like TSMC, and then TSMC use John’s machine to make the chips that you will sell to your end customers. You seem to be an important player but weren’t included in the last four years, what’s your anticipation going forward, and how do you. . . I think it’s good that you’re here, so please share with us your perspective on this.

Patrick Wilson:

Thanks Jason. And selfishly, the customer is the most important part of the process because it drives all the other capital decisions. TSMC can’t make this incredible leap to take $100 billion and make a bet, right? If I gave you $100 billion, and you looked at the risk board of the world and said, where are you going to put your bets? And it goes to another gap in understanding, is people who are laypeople, who are like peering into our industry for the first time, they forget that these are really long-term investments. If you’re going to write a check for $100 dollars, your life cycle is 30 to 40 years, right? Long past politicians, and elections, and governors, you hope you get it right at the moment, whenever you make it, but the out game, you don’t know, right? And it requires a lot of people, and I think one of the biggest frustrations I’ve had is trying to explain to people that I was so wrong. . . This doesn’t happen in D.C. very often.

But I was really wrong because my boss, Secretary of Commerce, asked me, “Hey, Patrick, you ran the Semiconductor Industry Association, why can’t we get any leading-edge capacity?” Because there was zero. In 2019 when we sat down in the secretary’s office, it was zero, and had been that way. And all these really smart people from CSIS, and from Peterson, and other people sat down with us, and they were like, yeah, in the history of the world, nobody has ever lost leading-edge manufacturing and got it back. Whether it was the textile industry, the auto industry, if it’s gone, it’s going to migrate, and it’s going to stay there because it’s just inertia, right? It’s just going to be on the way. And so, the odds weren’t great. So, when my secretary asked me what do we got to do to make this happen? I said, it’s not going to happen. I’m sorry, I really want it, I spent my whole life articulating the reasons why we want leading-edge capacity in the US, but it’s not going to happen because it takes so much patience.

It’s outside of investor tolerance, spending $100 billion, where you don’t get a return for five or seven years, investors don’t like that, politicians don’t like that. We don’t have any programs, there were no federal programs in 2019, there wasn’t a single federal incentive program. Every other country around the world had them, and the US has no industrial policy, and it had never happened before. So, there was a lot against us, and frankly, I have to tell you, in my 30 years in politics, I have never had a single thing as successful as the idea. . . I actually get quite emotional when I think about it, when Ian and I in the cafeteria at the commerce department, two former SIA employees saying, if we get this right, there could actually be leading-edge capacity in the US in four or five years.

And to think that we’re sitting here now, and wafers are going out the door in Phoenix, at the leading-edge nodes. . . It’s a miracle. It is a policymakers’ miracle, right? You never get those touchdown dances, and that’s why it’s sad to me I think that the president never got his credit, for his administration having what I consider to be the most important industrial miracle in the last 100 years, to make that happen from policy instigation to success. And for us, as a customer, we look at that and we think, we just got to have more choices, right? We want resilient supply chain. If the COVID situation didn’t teach us anything, we had to have that resilience. That’s why we’re delighted, we’re going to continue to partner and be a Taiwanese company, and use our partners in Taiwan because it’s a safe leading-edge place to be, but we’re going to have other choices too.

And Jason, we didn’t mention it yet, but we took some heat back in 2022, when Intel was trying to stand up their foundry business, and our CEO came to D.C. and said, Hey, we’re going to work with Intel too because everybody wants multiple suppliers. And so, when Intel and when they’re going to bring their 18A to market, we’re going to take a look at that just like everyone else, because competition is the American way, and having the smartest people in the world fight it out to make really amazing technology for the AI universe that’s ahead, and other challenges that we don’t even know about yet, like what quantum is going to require, and things like that, we want that foot race, not just with China, not just with other players, but among the allied trusted technology providers.

I would be fined if I didn’t say for us the biggest gap is talent. Just some facts, so we have about 1000 employees in the US, and 75percent of those employees have at least a EE, an electrical engineering degree, that’s a five-year master’s degree, it’s the terminal degree in electrical engineering, 25percent of every one of our hires in the US has a PhD, right? So, here’s the bad news. You talk about what we don’t have right, if I could fix, if I could sit down with Congress and fix it, we are making today the exact same number of electrical engineers today that we made in 2000. In 2000. Our industry was a $60 billion industry in 2000, we are on par this year to be a $650 billion industry, all dominated by American companies, and we’re still making the same number of electrical engineers, that’s embarrassment for our country, we have to fix that.

And we either have to steal all the smartest people in the world, as we’ve continued to do from around the world to come here, we need to do that too, but we need to make more engineers, and policymakers need to prioritize that. Because for design, for every part of our industry, the one thing we all have in common is we need brilliant engineers to make the magic happen, the science fiction, that is what ASML does here, and what Tokyo Electron does here, it is the seed corn of American innovation.

And the bad thing, Jason, it’s just such a long game. If you’re going to make PhDs right now, none of these politicians who make the decision to create the pipeline, none of them will be in office by the time those men and women receive their PhD. There’s a young girl right now learning math and science in first grade, I’m going to be well retired by the time she receives her PhD in material science or electrical engineering. And you have to have vision, politicians have to have vision to see that that’s the arc for America’s technology future is to get more engineering talent.

Jason Hsu:

Paul?

Paul Treadgold:

Yeah, that’s a really perfect segue, Patrick. I’d love to pick off of that. And I would say, to answer your question, Jason, what I think we would view, or I would view, as one of the rate-limiting factors that could potentially get in the way of the success of the industry here in the United States is exactly what Patrick is talking about in workforce. Tokyo Electron’s business model is significantly different from MediaTek’s obviously, where Patrick was just saying that 75percent of your workers have electrical engineering, or EE degrees, actually more than two-thirds of our workers in the US hold positions for which you don’t even need a college degree. And the reason for that is because we have our equipment at our customer sites, like TSMC, and we need people on the ground, our field service technicians and engineers to make sure that the equipment is up and running, getting the software updates, and working as it should, because if a piece of equipment goes down, TSMC is going to be really mad at us, and that’s going to impact the entire ecosystem, so we need that equipment up and running. What do we do? We have, as an industry and worked with our peers as well in the equipment space to do a lot of outreach to community colleges, vocational schools, high schools, to become a field service engineer. You can come out of a vocational program, a community college, even high school, go through a five to 12 week training program, get trained on the basics for what it means to be a field service engineer, then go into a slightly more intense training program within a specific company, whether that’s ASML, Tokyo Electron and really within a matter of months you have the basic fundamental knowledge to be, on the track to become to have a career in the semiconductor industry for years and years to come. They’re high paying jobs, they have great benefits and great career trajectory and growth as well and it’s just really cool to be part of an industry where you’re, as Patrick and the other panelists were saying, you’re kind of changing the world and creating the most innovative technology possible.

One other thing that I would mention in this space, actually two other things. One is one of the things that I’m kind of most proud of is working for Tokyo Electron to really be involved in, is the work that not only our company, but the entire industry is doing to focus on hiring veterans and those transitioning out of the military. We find that veterans naturally have an inclination to potentially want to continue their work in kind of national service serving their country in some way and so the natural overlay that the semiconductor industry has with US National Security allows them to continue that mission. Of course, the other part is that as you pick up skills in the armed services and technical skills and know-how, you might be working on a tank or diffusing bombs, but believe it or not, those skills are actually directly applicable to positions throughout the semiconductor industry supply chain and the ecosystem here in the United States.

That’s something that I know we will continue to work on and so I think as an industry, we’re trying to think creatively, how can we get people excited to work in this space? How can we lower the barriers to entry for people to come into the industry? How can we tap into untapped populations who may not think that their skills are applicable or may not have considered working in this industry before? How can we make sure that they’re aware that we have an open door and would love to invite them in for a role, whether it’s pursuing an advanced degree and that’s extremely important, as you heard from Patrick, for the success of the ecosystem or if it’s coming in as a field service engineer. Those roles are all equally important and vital for the success.

One other thing that I would mention and it has to do with a partnership that I think exemplifies the strong relationship between the US and Japan, is a program called the Upwards Program. It’s a partnership of six universities in the United States, five universities in Japan. It’s co-sponsored By TEL as well as Micron, which is another US-based semiconductor manufacturer and really it’s an opportunity to put 5,000 students through that program, allow them to pick up fundamentals in the university setting for semiconductors and set them up for success and of course to create cross-cultural collaborations between the US and Japan. Those are some of the innovative solutions we’re trying to come at as an industry to generate the talent and long-term term success here in the US.

Peter Cleveland:

Just to on that real quick, just to add. These are all great points. One thing I think the industry has to do a better job though too of is telling this story about what we can do because it is electrical engineers, it is people with PhDs in physics, but it is also people that are machinists that are building these things at the end of the day. Again, not to keep bragging about what we do, but we all think what we do is the most important part of the semiconductor manufacturing process and I think we can agree we all are the most important, but we have a wafer handler that moves wafer back and forth, it moves back and forth at 35Gs, right? We have physicists that are figuring out how to make that work, but then we have skilled people in Wilton Connecticut that are grinding the lenses, that are grinding that thing down, basically by hand and they are skilled craftsmen and craftspeople that are making these parts.

You have these physicists that are, again, putting together crazy physics all the way down to people that are really truly skilled craftspeople and are critical overall. I think it’s something the industry has to do a better job, in addition to the college parts, but just explaining what the opportunities are that are out there. I tell lots of kids in high school and other places that there are so many opportunities in the semiconductor industry going forward.

Jason Hsu:

Yeah, absolutely very solid points. Also, related to this, what Taiwan has been doing is something that we call Semiconductor Institute, National Semiconductor Institute that was created among four universities that have been a long-time cultivator of semiconductor talent. That might be something that US could work with Taiwan to develop more talent pipeline and as well as exchange because time and time again, I keep hearing the talent deficit, the talent shortage has been a very important issue that US needs to solve. Also, I think both John and Paul have a very important points because if you look at the way these semiconductor ecosystem and as well as its manufacturing, it’s not just the top engineers with PhD degrees or master’s degrees in EE, it is those technicians or skilled workers or those very experienced line workers, that treat this fine process like craftsmanship and it’s almost like building something to tolerate zero mistake. It is to that level of perfection that would require years and years of dedication. If there’s something to be learned from Taiwan or even Japan for that spirit, it is dedication and also years and years of efforts to fine tune something that is so perfect and also zero mistake for that sake. That’s a very solid point. Thank you, John.

Patrick Wilson:

I think your point just about collaboration is really one not to miss. If you’re taking notes at home about what the recipe that our crew is commending to the Trump administration, I would say collaboration is America’s superpower, right? We are really good at it. It’s an American trait. We attract foreign companies to come here and invest. We partner really, really well and I think the example of E-Tree, Taiwan’s National Research Enterprise is a really good example, but the US also did that. Back in the day when we had an existential crisis in the 1980s during the Reagan administration, we created Sematech because we said we’re going to be out of the game, so we’re going to charter a federal research enterprise to create Sematech, to create the machine tools that we’re living in that era still, that defined the move to 300 nanometers, the size of wafers we’re at today. That was government leadership on research and then collaboration across the whole ecosystem. That’s the example and I just think we’ve got away from that a bit. There’s a lot of focus on and I’m very proud of all the components, the tax components, that are incentives, the cash incentives that are part of CHIPS Act, but the research part is so important and not to lose that thread, that if you don’t invest in the research collaboration, you’re not going to get the leadership over decades.

That’s what Taiwan’s experience really is commending to the world, is get your universities and your companies and NGOs, get them all working in the same direction, to collaborate and then you’re going to solve problems faster. I would just say, luckily, that’s a very American thing and I’ve been really pleased since being at MediaTek. You look at the universities that we are partnering with, they’re all the most important engineering schools in America, MediaTek, either has a live-in professor, we underwrite research. It’s just how everybody in the semiconductor industry works. You look at each one of our companies, I would bet and I say this, but I’ve actually measured it, every single semiconductor facility is like a 10 minute drive from an R1 research university. That’s not an accident. I’m an artillery officer, so I was looking at target analysis, dots on a map. All of semiconductor companies. If you look at why Silicon Valley is there, amazing universities in the ecosystem and that is really what drives our industry and so sometimes that gets lost in the shuffle, is that collaboration globally with global partners, but particularly universities and the private sector to solve. Literally guys, we’re talking about the hardest problems known to humans. I mean, we’re literally in Star Trek land. Beyond the next, we’re manipulating atoms to make new devices and we just have to keep in mind that it’s all driven by that collaboration.

Jason Hsu:

Yeah. Thanks Patrick. Let’s talk about regulatory regime and it’s implications. I know this is deep water area, everybody’s concerned. Towards the Trump 1.0, the so-called entity list was created and I know TSMC kind of came to bear the brunt of the entity list because some of its customers is on the entity list and continue on to the Biden administration. The so-called small yard, high fences was kind of the main tone of the administration strategy to slow down China’s competition in the semiconductor and also continuously to implement the export control and other measures against the China’s race in this period. I wanted each of you to kind of just talk a little bit about some of the, I guess what we’ve been seeing might be and I’m trying to come up with a better word, but I think the word I’ll use is unintended consequences of the policy that would probably impact the industry. How do you view the role of export controls and its other regulatory regime in securing US leadership without undermining the global collaborations? What do you hope this administration could do differently than previous administration to make this a more coherent and comprehensive support for this? Peter?

Peter Cleveland:

Sure. President Trump has picked a few individuals to assist him in this space and we’ve met with those individuals. David Feith, the most senior assistant to the president at the White House, is very well known to TSMC. He’s outstanding in every way. Has deep experience. Landon Heid as well, who will be the chief regulator at VIS, is a superstar in the making and we’ve had a good dialogue with them already about the complexity of export controls. 75percent of our business is in the United States, 10percent is in China, so the focal point is that business in China and the types of chips we sell, our goal is to sell to the commercial marketplace in China and we need Landon’s help and David’s help in terms of coordinating to make sure that our silicon gets sold and distributed in the right ways, consistent with US law. We adhere to the letter and the spirit of all US export laws and regulations. Personnel is policy and they’ve picked two excellent people and then an Eminence Greece type in Jeffrey Kessler to oversee as undersecretary the whole operation. We feel like they put their best foot forward and we’re in active communication with them and coordination vis-a-vis our global sales, particularly focused on China where they have serious concern.

Jason Hsu:

John?

Jonathan Hoganson:

Yeah, I mean ASML abides and follows all export control rules, regulations, et cetera, like I think all the companies do here, so I’m not sure I’m going to say anything new on that front. I agree with the comments about David and Landon and Jeff. I think it’s a great team going forward, looking forward to working with them as we get this all fleshed out. I think the biggest challenge is just around clarity and direction, making sure the rules are clear and that we have an opportunity to have feedback. I think there’s been a challenge and some of the rules that have come out as interim final. Typically the process would be a feedback loop, back and forth with the administration to talk through what makes sense, what doesn’t make sense, what you can actually do in practice and you can’t. I think we’re saying this play out a little bit in the AI diffusion rule that came out and there’s a lot of questions as to how that’s going to go forward. I think the more dialogue there can be with industry going forward is a positive place for us to go forward, but export controls are a critical tool of national security and I think all the companies here agree and understand that and we’ll move forward with them. It’s just a matter of making sure that they’re clearly defined going forward.

Jason Hsu:

John, I want to kind of press you on this. What’s that? The equipment maker also comes under export control during the Biden administration and I know we’ve talked about this. Are there anything that you would advise or I guess in your opinion to think through company’s strategy, especially knowing that this will be a persisting trend going forward, to prepare for a more, I don’t know, again struggling to find a word, bifurcated kind of market approach, US and its allies versus China, for that matter.

Jonathan Hoganson:

Yeah, I think both administrations have both said that, neither of them said you can’t sell in China. They’re not talking about decoupling, at least I haven’t seen that out of this administration, if that’s what kind of where you’re going overall. I think the question is making sure those rules are clearly defined as to what you can and can’t do. Then I would also go back to what I started with too on the IP protection side of things. I think that we have to make sure that in addition to securing what is critical national security technology, that we’re also making sure that proprietary technology is kept and then there’s the run faster piece of this as well, right? Making sure that we’re investing for the future. It can’t just all be about putting walls up. It’s got to be about expanding the markets going forward. Patrick talked about the fact that it’s $600 billion industry. It’s going to a trillion dollars. This industry is going to continue to grow going forward. There’s enough business for the whole world out there. We need to figure out making sure the rules are clearly defined and making sure that we are investing for that future to get as much of the pie as possible.

Jason Hsu:

Yeah. Before we go to Patrick, I wanted to give the audience a chance to ask questions too, so we reserved the last 10 minutes. If you have any questions you would like to ask, please think about it, but Patrick, please.

Patrick Wilson:

Well, thank you. Obviously MediaTek is a really big designer, creator of lots of chips all over the world. We care a lot about certainty in the regulatory environment and so we want rational certain regulatory environment because that helps us make big decisions about where to invest, where to do design and other things, but as a lifelong policymaker, I’ll put on that hat for a second and I’ll say, every time that an export control proposal comes from our good friend Jeff Kessler or people like Peter mentioned, those folks really, they know about our industry, but I would always put in front of them whatever is proposed, does it make it more or less likely that innovation will happen here? That has to be the starting point. We do want to have really deliberate national security focused export controls, but we also don’t want to drive innovation somewhere else. That’s just as an American. I’m biased and I want the innovation to happen here. I work for a Taiwanese company. They’re happy to do it there and they have been, but we’re in a competition and we want to create the right environment for innovation to happen here.

Luckily, this administration is very focused on deal making all across the administration. These are deal maker people and they get it. We’re out there fighting in the marketplace trying to win contracts, win sales and to be not impartial, if I were in the US government today, I would say if the question was rhetorically, what percentage of chip sales in the world do you want to be by America’s trusted allies in American companies? Well, the answer is all of them. As a policy maker, not as a company, we want them all to be MediaTek chips, but as a policy maker your answer is, we want all of the chips in the world to be trusted, reliable technology from the US or her close allies and partners. We want 100percent of the market. That’s not going to happen, but from a regulatory standpoint, that’s the outcome you’re shooting for, is that the greatest number of sockets, that’s how our industry talks about all the time. The greatest number of sockets plugged in with technology from trusted sources, which is a great outcome.

On the export controls piece, I can’t not pick up on the thread that Peter mentioned about people and the great thing is, having been in the industry so long, I’m kind of like the OG first lobbyist for the semiconductor industry. How awesome is it that we have this whole generation of young people? I look at my good friend Landon Heid and I think, they made a career out of this, being deep in the weeds on semiconductors and it’s such a huge advantage for us now because we have a whole group of policy makers who really know about the semiconductor industry and that has not always been true. It’s such a great place when you go in for a meeting and you’re not starting at, what is a semiconductor, which it used to be when I first started this job and now they’re like, let’s get to the meat of it. Let’s get the outcomes we want and that’s just such a blessing that I am grateful for that we have a lot of these experts who are serving our industry.

Jason Hsu:

Paul?

Paul Treadgold:

Yeah. I’ll pick up on a few things that folks have already mentioned. Number one, I would just echo the points that my colleagues here have made around clarity, certainty. Every slide, every presentation that we give internally at Tokyo Electron starts with a slide that says safety, quality, compliance and that compliance piece is incredibly important for us. To the extent that there is clear guidance certainty around all export controls, we will 100percent comply with the letter of the law, spirit of the law in all instances and I know that’s the same for the companies up here, so I just wanted to make that point.

I would point to, the second thing I’ll mention is, I think it’s actually a success story of what we’ve seen around the close collaboration that the US has had with Japan and the Netherlands in this area of export controls, this informal tri-lats dialogue to align export controls as much as possible. Export controls are a, we view that as a company, a national security issue that is best left to the governments to negotiate amongst themselves. Going back to my first point, we’ll comply with whatever rules they decide upon, but we are actively encouraging close collaboration between the governments that have jurisdiction over the countries where we have operations to do that close collaboration and alignment because we want there to be an equal level playing field and we think that’s natural and fair, so would encourage the Trump administration to continue that approach.

The third point I’d make is, as I said, that we view export controls to be a national security issue. Governments have access to the information that industry does not have. On the other hand, industry also has access to information about what life is like on the ground in various places around the world that the government may not have. We think there’s opportunity for a strong industry collaboration and partnership. How can government and industry work together to develop rules that are most effective and provide the maximum amount of clarity for industry players and then the last point I’d make and this was already echoed as well by John, is if you’re going to implement controls to prevent technologies going to certain markets and trying to slow down the development of markets that may be competitors on a global scale, it’s really, really, really important to, if you’re trying to widen that gap, to invest here in the US and in partners and allies to run faster because if you’re slowing somebody down, but you are just kind of maintaining your slow walking pace, then that’s not going to be the most effective strategy.

If you’re going to slow somebody else down, you better run as well in the interim. That applies to, obviously, the US, but also the development of close allies and partners like Japan, the Netherlands, Taiwan. Really bolstering and boosting up that entire collaborative ecosystem, so those best practices are shared among trusted partners.

Jason Hsu:

Yeah. One more question to panelists and we’ll go to the floor. President Trump has announced another wave of tariffs, this time is targeted on automotives and we understand that the industry serves all various aspects of business, including mobile phones, automotives, EV obviously is a big one. President Trump is likely to announce another wave on April 2nd, like whole spectrum tariffs announcement. Curious to know all of your thoughts that, are any of this tariffs regime is impacting your business and how would you as an industry player that is so integral and important current to build the United States core strength in technology leadership, to express your own views or concerns over this or is it even a concern to your business? Just quickly, maybe one or two minutes to share some bites on this.

Peter Cleveland:

TSMC has spoken to the White House and we’ve met with Secretary Lutnick on this subject and we’d like to make it a win-win for both sides both sides. And so that dialogue continues intensively in terms of the massive semiconductor fabrication and ecosystem that exists in Taiwan in terms of the exports out into the United States. And they’re listening. And so I think the dialogue will continue in a positive direction. It seems day to day in terms of how they adjust their policy and their outlook. So it’s not clear to us what’s going to occur on April 2.

Jason Hsu:

Yeah, anyone?

Patrick Wilson:

I think, granted, I’ll do history again. But two things to take away on the tariff as a background story, right? America has history with tariffs in the semiconductor industry. We had a huge fight in the 1980s again during the Reagan administration about tariffs with our friends in Japan. Japan was dominating the world at the time, and the US thought, “Even though we invented it here, we’re going to lose it,” because the unfair trade practices and the US went to work to dismantle tariffs for the benefit of. . . And America’s industry was rescued by creation of semi-tech and by creating a level playing field.

Because America’s view has always been, “If given a chance to fight it out in a fair fight, we’re going to win.” That has been America’s view historically, and so I’m very pleased to just remind people, people who are new to the trade space, that semiconductors transit, the world tariff-free. The president is very key on reciprocity. And I think that’s an important point, but to remember that semiconductors add a product category, they travel the world tariff-free to our close allies and around the world. And I think that’s important. I, like Peter, obviously we want to engage with the administration to help explain how we empower.

Think about our biggest customers, tiny companies. You may have heard of Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Meta, just some startups in the technology space. We provide chips to make all their products sold all around the world. And so we look at that as we’re empowering American companies to go and compete and win business around the world. And one of the frustrating things about tariffs is, remember, the president talks about make it in America For America, that’s a small part of the global market. You go ask Amazon or Google or any of our customers, do you just want to have customers in the US? Of course not.

Last year, 250 million cell phones sold in the US. In China, 800 million. Right? We’re America, we want to go and fight and get as many sales as we can, and so we should have the architecture in place that’ll let American companies go out and compete and win business around the world. That’s the story we’re going to tell. I don’t know how that will land. It’s a challenge. But these are deal-maker people, they get that. These American, big American tech companies, they want to go out and win business. And that’s what we are about is we’re about making our customers successful.

Whatever their consumer goals are, what they want to go sell, whether that’s Nvidia, our partner in the spark device for AI, or all the other thousands of American customers that we provide chips for, we want to help them go out and win. And we just want to have the right tariff or regulatory environment that makes it possible for our customers to win.

Jason Hsu:

Yeah. John or Paul, want to chime in on this?

Jonathan Hoganson:

No, I agree with all this. Look, it’s a global industry. I think we’re all invested, at least all of us here and the folks I talked to about making sure the United States sees that ecosystem rebuilt. And just as they think about tariffs going forward, I think it’s still out there as to how they’re going to impact the industry overall. But just we’re hopeful that it be viewed through that lens of what is going to ultimately be rebuilding the ecosystem here. What is going to be beneficial to making that happen as opposed to pushing us in the wrong direction. But it’s an ongoing conversation.

Jason Hsu:

Paul, anything to add to that?

Paul Treadgold:

The tariff conversation is probably best left to the US in our case, the Japanese government to negotiate directly. Just one point I would make is kind of going back to that point I made earlier around the importance of compliance. I think as these new tariff measures are coming out, and we saw this with the steel and aluminum tariffs recently, just making sure that it’s very clear to companies that are going to be subject to these tariffs, how to comply.

And to the extent that the tariffs may be asking for information that is not normally shared in customs process filings, making sure that the companies have time to collect that information, work with their suppliers so that we are paying the amount that we should be. So just would highlight that.

Jason Hsu:

We have about 10 minutes left and we’re just going to collect maybe two or three questions each time. And then each of you or whoever wants to answer. And so, please, when you ask a question, identify yourself and then ask question instead of a speech. We’ll go from this gentleman and then this gentleman here and this gentleman here. And then we’ll quickly go through the next round. Yeah, please.

Speaker 1:

Thank you. I’m Nury Turkel, I’m a senior fellow here at the Hudson Institute. We just published a policy memo on the issues that you discussed today focusing on the necessity for innovation investment goes to the domestic investment. And also we talked about the effectiveness of the export control measures over the years focusing on the diffusion rule. And I’d like to ask the panelists two question, if there’s any room for change or improvement or completely come up with something new with respect to the points made, or the enforcement measures included in the diffusion rule. And then two, what are the things that the policy-makers can do to foster domestic innovation?

Jason Hsu:

All right. Thank you. This gentleman here and then the gentleman on third roll. Yeah. Please.

Ray Wong:

Hi, Ray Wong here. My first question is for TSMC. As we know the investment credit under the CHIPS Act will be expired in 2026. So given the additional $100 billion investment, I wonder how much of the $100 billion investment will qualify the investment credit that will expire in 2026. And another question is for the media tech, have you aware of the cooperation between media, tech and ByteDance when it comes to AI accelerators? And if the cooperation is true, have you foresee any regulatory challenge from US given the fact that if the design is regarding the AI chips? Thank you.

Jason Hsu:

And, Ray. Ray, what’s your affiliation can you identify yourself?

Ray Wong:

Georgetown University.

Jason Hsu:

Okay, thank you. And this gentleman here on third row, please.

Jeffrey Krasnik:

First of all, thank you all for being here. My name is Jeffrey Krasnik. I’m just kind of curious with respect to the likelihood of a new tax bill in the fall, what two things, if you could put them in the tax bill, what two things have passed would you like to see within the tax bill, including I suspect, increased R&D.

Jason Hsu:

Okay, good. We’ll go to the next row. Okay? Yeah. Peter, you want to just start? I think there’s some questions.

Peter Cleveland:

Sure. I think the AI diffusion rule is subject to some change, and that was my understanding in speaking to David Fife and the others. And so there’s a complexity in terms of the multiple tiers and compute caps for certain countries that are equivalent in the second tier that the administration may think does not make sense. And so TBD, that’s not directly impactful on TSMC. So that’s my response there. Are you an undergrad at Georgetown?

Ray Wong:

Yeah.

Peter Cleveland:

Oh, I went to Georgetown. And I liked your question about the investment tax credit. So we would-

Ray Wong:

Sorry. If you can give us a forecast of how that. . . Whether it’s all by the investment credit and how that will impact the buying process that is given by Wendell.

Peter Cleveland:

Given by Wendell in January?

An undergrad at Georgetown and you’re asking about margin dilution. Okay. The investment tax credit is vitally important. P1, P2, P3 qualify for the 25percent ITC and will benefit from that. Going forward, we have spoken to the administration about statutory continuation of the credit. This is a 15, 20-year plan for all the companies, the entire ecosystem and the credit is essential.

And so including it in a tax extension that Mr. Krasnik was just mentioning is a good idea because semiconductors are the most complex product to make in the world, and it’s absolutely vital that the fastest, highest performing chips are made here. And that depends on continued collaboration with this administration and future administrations. And the form of that collaboration should take. . . Should be through extension of a credit in the code.

Jason Hsu:

I think there’s a question directed to MediaTek as well.

Patrick Wilson:

Well, I was going to take on another part of that-

Jason Hsu:

Yeah, please do.

Patrick Wilson:

. . . the question from the Hudson Institute, and I was going to say that it continues to be workforce development. The neglected problem that the government is not paying attention to is we have to get more engineers. And we’re excited to partner with Purdue University. For instance, we opened an office on the campus of Purdue, 50 feet from the engineering school. We opened a design center there in 2022 because we need to develop more talent.

And that’s certainly, I can foot stomp that all day. Specifically to the question about Chinese companies in collaboration, I will say that first of all, MediaTek is always going to follow the rules, always just like all the companies up here. Whatever the ground rules are that our Taiwanese government, which by the way, can I compliment them, they don’t get the same diplomatic treatment as our friends from Holland and from Japan.

But Taiwan has done exactly what the government has asked. And I can say that as a multilateral negotiator or whenever I was in Taiwan on behalf of the US government, the Taiwanese always were a partner and always said, “We’re going to do whatever is required.” And I think for us as a company, that’s our commitment as well, is we’re going to follow the rules with whatever companies are out there. I will say that, and this is a real takeaway, is that as an observer and an advisor to my own business, I often say that technology now, bundled in with the brilliant technology is another component. It’s a feature of every single piece of technology. And that’s trust. Trust is a part of the technology. The consumer wants to know that they trust their device, that it’s not going to be hacked, that their personal information that resides on it is trustworthy.

Our partners, the big companies that I mentioned, they want to know that our partner like MediaTek, we play by the rules, that we’re trusted, and we’re going to be a good collaborator. And so that’s a part of that. So whoever the customers are, whether they’re Chinese customers, American, European, we have all of those, we always start from we’re going to 100percent comply because that’s how the rules of the game are and we’re going to play by them.

But secondly is we’re going to bring trust to every relationship and it’s going to be transparent, it’s going to be open. When people ask questions about it, we’re going to answer them. In this particular case, which I mean, I don’t know if. . . I have not actually seen a story like that, but I would say that most of our customers choose us because we have ready-to-go commercial off-the-shelf technologies that they’re going to use in whatever cool guy thing they want to do. And that’s what they come to us about. And certainly, we do collaborate on software and other things.

But unlike some companies, we don’t make our products in China. We don’t. We don’t keep IP there because we have to follow the Taiwan rules, which are actually stricter. Investment talent, all of those things are very strict in Taiwan. So in addition to having to comply with US laws, whatever they are, we have to also comply with Taiwan laws from our place of headquarters. And they’re really tough. And I think a lot of Americans miss that, is that we’re complying everywhere we operate within the EU, in Japan, in Singapore, in Taiwan. We’re always complying, and obviously, that’s a big part of my job.

Jason Hsu:

Yeah. Thank you, Patrick. We have time for two questions, Veronica and this here.

Veronica Pollack:

Hi, I’m Veronica Pollack, vice president at the Daschle Group, a public policy firm here in DC. Loved hearing all of this, and thank you for speaking in layman’s terms for some of us who aren’t as much into the weeds as you are. I’m curious to know, you’ve talked about some of the obstacles in the investments in the US. We talked about workforce, there’s a robust, I guess, discussion I’ll say on energy and natural resources here in the us and I’m wondering what role that plays in your investments in looking long-term into the energy. I’m thinking grid reliability, natural resource, access to water, for example. What are your thoughts on that? What’s your level of engagement on that and this discussion that’s going on right now?

Jason Hsu:

And this lady here.

Anne Vroom: