Introduction

For decades, the United States has sought to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons among friends and foes alike. This goal, however, may be at risk. While global challenges multiply, regional adversaries like North Korea pose an increased threat to US allies. In particular, South Korea appears to doubt the credibility of US extended deterrence. Seoul has sought to strengthen deterrence and even weighed the benefits of acquiring its own nuclear weapons.

This report uses international relations theory, historical research, survey data, and original interviews with South Korean experts to examine (a) nonproliferation’s role in US grand strategy, (b) the relationship among nonproliferation, extended deterrence, and assurance, and (c) growing challenges to these three missions, particularly on the Korean Peninsula. It then suggests an approach for the United States to address these challenges.

Nonproliferation remains important to national security. But the United States should consider it among other national security priorities. Managing priorities is a matter of continually evaluating risks and benefits. The United States can best do so through a series of measures that improve extended deterrence and assurance to manage the risk that allies pursue nuclear weapons.

New Challenges to Nonproliferation

US policy on nonproliferation has been consistent since the Cold War. President George H.W. Bush committed to “more effectively discourage the spread of nuclear weapons.” President George W. Bush declared that “every civilized nation has a stake” in stopping proliferation. President Donald Trump reaffirmed that “nonproliferation is crucial to maintaining regional security and avoiding conflict and military competition.” Similarly, President Joe Biden’s 2022 National Security Strategy commits to addressing the “existential threat posed by the proliferation of nuclear weapons,” including through the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

But some analysts believe a worsening security environment is jeopardizing Washington’s nonproliferation goals, including preventing US allies from acquiring nuclear weapons. David Trachtenberg argues that about 30 states rely on US extended deterrence and that, without credible US assurance, some may develop their own nuclear weapons. Jennifer Bradley writes that nonproliferation was the “key driver” of extended deterrence, but regional deterrence challenges have created assurance gaps, creating proliferation risks. Michaela Dodge finds that US allies in Europe and Asia question the credibility of extended deterrence because US military capabilities cannot cover both theaters simultaneously. She and Keith Payne argue that persistent capability gaps could “drive a cascade of nuclear proliferation . . . as some allies feel compelled to find independent means of deterrence.” The challenge to nonproliferation appears significant.

Nonproliferation and Grand Strategy

To determine how the United States should approach new nonproliferation challenges, it is important to consider nonproliferation’s historical role in US grand strategy.

This section reviews a dozen arguments on both sides of the nonproliferation debate. It focuses on what James Schlesinger, then an analyst at the RAND Corporation, described as the “strategic consequences of nuclear proliferation”—how the spread of nuclear weapons affects military power and national security. This keeps focus on the core of US grand strategy and allows an evaluation of arguments in common terms.

Arguments for Nonproliferation

Below are arguments for the importance of nonproliferation in US grand strategy.

1. Entangling Alliances

Argument. Nuclear allies are more likely than nonnuclear ones to entangle the US in conflicts abroad, with greater potential consequences.

The United States is historically averse to foreign entanglements. Allies could present the risk of “chain-ganging,” when an ally drags another into a war. Nuclear allies can use or threaten to use nuclear weapons and drag the United States into a war, intentionally or not. Managing nuclear escalation among multiple parties is more complicated because it introduces so-called second centers of decision for nuclear use. During the Cold War, Pakistan and South Africa had “catalytic nuclear postures,” which sought to catalyze superpower intervention on their behalf.

Assessment. The US cannot eliminate the risk of entanglement without abandoning its alliances. But Washington can limit this risk by discouraging allies from acquiring nuclear weapons. Having a greater number of nuclear allies acutely increases the risk and potential consequences of chain-ganging. To avoid being dragged into a war it does not wish to fight, and to maximize options for when and how US policymakers engage in conflicts far from America’s shores, the United States should continue to oppose proliferation by allies.

2. Alliances and Asymmetry

Argument. Allies that depend less on US security are less inclined to consider US security interests in their actions and may be more emboldened to take risks that lead to conflict that affects US interests.

Because US allies have similar but unidentical interests, the United States has been cautious about their pursuing independent foreign policies. Therefore, the US has designed certain alliances to favorably influence regional dynamics. As a 1957 Central Intelligence Agency memorandum describes, nuclear allies could “take more vigorous actions in support of individual national interests.” Nuclear allies may be more emboldened to pick fights and harm US interests in the process.

Assessment. The United States should preserve its regional influence. US alliances are partnerships, not protectorates. The United States is wise to honor the sovereign decisions of its allies. But Washington has far-flung security interests, and its policies should promote them, even if they are at odds with allies. To promote alignment with its friends, the United States should support nonproliferation toward allies.

3. Dividing Labor

Argument. Nuclear allies may be less inclined to make necessary investments in conventional defenses, seeing nuclear weapons as economical substitutes.

In recent years, the United States has pressed its allies to assume more responsibility by investing in conventional defenses. As explained in argument 2, Washington may have less ability to promote alignment with its friends, undermining its effort to encourage conventional investments. Nuclear weapons, though, cannot fully substitute for conventional defenses, and weak conventional defenses could increase the risk of deterrence failure and therefore the pressure for US intervention.

Assessment. The United States should continue to emphatically encourage its allies to invest in conventional defenses. A division of labor in which allies take more responsibility for their conventional defenses, while the United States remains primarily responsible for nuclear deterrence, appeals to comparative advantage. To be sure, a better division of labor does not preclude shared responsibilities, such as US conventional strike and allied participation in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s nuclear mission. Washington should oppose proliferation and instead encourage its allies to improve their conventional defenses, thus enabling the United States to adapt its key forces across geographic regions as the strategic threats require and reducing the risk of deterrence failure.

4. Reducing Strategic Risk

Argument. Proliferation makes nuclear use more likely.

The United States has sought to reduce escalation risks in wars abroad, largely to avoid nuclear use against it. Nuclear use could be deliberate or by accident, as nuclear weapons stewardship has proven expensive and difficult. As more states acquire nuclear weapons, the logic goes, nuclear use becomes more likely; as nuclear use becomes more likely, the likelihood of nuclear use against the United States also increases.

Assessment. Given the potential consequences, the US should seek to prevent even small increases in the likelihood of nuclear use. To reduce strategic risk, especially the use of nuclear weapons against it, the United States should seek to limit the number of states with nuclear weapons.

5. Proliferation Cascades

Argument. Proliferation by one state could begin a cascade of proliferation.

The United States has historically worried that proliferation by one state would spur further proliferation to the “Nth country.” The NPT and related efforts by the United States and its allies have arguably stemmed proliferation. But regional dynamics could prove more unstable. One state could acquire nuclear weapons and precipitate a cascade of proliferation. For instance, if Iran or South Korea acquired nuclear weapons, some fear that Saudi Arabia or Japan, respectively, would feel compelled to follow suit.

Assessment. One case of proliferation does not necessarily create a domino effect. Acquiring nuclear weapons is a difficult choice, and there are numerous reasons why only a few states have done so. In South Korea’s case, the states that would react most strongly—North Korea, China, and Russia—have already built up their nuclear arsenals. Still, if South Korea acquires nuclear weapons, Japan would be more likely to do the same. Tokyo’s security is closely tied to regional dynamics, so it is likely to feel pressure to proliferate. As described, this would harm US interests. While proliferation cascades are not simple or certain, Washington should still discourage allies from pursuing nuclear weapons.

6. Great Power Diplomacy

Argument. Proliferation by US allies could lead to competition in nuclear assistance programs among great powers.

Scholars have argued that the United States pursued nonproliferation to improve great power relations. During the Cold War, Washington worried that proliferation by its allies would encourage the Soviets to assist their allies’ nuclear programs in turn. After the Cold War, Russia cooperated with the United States in preventing the spread of nuclear weapons to both former Soviet states and rogue states. But today the United States does not have a cooperative partner in Russia or China. While nonproliferation may not improve great power relations, proliferation could make them worse. Russia and China could seek to counter nuclear weapons in the hands of US allies through increased threats and capabilities of their own or further aid to US adversaries, such as North Korea.

Assessment. This argument is not fully persuasive. China and Russia are already adversarial, so US support for proliferation among allies is unlikely to meaningfully worsen great power relations. Indeed, both China and Russia have frustrated nonproliferation efforts in recent years, especially with their support of North Korea. The United States cannot expect to find a constructive partner in either anytime soon. So while US adversaries will react poorly to allied proliferation, Washington should not be hostage to their reaction. Instead, Washington should underscore to China and Russia that their choices can have consequences they do not desire, but which the United States cannot entirely control.

7. Undermining Efforts

Argument. Proliferation among allies would undermine nonproliferation toward adversaries.

The United States has long maintained that North Korea must surrender its nuclear weapons and that Iran must never obtain them. US diplomacy has secured nonnuclear states’ support for these nonproliferation goals, such as through sanctions enforcement. But these cooperative states may become less willing to support US nonproliferation efforts toward adversaries if Washington appears to endorse proliferation among its allies.

Assessment. Reversing the US position on nonproliferation might harm its diplomatic efforts to constrain adversaries. States that perceive that the United States selectively exercises its legal and normative obligations will probably be more reluctant to support US initiatives. US nonproliferation goals for North Korea and Iran are already difficult to obtain; losing further support would make them more so.

Arguments against Nonproliferation

Below are arguments for decreasing US focus on nonproliferation.

8. Geopolitics vs. Nonproliferation

Argument. The United States should choose geopolitics over nonproliferation to prevent any aggressor from dominating an important region.

Some strategists acknowledge that the US has an interest in nonproliferation but advocate choosing geopolitics over it. Preventing a great power from achieving regional dominance, this argument goes, is more important than stopping the spread of nuclear weapons. If the United States cannot deter China while keeping some of its alliance commitments, Washington should accept, if not encourage, its allies’ pursuit of nuclear weapons. Indeed, great powers have even treated “proliferation as policy” when it served their interests. In other words, geopolitics should trump nonproliferation.

Assessment. The United States does need to balance geopolitics and nonproliferation, especially when US priorities of interests diverge from those of its allies. For example, the United States is focused on deterring the threat from China, which is its pacing threat, and managing the threat from North Korea. South Korea is focused on the threat from North Korea, which is existential for South Korea. Striking the right balance is a matter of judging risk and benefit (for more on this, see “A Better Approach for Managing Risk” below). Because the risks of proliferation remain greater than the benefits, the United States can and should maintain its nonproliferation goals while seeking to deter China and manage the North Korean threat.

9. Come Home, America

Argument. Having more nuclear allies would allow the United States to retract its defense commitments and husband its resources.

Defending US allies and partners is a heavy and growing burden. The United States maintains a global defense posture that consumes significant resources with material trade-offs. If US allies acquire nuclear weapons, some strategists argue, the United States could retrench, shedding its global commitments and saving blood and treasure to defend the homeland.

Assessment. Retrenchment would transform US grand strategy well beyond its nonproliferation agenda. It would undo the alliances and international engagement that enable US national security and economic prosperity, therefore degrading American strength. Moreover, Washington would surrender its influence over regional dynamics, including its ability to prevent nuclear escalation abroad. Retrenchment would accept significant risks with possibly global consequences. US global defense commitments are costly—but necessary, especially in an era with significant threats to US security interests.

10. Atomic Alarmism

Argument. Nonproliferation advocates engage in undue alarmism, and the United States does not need to pursue costly nonproliferation policies.

Nuclear proliferation has, as President John F. Kennedy put it, “haunted” the United States since the beginning of the Atomic Age. The 1964 Gilpatric Committee warned that the world was approaching a “point of no return” in curbing nuclear proliferation. Although proliferation was a perennial concern during the Cold War and after, there has been no “rapid and uncontrolled spread” of nuclear weapons. From this, some strategists conclude that anxiety about nuclear proliferation is excessive.

Assessment. As noted, proliferation in one case does not necessarily create a domino effect. But given the consequences of proliferation, those arguing that nonproliferation efforts are unnecessary face a higher burden of proof. The United States is right to be anxious about runaway proliferation, however remote a possibility it is.

11. More May Be Better

Argument. Nuclear weapons deter aggression, and their gradual spread could stabilize international politics.

Scholars have argued that nuclear deterrence contributed to the “long peace” between the United States and the Soviet Union. Nuclear weapons increase the risk and cost of conflict, so some scholars believe a small number of them can credibly deter aggression. According to this argument, although extending nuclear deterrence to allies is difficult, direct deterrence is easy, and by deterring aggression, the gradual spread of nuclear weapons to allies could stabilize international politics. For example, some argue that South Korea could restore parity on the peninsula with an arsenal of 100 nuclear weapons, effectively deterring North Korea.

Assessment. The spread of nuclear weapons would constrain US freedom of action, potentially limiting Washington’s ability to affect regional dynamics and promote its global interests. Still, it might be possible that a nuclear South Korea could more credibly deter North Korea than the sole threat of US retaliation, given the current posture of US nuclear forces, which are no longer stationed on South Korean soil. To be sure, the United States credibly extended deterrence to NATO during the Cold War. But the US had forward stationed nuclear forces in NATO territory and nuclear sharing arrangements with NATO allies. The US has neither with South Korea.

12. Nuclear Hypocrisy

Argument. The United States is wrong to deny sovereign, democratic states the freedom to make their own security choices.

Some argue that US nonproliferation policy is hypocritical and, on those grounds, it should be reversed. Washington guards its own arsenal from disarmament and has allowed only certain allies to develop their own deterrents. Critics charge that the United States, through its rigid nonproliferation policies, denies sovereign, democratic allies the freedom to make their own security choices.

Assessment. This argument is unpersuasive. The nonproliferation regime separates states with nuclear weapons from those without them. US support for nuclear allies in NATO and simultaneous opposition to proliferation in East Asia reflects the realities of international politics. US security interests are not uniform; its foreign policy will not be either.

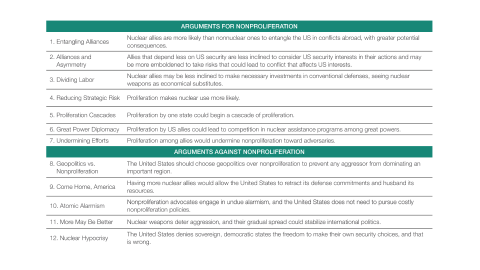

Assessment

Many—but not all—arguments for nonproliferation are persuasive (see table 1). Some opposing arguments also have a degree of merit. Ultimately, we believe that nonproliferation remains an important national security goal, and the United States ought to implement strategies most likely to bolster nonproliferation goals.

Primarily, proliferation would increase the risks and consequences of entanglement for the United States. It would increase the likelihood that the US would have to intervene to prevent nuclear escalation or defend an emboldened ally. Furthermore, this policy would limit US influence over regional dynamics and diminish Washington’s ability to promote alignment among allies. Finally, proliferation among US allies may make them more reluctant to invest in their conventional defenses, undermining efforts to promote a more effective division of labor and weakening deterrence. Finally, proliferation would make the use of nuclear weapons more likely, including against the United States.

Still, nonproliferation is a means rather than an end of US grand strategy. The United States should continually assess its geopolitical aims and nonproliferation goals, a process that is a matter of judging risks and benefits. Washington can and should uphold nonproliferation while prioritizing geopolitics, especially deterring China from major aggression.

Table 1: The Nonproliferation Debate

Source: Authors.

Extended Deterrence, Assurance, and Nonproliferation

US policy documents describe a connection among extended deterrence, assurance, and nonproliferation, including toward allies. The 2022 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) states that “extended deterrence contributes to US nonproliferation goals by giving allies and partners confidence that they can resist strategic threats and remain secure without acquiring nuclear weapons of their own.”

Earlier reviews make the interdependence of extended deterrence, assurance, and nonproliferation explicit. The 2018 NPR states that “effectively assuring allies and partners . . . enables most to eschew possession of nuclear weapons.” As the 2010 NPR explains, “the potential for regional aggression . . . raises challenges not only of deterrence, but also of reassuring US allies and partners.” Failing to assure them “could lead to a decision by one or more nonnuclear states to seek nuclear deterrents of their own.” Separately, the 2023 report by the bipartisan Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States (on which Rebeccah Heinrichs served) reinforces this connection: “US strategic posture also serves to assure allies. . . . As a result, many allies perceive no need to develop their own nuclear weapon capabilities, which is in the US national security interest.”

These claims have broad support from experts outside government. The nonproliferation regime, Susan Koch explains, represents a bargain between nuclear states and their nonnuclear allies. These allies forego proliferation in exchange for assurance. Historically, states that received assurance eschewed nuclear weapons; states that did not receive assurance pursued them. “This double correlation,” argues Bruno Tertrais, “suggests that such guarantees are critical.” Other studies have shown that states that perceive their allies to be unreliable, and the costs of proliferation to be low, are more likely to pursue nuclear weapons. Assuring allies that US extended deterrence is credible promotes nonproliferation.

But the specific requirements of assurance are less clear. In the early Cold War, US forces in Europe had to both deter Soviet aggression and assure NATO “that the benefits of military action, or preparation for it, will outweigh the costs,” as Michael Howard explains. During the Cold War, David Yost argues, the visible presence of US nuclear forces assured NATO that its alliance commitment was credible and that proliferation was unnecessary. But the requirements of assurance appear more difficult than those of extended deterrence. Former United Kingdom Defense Minister Denis Healey said that it took “only 5 percent credibility of American retaliation to deter the Russians, but 95 percent credibility to reassure the Europeans.” Clark Murdoch and others observe that neither extended deterrence nor assurance is a “lesser included case” of the other; rather they are “symbiotic.” Capabilities are crucial to making extended deterrence credible, but assurance also relies on the nonnuclear state’s perception of its partner’s commitment. Neither discourages proliferation without the other.

After the Cold War, studies found that the requirements of assurance were broad and changing. They ranged from extensive consultations to effective missile defenses to strong hedges against arms reduction. As the US Strategic Command advisory group observed, “We cannot measure our nuclear forces solely against the standards that satisfy our immediate [extended deterrence] purposes; we must also consider the standards applied by those to whom we wish to extend a credible assurance.” The 2023 strategic posture commission’s report extends this observation to warn that “any major changes to US strategic posture, policies, or capabilities” will affect assurance. South Korea is a useful case study of this interdependence.

Nuclear Weapons and South Korea

The United States first deployed nuclear forces to South Korea in January 1958, roughly four years after Washington’s first deployment of nuclear weapons to Europe and the armistice that ended fighting in the Korean War. Though US nuclear forces remained in South Korea for 33 years, they did not eliminate the risk of proliferation.

South Korea’s Nuclear Weapons Program, 1969–75

During the Cold War, South Korea’s perception of US retrenchment sparked the country’s interest in nuclear weapons. In 1969, President Richard Nixon announced the Guam Doctrine, which enjoined Asian allies to assume more responsibility for their defense. In 1970 the United States negotiated the withdrawal of 24,000 US troops from South Korea. In 1972 Washington announced a rapprochement with the People’s Republic of China. The United States also delayed $1.5 billion of security assistance to South Korea during this period.

Although the US and South Korea had signed a mutual defense treaty in 1953, and the US deployed conventional and nuclear forces to the peninsula, South Korea began to question US reliability as an ally. While South Korea had developed civil nuclear programs in the 1950s, South Korean President Park Chung Hee initiated a covert nuclear weapons program. In 1970 South Korea began constructing a light water reactor and conducting weapons research and in 1975 Seoul agreed to purchase nuclear infrastructure from France and Canada.

The US government became more attentive to proliferation risks after India’s 1974 nuclear test. A State Department cable to the US embassy in Seoul warned that South Korea’s nuclear program would have a “major destabilizing effect” on the region. The Soviet Union and China, for example, could begin to support North Korea’s nuclear weapons program. Because nonproliferation was US policy, the State Department’s objective was to “inhibit to the fullest possible extent any development” of nuclear weapons by South Korea. The embassy agreed, recommending an “early, direct, and firm approach.” The US ambassador conveyed these concerns to South Korean officials, warning of an “escalating impetus [for] North Korean efforts to obtain nuclear technology” from the Soviet Union and China.

Secretary of State Henry Kissinger agreed to intervene with South Korean leaders and block the sale of nuclear infrastructure. Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger underscored to President Park that the United States “attached extreme importance to the NPT” and South Korean adherence to it. The United States also threatened to withdraw all US forces from the peninsula and impose economic costs on its ally. South Korea relented for a time. But a few years later, Seoul restarted its nuclear program when President Jimmy Carter announced that he would withdraw US conventional and nuclear forces from South Korea.

These dynamics recurred elsewhere throughout the Cold War. For example, China’s October 1964 nuclear test motivated Taiwan to pursue a nuclear weapons program. That accelerated during US-China normalization a decade later. In response, the United States threatened to cease civil nuclear cooperation with Taiwan, which also depended on US arms sales and trade. Washington compelled Taipei to adopt stringent nonproliferation requirements. As in South Korea, the United States pursued various “strategies of inhibition,” as Francis Gavin has called them, to manage proliferation risks.

US Nuclear Deployments in South Korea, 1953–91

When the Cold War ended, about 100 US nuclear weapons remained in South Korea. While the number and kind of US forces fluctuated over decades, only three systems served for the entire deployment: 155mm howitzers, gravity bombs, and surface-to-surface missiles.

The United States removed its nuclear weapons from South Korea while retracting its global nuclear posture for the post–Cold War world. In September 1991, President George H.W. Bush announced the Presidential Nuclear Initiative (PNI). The PNI eliminated ground-launched theater nuclear forces and removed tactical nuclear weapons from surface ships, attack submarines, and land-based naval aircraft bases. While the PNI focused on the Soviet Union, the United States also withdrew its nuclear forces from South Korea by December 1991. That included gravity bombs not covered by the PNI, “in part because the US military no longer thought that the nuclear bombs were necessary to defend South Korea,” according to a press report.

For its part, South Korea supported the removal of US nuclear weapons. Doing so was supposed to remove an irritant from the perspective of North Korea and encourage engagement with North Korea over reunification and its nascent nuclear program. Still, the United States would keep conventional forces on the peninsula and South Korea would remain under the US nuclear umbrella.

Increasing Threats from North Korea

North Korea’s threats toward the south have increased in the past four years. Kim Jong Un has stated that South Korea is a “hostile” state, rather than one of “fellow countrymen,” and threatened to “subjugate” South Korea in a war. North Korea’s growing hostility and increasing capabilities have raised the specter of conflict—and proliferation.

In 2022 Kim declared that North Korea will never denuclearize. According to the US intelligence community, “Kim almost certainly has no intentions of negotiating away his nuclear program, which he perceives to be a guarantor of regime security.” Indeed, in 2024 Kim declared that North Korea will “exponentially increase” its nuclear arsenal. North Korea possesses about 50 nuclear warheads and sufficient fissile material to produce up to 90, according to open-source analysis. Some analysts have speculated that North Korea will conduct a seventh nuclear test in the coming months, which would be its first since 2017.

In 2021 Kim announced several programs that would diversify North Korea’s arsenal, including strategic and tactical nuclear warheads, precision strike and hypersonic capabilities, solid-fuel rockets, and submarine-launched ballistic missiles. Since 2021 North Korea has tested nearly 150 missiles, including nearly a dozen nuclear-capable intercontinental ballistic missiles. If North Korea achieves an operational capability to deliver intercontinental-range nuclear strikes, it can hold the US homeland at risk. By deterring the United States from intervening in South Korea’s defense, North Korea could “decouple” the alliance.

North Korea has also deepened its cooperation with Russia while Moscow is pursuing an aggressive revanchist foreign policy agenda that threatens US partners and allies. Pyongyang and Moscow signed a mutual defense pledge in June 2024, and North Korea has sent 10,000 troops to support Russia’s war in Ukraine. US Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM) Commander Admiral Samuel Paparo and NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte have recently suggested that, in return, Russia might support North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs through technology transfers.

Growing Proliferation Risks in South Korea

South Koreans want to strengthen the credibility of nuclear deterrence. Most South Koreans think North Korea presents an existential threat and that China threatens their national security and that the threat from China will grow. In February 2022, the Chicago Council on Global Affairs found that 71 percent of the South Korean public supports the development of their own nuclear weapons, and that 56 percent of the public supports the deployment of US nuclear weapons in South Korea. But when asked to choose between an independent deterrent and US deployments, 67 percent preferred an independent deterrent.

In June 2023, President Yoon Suk Yeol speculated that, if the United States does not sufficiently bolster the credibility of its extended deterrent by redeploying nuclear weapons, South Korea could acquire its own nuclear deterrent. In June 2024, the Institute for National Security Strategy, a think tank based in Seoul, suggested that South Korea should consider requesting the deployment of US nuclear weapons, entering nuclear-sharing arrangements, and developing an independent deterrent. In September 2024, South Korean Defense Minister Kim Yong-hyun stated that an independent deterrent is “among all possible options” for responding to North Korea.

However, South Korean public support for developing nuclear weapons ebbs and flows but has been high for some time (see figure 1), even as most South Koreans remain confident in US extended deterrence. These findings appear inconsistent with the expectation of increased US extended deterrence and satisfied assurance requirements. The apparent inconsistency could be understood by differentiating whose views among the South Korean citizenry one is assessing. According to the Center for Strategic and International Studies, only 34 percent of South Korean elites, that is, those in government or with expertise in providing South Korean national security, favor an independent deterrent and want the United States to withdraw ground forces from South Korea. Still, South Korean security experts suggested that elite confidence in US extended deterrence, while higher than the public, is also declining. Collectively, these findings suggest that the risk of South Korean proliferation is real if not yet critical.

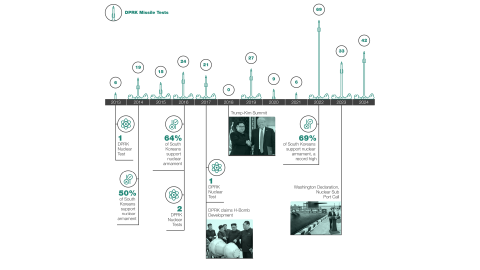

Figure 1: Timeline of North Korean Threats, US Actions, and Changing South Korean Public Opinion

Sources: Korea Institute for National Unification (KINU), CNS North Korea Missile Test Database, BBC.

Assuring South Korea

The United States has taken notice of increasing extended deterrence and assurance requirements for South Korea, a treaty ally. As then Acting Assistant Secretary of Defense for Space Policy Vipin Narang stressed, the US–South Korea relationship is a “nuclear alliance.”

However, consistent with US declaratory policy, the United States maintains calculated ambiguity about how exactly it would respond to aggression against South Korea. The Washington Declaration, announced in April 2023, said that “any nuclear attack by the [Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK)] against the [Republic of Korea (ROK)] will be met with a swift, overwhelming and decisive response.” This means that the United States could choose a nuclear or nonnuclear response to a large-scale conventional, chemical, biological, or nuclear attack by North Korea. As expected, interviews indicated that South Koreans are more confident in US extended deterrence against conventional attacks than nuclear ones. Some South Koreans have expressed the desire for an unambiguous policy, a so-called nuclear for nuclear commitment, without success. But the United States has been explicit that “there is no scenario in which the Kim regime could employ nuclear weapons and survive.”

The Washington Declaration also reaffirmed an “enduring and ironclad” alliance commitment and South Korea’s nonproliferation obligations. Washington and Seoul established the biannual Nuclear Consultative Group (NCG) to discuss nuclear and strategic planning, conventional-nuclear integration, and exercises, simulations, and trainings, among others. As of January 2025, the NCG has met four times and issued the US-ROK Guidelines for Nuclear Deterrence and Nuclear Operations on the Korean Peninsula. South Korean experts highlighted the NCG because their “lack of confidence in US extended deterrence arose from the concern that [it] depends on a one-way decision by the US, and [South Korea] does not have any voice or role for deterrence.” These experts also underscored the importance of conventional-nuclear integration in joint planning.

Beyond the NCG, Washington and Seoul committed to strengthening existing consultations such as the Extended Deterrence Strategy and Consultation Group (EDSCG). As of September 2024, the EDSCG has convened five times. In addition to expanding and deepening military cooperation, the US will “enhance the regular visibility of strategic assets to the Korean Peninsula.” A conventionally armed US attack submarine made a port call in South Korea in June 2023, as did a US nuclear-armed ballistic missile submarine in July 2023. Although the latter visit was largely symbolic, it was significant as the first such visit since 1981. Still, expert interviews suggested that the Washington Declaration improved but did not eliminate doubt in US extended deterrence.

North Korea’s growing ability to threaten the United States and South Korea could weaken both extended deterrence against Pyongyang and assurance of Seoul. Washington should take seriously the increased likelihood of South Korean nuclear proliferation. During the Cold War, the US–South Korea alliance endured similar challenges, but the United States remained committed to nonproliferation. The final section will outline an approach for improving extended deterrence and assurance amid new challenges.

A Better Approach to Managing Risk

This report has reviewed (a) the role of nonproliferation in US grand strategy, (b) the interdependence of nonproliferation, extended deterrence, and assurance, and (c) new risks to proliferation in South Korea. This section describes a balanced approach for managing the proliferation risks by improving extended deterrence and assurance.

The United States cannot assure allies if it cannot deter attacks against them. Extended deterrence requires military capabilities to prevent aggressors from achieving their objectives and impose costs on them. US military posture should be a mix of forward conventional forces, theater and homeland missile defenses, and limited nuclear capabilities to deter escalation. The United States should also preserve the credibility of its commitments and communicate the consequences of aggression. Still, extended deterrence is necessary but probably insufficient for assurance. Assuring allies that US commitments are credible may be more difficult than deterring adversaries. Assurance also requires consistent policy, regular diplomatic consultations, and close military coordination. It may also require a visible military presence.

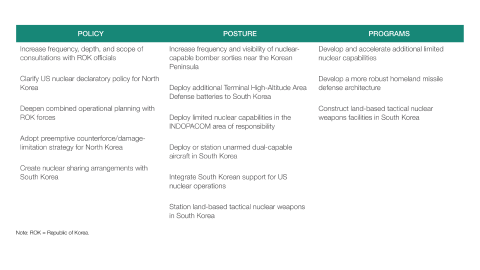

Whether in geopolitics or nonproliferation, the United States should not take on undue risk. The approach below lends itself to a continual assessment of risks and benefits. To balance priorities, this approach favors broadly effective actions that bolster both extended deterrence and assurance on the Korean Peninsula without detracting from America’s global demands. Because assurance is more difficult than extended deterrence, this approach also favors low-cost actions to assure allies. Table 2 lists some of the options to take as the risks and benefits call for them. The US should prepare some of these options now so that it can exercise them when needed. Washington can start by consulting regional allies, identifying capability gaps, and assessing program feasibility.

Policy

The United States should follow through on consultations under the Washington Declaration. These meetings with South Korean officials can serve as a forum for understanding extended deterrence and assurance requirements on the peninsula. The United States can increase the frequency, depth, and scope of these engagements depending on their urgency. Policymakers should also deepen combined planning for nuclear operations with South Korea as limits on sharing intelligence allow. These activities are a small investment with high return.

Similarly, the United States should sharpen its strategic messaging. For instance, US statements could emphasize the role of US nuclear weapons in deterring strategic attacks against allies. That would be consistent with current declaratory policy. The United States could also signal possible responses to a North Korean attack, such as preemptive strikes on North Korea’s nuclear capabilities to limit damage to South Korea and itself.

Posture

The United States should strengthen its regional posture. It can increase the frequency and visibility of nuclear-capable bomber sorties through bomber task force missions. These missions would be timed to respond to indications and warning (I&W) of threats by North Korea. The US can deploy additional Terminal High-Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) batteries to South Korea as North Korea’s ballistic missile capabilities grow. And Washington should deploy limited nuclear capabilities in the INDOPACOM area of responsibility to improve extended deterrence.

The United States should also prepare to periodically deploy or permanently station dual-capable aircraft in South Korea. Though unarmed, these aircraft would demonstrate US preparations to conduct limited nuclear missions. Having these capabilities in theater would improve extended deterrence, and their visible presence would bolster assurance. Moreover, these preparations would enable the United States to take further actions like integrating South Korean support for US nuclear operations or stationing US nuclear weapons in South Korea.

Programs

The United States should proceed with, and accelerate, the development of complementary nuclear capabilities that could be deployed nearer to the threatening adversary, such as the nuclear-armed sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N). US policy requires that its homeland missile defenses confidently “stay ahead” of North Korea’s long-range delivery systems. Developing layered homeland missile defenses would also increase the credibility of US extended deterrence and assurance by reducing America’s vulnerability to coercion.

The United States could also prepare to construct storage facilities for land-based tactical nuclear weapons in South Korea while it decides whether to deploy them. The presence of US nuclear weapons is likely to enhance extended deterrence and assurance. Moreover, it would not diminish US capacity in other capabilities that are few but in high demand, like submarine-launched ballistic missiles or penetrating bombers. Although theater-range ballistic and cruise missiles are ideal for this regional nuclear mission, nuclear gravity bombs could likely deploy more quickly.

A facility construction program in South Korea would be analogous to efforts underway in the United Kingdom. The United States withdrew its nuclear weapons from Royal Air Force Lakenheath Station in 2008, even as it hosts US Air Force units and personnel. But Washington is reportedly contributing to modernizing the air base’s nuclear weapons storage facilities. It received $50 million in fiscal year 2024, considerably more than facility construction programs in the 1990s and modernization programs in the 2000s. This serves as a reminder that not only is becoming a nuclear weapons state a costly initial decision, but maintaining safe and credible nuclear weapons capabilities is also an ongoing and costly endeavor. But as an official review concluded in 2008, stationing US nuclear weapons abroad is valuable to assurance, and the cost of nuclear stewardship relative to the catastrophic risk it seeks to prevent is “low and worth paying.”

Conclusion

The United States opposes the spread of nuclear weapons, even to US allies, for good reason. Primarily, nonproliferation (1) mitigates the risks and consequences of entanglement for the United States, (2) preserves US influence in regions where there is a high risk of conflict, (3) encourages allies to make conventional investments to deter war, and (4) reduces the risks of an employment of a nuclear weapon. Still, the United States should prioritize nonproliferation among other security interests, a process that is a matter of evaluating dynamic risks and benefits.

Extended deterrence and assurance have been America’s most successful means of achieving its nonproliferation goals. By assuring allies that extended deterrence is credible, the United States limits the risk of proliferation. But North Korea’s increasing military capabilities, especially the potential ability to hold the US homeland at risk, could weaken confidence in US extended deterrence. As global demands on the United States grow, the requirements to assure South Korea and thus limit the risk of proliferation will also probably increase.

The United States can best manage proliferation risks by improving extended deterrence and assurance. It has a number of policy, posture, and programmatic options to take, as the risks and benefits of nonproliferation call for them. While the United States continues to collaborate and follow through with its commitments under the Washington Declaration, prudence requires additional US preparation. We recommend the United States prepare to deploy or station dual-capable aircraft and construct nuclear weapons storage facilities in South Korea. As security on the Korean Peninsula deteriorates, the US needs to get started to provide the president of the United States this option in a timely manner.

Table 2. US Options for Enhancing Extended Deterrence and Assurance on the Korean Peninsula