Takeaways

- Though not a mutual defense alliance, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) remains the most important multilateral security structure in Central Asia that includes both Russia and China.

- Participating in SCO exercises provided the Chinese military with some of its first opportunities to rehearse power projection capabilities.

- The SCO has ceased holding its large Peace Mission series of exercises; other drills occur but less regularly.

- Despite differences regarding the SCO and the organization’s declining relative importance to Russia and China, the two countries have sustained a robust security partnership within the organization and in Central Asia.

Executive Summary

Though the SCO is not a traditional mutual defense alliance, many Sino-Russian military exercises with Central Asian partners have occurred under its auspices. These drills helped develop contacts, improve operational proficiency, enhance interoperability, and demonstrate deterrence capabilities to external observers. The SCO also established the first military confidence-building measures and multilateral counterterrorism networks among the Russian, Chinese, and Central Asian governments. Yet, since Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the SCO has ceased holding its biannual Peace Mission series of large multinational military exercises while continuing other drills on an irregular basis.

The Russian government welcomes the SCO as a prominent non-Western multinational structure that can advance its regional diplomatic, economic, and security goals. Participating in the SCO elevates Russia’s diplomatic status, helps it pursue economic integration in Asia, and supports its advocacy for a Eurasian security system independent of the West. Through the SCO, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) can pursue its intertwined economic and security objectives in Central Asia within a cooperative multilateral structure that does not disrupt its other regional initiatives.

During the SCO’s early evolution, Russia was the most important contributor to its security activities. Russian contingents have subsequently participated in most SCO-related drills, and many other members’ armed forces employ Soviet/Russian military equipment. In the economic domain, Russia has made progress in encouraging SCO governments to use more non-Western financial instruments, which are less vulnerable to international sanctions. However, members have not yet established a separate SCO payment system or a Greater Eurasian Partnership.

Beijing has been the driving force behind the SCO’s evolution outside the security realm. PRC discourse emphasizes the congruence of Chinese-SCO values and takes pride in how the so-called Shanghai Spirit animates the organization. More concretely, China can use the SCO to advance its priority programs and challenge Western influence in Central Asia. The organization accomplishes this goal without overtly threatening Russian interests by characterizing its activities as SCO rather than PRC projects. In the defense domain, participating in SCO exercises gave the Chinese military some initial opportunities to rehearse power projection missions, though the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has since prioritized other geographic contingencies. The PRC has set forth an ambitious agenda for the SCO during its current chairmanship.

The Russian and Chinese governments have pursued conflicting policies regarding the SCO, especially concerning the organization’s economic policies and, more recently, proposed changes to its unanimous voting requirement. Nonetheless, they have successfully managed their divergences within the SCO and kept these differences from damaging their overall partnership. The organization’s enlarging membership will likely decrease its focus on Central Asia but make it a more effective tool for Moscow and Beijing to project influence elsewhere.

Hudson Institute has produced this paper for the study Russia-China Security Interactions in Central Asia: Bilateral and Multilateral Dimensions. This project analyzes the Sino-Russian relationship in Central Asia through three case studies. The first two papers assess Russian and Chinese ties with Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, which have the largest economies and populations in the region. The third paper evaluates Sino-Russian interactions with the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. A final paper draws on these three texts and other data to assess Russia’s and China’s overall relationships in Central Asia, project their future interactions in various scenarios, and evaluate the implications for the United States and its partners. Senior Fellow Richard Weitz is the primary author of the paper. Alexiya Mikerina, Marie Mach, Alexander Peris, and Ryan Wright provided research assistance. David Altman, Jack Feise, Mark Melton, Konstantin Shchelkunov, and Hannah Skaggs helped edit the text, while Ian Maready helped with the design. Hudson Institute would like to thank the Russia Strategic Initiative of the US European Command for funding this study.

This publication was funded by the Russia Strategic Initiative U.S. European Command. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Defense or the United States Government.

Introduction

This paper first reviews the history and structure of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. The following section analyzes Russia’s and China’s diplomatic, economic, and security goals regarding the organization. The paper then details how Moscow and Beijing pursue their regional agendas within the SCO framework. The final section assesses how Russia and China have managed their policy divergences concerning the SCO. It also projects how the organization’s evolution could impact the two countries’ influence in Central Asia and other regions.

|

Paper Roadmap

|

History and Structure

The SCO is a unique organization—neither a traditional mutual defense alliance nor a multinational economic institution. It is the world’s largest regional organization in terms of population, geography, and combined economic output. It also has a more comprehensive agenda than most regional organizations, encompassing security, economic, and social questions. Though it has a narrower geographic focus than some other groups, the SCO has become one of the most prominent non-Western institutions connecting Russia with the People’s Republic of China and other partners.

The organization’s original purpose was to regularize relations between China and the four newly independent countries that emerged along its western and northern borders following the Soviet Union’s abrupt dissolution (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and the Russian Federation). In 1996, these states began holding annual presidential summits within a so-called Shanghai Five format to discuss select regional issues. In 2001, the five governments established the SCO to institutionalize their interactions. Besides continuing the annual leadership summits, renamed as meetings of the SCO Heads of State Council, they began holding regular meetings of their foreign, defense, law enforcement, economic, and other national agencies. They also broadened the geographic scope of their interactions by including Uzbekistan, which does not border China. At their June 2002 summit in St. Petersburg, the SCO governments adopted a charter establishing the organization’s principles, objectives, agenda, and structure.1

The SCO pursues many security activities. Early on, its member governments adopted several confidence-building measures regulating military activities along their joint borders. Additionally, they hold recurring meetings among their defense ministers, armed forces chiefs, general staffs, and other security agencies. Some of these sessions occur on the sidelines of bilateral and multilateral interagency summits. Since 2003, the SCO has organized frequent antiterrorist exercises that have involved regular armed forces, law enforcement agencies, and border security personnel. These exercises serve multiple purposes, including developing contacts, improving proficiency, enhancing interoperability, and reassuring member governments.

Before the Russian military launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the members held large Peace Mission exercises approximately every two years. These drills involved large troop contingents from multiple countries. But the last exercise using that moniker occurred in 2021, at the Donguz training range in Russia’s Orenburg Oblast. Eight SCO members—China, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan—contributed approximately 4,000 military personnel to Peace Mission 2021, which simulated attacking terrorist targets.2

Interestingly, the August 2022 SCO Defense Ministerial stated that the members “decided to hold a joint military counter-terrorist command post exercise Peaceful Mission 2023 in the Russian Federation on responding to new tactics used by international terrorists.” The joint communiqué further observed that “Russia suggested that during this exercise, the interested parties focus on countering unmanned aerial vehicles, ensuring information security, and preventing terrorist attacks involving chemical and biological weapons.”3

Though several SCO members, notably China, participated in Russia’s annual strategic command post exercises in 2022 and 2024, the next major SCO exercise, Interaction-2024, did not occur until July 2024. According to the PRC media, this drill in China’s Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region “marks the first time the relevant agencies from all SCO member states have participated in a joint counter-terrorism live drill.”4 The military and law enforcement personnel from the 10 participating countries rehearsed employing helicopters, armored vehicles, robotic dogs, and aerial drones against terrorist groups.5

The Shanghai Convention on Combating Terrorism, Separatism, and Extremism, signed at the organization’s founding 2001 summit, commits the members to countering the three “evil forces” of international terrorism, ethno-separatism, and political “extremism.”6 The SCO subsequently institutionalized counterterrorist cooperation by creating a Regional Antiterrorism Structure (RATS) in Tashkent. Since its official opening in June 2004, the RATS has promoted studies of Eurasian terrorist movements, facilitated data sharing regarding terrorist threats, and exchanged advice on counterterrorism policies. It has also coordinated exercises among SCO security forces and organized efforts to disrupt terrorist financing.7

The 2022 Samarkand Summit Declaration reiterated long-standing calls to compile “a unified list of terrorist, separatist and extremist organizations whose activities are prohibited” by SCO members, suggesting the organization has not been able to realize this perennial goal.8 Following a decade of growing interest in cybersecurity, internet control software, and information-technology-enhanced surveillance, the RATS established “information security” as a priority work issue in 2023.9 It is currently facilitating the Program of Cooperation between the SCO Member States Against Terrorism, Separatism, and Extremism for 2025–2027.10-

SCO leaders consistently deny any intention of creating a Eurasian version of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Article IV of the SCO friendship and cooperation treaty, signed in August 2007, affirms that “the Contracting Parties shall not participate in alliances or organizations directed against other Contracting Parties and shall not support any actions hostile to other Contracting Parties.”11 The SCO has officially remained a security organization (i.e., one focused on combating transnational nonstate threats such as terrorism) rather than becoming a collective defense structure like NATO (i.e., one possessing capabilities for waging conventional wars against nonmember countries). Its activities promote confidence-building measures, strengthen border controls, and facilitate law enforcement and intelligence cooperation against transnational threats.

The SCO’s charter does not authorize collective defense operations, and the organization lacks dedicated military forces, an integrated command structure, or a combined planning staff. Any large multinational military operation that members participate in under SCO’s auspices would have to involve an ad hoc effort by their national militaries.

During the 2023–24 Kazakhstan presidency, the SCO held 150 events, made Belarus the tenth full member, and signed some 60 strategic documents encompassing primarily energy, economic, and counternarcotics issues. Due to the summit’s decision, the organization now has 10 full members, several formal observer states, and more than a dozen dialogue partners in the SCO Plus framework (see figure 1). The July 2024 Astana summit also launched a new SCO Investors Association to encourage direct and portfolio investment in member countries’ priority sectors.12 Kazakhstan President Kassym-Jomart Kemeluly Tokayev’s proposal for developing military confidence-building measures for combating terrorism, separatism, and extremism remains under consideration.13 The members also discussed establishing an SCO anti-drug center in Dushanbe.14

Figure 1. SCO Members and Dialogue Partners

Source: Adapted from Beth Warrington, “Shanghai Cooperation Organization Members and Dialogue Partners in 2023,” in Edward A. Lynch and Susanna Helms, “The Shanghai Cooperation Organization,” Military Review (January/February 2024), https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/English-Edition-Archives/January-February-2024/Shanghai.

Russian Goals

|

Moscow’s Objectives Regarding the SCO

|

The Russian government routinely promotes non-Western multinational structures, such as the SCO, as tools to disrupt the established international order. In July 2024, Russian President Vladimir Putin said the SCO had “firmly established itself as one of the key pillars of a fair, multipolar world order.”15 He advocated “creating a novel architecture in Eurasia of cooperation, indivisible security, and development . . . to replace the obsolete Eurocentric and Euro-Atlantic models that gave unilateral advantages only to individual states.”16 The previous month, Putin said Russia aimed to leverage the SCO and other regional institutions to build “a new system of bilateral and multilateral guarantees of collective security in Eurasia” that would work toward “phasing out the military presence of external powers in the Eurasian region.”17

The March 2023 Concept of the Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation advocates the same institutional integration in the economic realm. It envisages a Greater Eurasian Partnership that aggregates the “potential of all the states, regional organizations and Eurasian associations, based on the EAEU [Eurasian Economic Union], the SCO and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) as well as the conjunction of the EAEU development plans and the Chinese initiative ‘One Belt One Road’ [later renamed the Belt and Road Initiative, or BRI] while preserving the possibility for all the interested states and multilateral associations of the Eurasian continent to participate in this partnership and—as a result—establishment of a network of partner organizations in Eurasia.”18

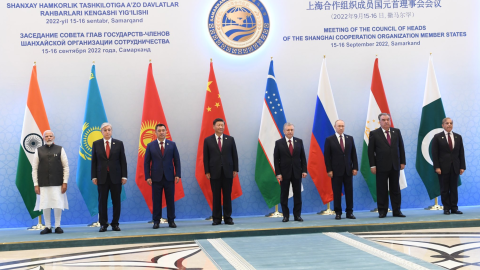

Participating in SCO activities allows the Russian government to demonstrate that it is not internationally isolated despite its aggression against Ukraine and its other abhorrent political-military policies. For example, Putin’s attendance at the 2022 SCO summit in Samarkand marked his first in-person foreign meeting with international leaders since Russia invaded Ukraine again in February 2022 (see figure 2). Though no other attending leaders backed Russia’s actions regarding Ukraine, none openly censored them either. Senior representatives of international organizations, including United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres in 2024, have also attended recent SCO summits with Putin.

Russian officials further perceive the SCO as a tool against regional terrorist threats, including as a means to influence other members’ counterterrorism policies. Central Asian nationals were involved in the most severe recent terrorist attack against Russia, the Crocus City Hall concert assault on March 22, 2024. The Islamic State—Khorasan Province (referred to as ISIS-K, ISKP, or IS-Khorasan) group based in Afghanistan orchestrated the attack. Russian officials have also praised the SCO’s contributions to countering narcotics trafficking.19

Chinese Goals

|

Beijing’s Objectives Regarding the SCO

|

For Beijing, the SCO is valuable for projecting economic and security influence in Central Asia without infringing on Russia’s traditional role as the region’s primary security provider. China can advance these goals directly through SCO-related measures. It can do so indirectly by leveraging the organization’s diplomatic and economic ties to induce other governments to pursue PRC-favored policies, such as suppressing anti-PRC messaging and embracing Beijing-backed economic initiatives.

In the security domain, the PRC can leverage the SCO to secure its western borders (which encompass Xinjiang, where the local Uyghur population is resisting Beijing’s assimilation policies). The organization also gives it a means to thwart international terrorist threats (especially from Afghanistan, an operations center for regional terrorist groups) and protect its extensive energy and other economic interests in other members from violent attacks.20PRC President Xi Jinping told the other SCO leaders in July 2024 that “security is a prerequisite for national development, and safety is the lifeline to happiness of the people. No matter how the international landscape changes, our Organization must hold the bottom line of common, comprehensive, cooperative and sustainable security.”21

China also wants the SCO to complement—or at least not impede—its other economic, security, and ideological foreign policy instruments. These have waxed and waned over the years but have most prominently included the BRI and, more recently, the Global Development Initiative, Global Security Initiative, and Global Civilization Initiative. The PRC has also launched a dedicated China–Central Asia mechanism with leadership summits and a permanent secretariat.22 The Xiangshan Forum, an annual defense and security conference that the PLA oversees, also regularly includes senior Central Asian and other SCO representatives.23

Despite the advent of these more recent instruments, Chinese support for the SCO remains strong. More than half of the approximately 10,000 attendees at the 2024 Astana summit were Chinese nationals.24 Xi has welcomed the organization’s recent expansion of ties beyond Eurasia, highlighting how the “SCO member states have friends across the world.”25

Figure 2. Leaders of SCO Member States at the September 2022 Summit in Samarkand

Source: Narendra Modi (@narendramodi), “With SCO leaders at the Summit in Samarkand.,” Twitter (now X), September 16, 2022, https://x.com/narendramodi/status/1570687339713929217.

Russian Means

|

Moscow’s tools of influence concerning the SCO

|

Russia has contributed critically to the SCO’s security activities throughout its evolution. Russian forces almost always participate in, and sometimes host, SCO-related drills. Many other members use military equipment of Russian or Soviet origin, and Russia is also important to the SCO’s counterterrorism efforts. According to Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, the Russian government has for several years advocated establishing a unified center, based on the RATS, to address narcotics trafficking, terrorist financing, and other organized crime that can exacerbate terrorist threats.26

Putin often praises the SCO’s contributions in his bilateral meetings with Central Asian leaders.27 Lavrov also regularly mentions its positive role to other member governments.28 Furthermore, Moscow leverages other countries’ interest in joining the organization. For instance, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan recently requested Putin’s support for his country’s membership aspirations.29

In his presentation to the 2024 SCO Astana summit, Putin advocated “creating a new Eurasian architecture of cooperation, indivisible security and development. . . . to replace the obsolete Europe-centric and Euro-Atlantic models that gave unilateral advantages only to individual states.”30 As noted, Russian diplomacy advocates this SCO-related restructuring in both the economic and security domains. According to Putin, the core components of the new Eurasian security system could include a partnership among the Union State of Belarus and Russia, the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), and the SCO.31 When Putin confirmed he would attend the China-hosted SCO leadership summit in September 2024, he affirmed that the organization “will make further efforts to interconnect the integration processes within the Eurasian Economic Union and China’s Belt and Road Initiative with a view to forming a greater Eurasian partnership in the future.”32

Some of Russia’s most important economic partners belong to the SCO. Moscow has sought to enhance mutual commercial ties by encouraging the use of non-Western financial instruments, which are less vulnerable to international sanctions. At the 2024 Astana summit, Putin welcomed the use of national currencies in 92 percent of Russia’s transactions with other members from January to April 2024.33This growth, though, is due to the initiative of individual member governments rather than collective efforts within the SCO, which presently lacks intergovernmental financial cooperation mechanisms. The Russian government has repeatedly, if unsuccessfully, proposed establishing a payment and settlement system within the SCO to surmount this impediment.34

Russia has also recently tried to polish its green energy credentials through the SCO. In April 2025, it hosted the first SCO Sustainable Development Forum in Omsk Oblast, where participating governments talked about decreasing their carbon emissions, adapting to climate change, and assessing regional and global sustainable development models.35

However, the Russian government has cultivated alternative Eurasian institutions as well. China and others have opposed adding an overtly military dimension to the SCO, to which the Russian government has responded by augmenting the CSTO. Unlike the SCO, the CSTO has become a genuine military alliance that can mobilize standing multinational forces against threats. Moscow has also promoted SCO ties with the CSTO and the CIS, which held a one-day joint counterterrorism exercise (Eurasia-Antiterror—2023) with the SCO in September 2023 (see figure 3).36

The EAEU has acquired roles that the SCO could have assumed if Sino-Russian disputes had not impeded it. Russian analysts note that, with Belarus’s recent elevation to full SCO membership, four of the five EAEU members (Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Belarus) belong to the SCO, while the fifth EAEU member, Armenia, is an SCO dialogue partner.37 The EAEU has also established a free trade agreement with SCO member Iran.38 More recently, Moscow has promoted development of the BRICS (a grouping that originally included Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), which includes many leading SCO countries but also important extra-Eurasian members such as Brazil and South Africa.

Chinese Means

|

Beijing’s Means of Influence Concerning the SCO

|

Beijing has been the driving force behind the SCO’s evolution. More established international organizations required the PRC to accept membership on a take-it-or-leave-it basis. However, Chinese officials have arguably driven the SCO’s design and evolution more than any other country—assuming the preferred role of rule-shaper rather than merely a rule-taker. Manifestations of China’s elevated role in the SCO are evident: Shanghai is in the organization’s name, and its headquarters are in Beijing. PRC writings and statements also emphasize the congruence of SCO and Chinese values and speak of a “Shanghai Spirit of mutual trust, mutual benefit, equality, consultation, respect for cultural diversity and pursuit of common development” as “a new driving force for equitable, just and reasonable international political, economic and security order . . . welcome from the outside world.”39As a vague concept, adherence to the Shanghai Spirit imposes few constraints on specific Chinese policies.

More concretely, China has found the SCO useful for advancing its programs and challenging Western influence in Central Asia without overtly threatening Russian interests there. Denouncing “the real threat of Cold War mentality” at the July 2024 SCO leadership summit, Xi called on member states to “consolidate the power of unity” to counter “external interference.”40Chinese leaders leverage SCO events to promote PRC initiatives regarding other members. For example, Minister of National Defense Dong Jun took advantage of a recent meeting of the SCO Council of Defense Ministers in Astana to engage with Kazakhstan’s defense establishment.41

According to one PRC source, “the Chinese military and police personnel had the first regular encounter with their foreign counterparts” through participation in SCO exercises.42 These drills still provide regular opportunities for the PRC to enhance its regional power projection capabilities, rehearsing “air-ground combat operations in foreign countries, undertaking a range of operations including long-distance mobilization, counterterrorism missions, stability maintenance operations, and conventional warfare.”43 The Chinese armed forces have also tested new technology, such as drones, in SCO drills.

The 2018 Agreement of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization Member States on Joint Military Exercises provides an international legal foundation for the PLA to deploy on other members’ territories for SCO drills.44 The PRC has leveraged the SCO to expand its professional military education (PME) outreach to Central Asian states, establishing a training institute for SCO officers in 2014.45 However, during the last decade, the SCO has arguably become less important to the PLA’s development. China’s military has increased its capabilities remarkably in recent years and has developed a robust defense partnership with Russia, conducting many more exercises with the Russian armed forces than with any other foreign military.

In the economic domain, the PRC’s aggregate trade with all SCO member states, observer states, and dialogue partners reached a record $890 billion in 2024, amounting to 14.4 percent of China’s total exports.46 The PRC has strived to embed the BRI within the SCO framework to overcome other countries’ concerns about its initiatives. By characterizing its activities as SCO rather than PRC projects, the Chinese government can decrease regional anxieties about them. Yet, thanks to its growing economic primacy in Eurasia, China can bypass the SCO whenever necessary and pursue essentially ad hoc bilateral deals that it couches in the terms of multilateral initiatives.

The SCO’s economic bodies have held numerous events. However, commercial deals attributable to their activities have been lacking.47 At the 2023 summit, Tokayev lamented that the SCO had not yet executed a major economic project under its auspices.48 A Kazakhstani journalist dismissed many of the documents SCO members adopted at the 2024 Astana summit as “aspirational.”49

Economic initiatives that Beijing has launched under the SCO’s auspices consist primarily of bilateral deals in which China provides loans, investments, and additional benefits to other members. At the July 2024 Council of Heads of State meeting, Xi said China will provide at least 1,000 training opportunities to SCO-affiliated countries and host some 1,000 youth exchanges relating to digital technology through 2029.50 Although Beijing takes care to frame these inducements within an SCO framework, the PRC most likely would have pursued these initiatives even if the SCO had not existed. Similarly, China’s economic ties with other SCO members would likely have increased even without the organization due to the proximity between resource-hungry China and its resource-rich Eurasian neighbors.

In mid-July 2024, China assumed the rotating annual SCO presidency for the first time in seven years. Though some analysts have questioned Beijing’s continuing interest in the organization, the PRC had adopted an ambitious action agenda for the year. Under the slogan “Upholding the Shanghai Spirit: SCO on the Move,” the PRC overtly seeks “deeper SCO cooperation in politics, security, trade, cultural and people-to-people exchange, and mechanism building, among other fields.”51 In the first three months of this year, China hosted meetings of the SCO border security leaders, the Council of the Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure, the SCO International Military Cooperation Organs, and an SCO counterterrorism exercise. Furthermore, the PRC Ministry of National Defense held the first SCO young and middle-aged officers’ exchange on October 20–30, 2024. More than 20 military officers and defense officials from SCO members, observer states, dialogue partners, and friendly countries attended.52

The PRC will end its term by hosting the Twenty-fifth Meeting of the Council of Heads of State of the SCO in the summer or early autumn in the northern city of Tianjin. By this time, the PRC chair aims to hold more than 100 meetings and events within the SCO framework, including some 40 “institutional” meetings, such as a Political Parties Forum, International Investment and Trade Expo, and Poverty Reduction and Sustainable Development Forum.53 The planned economic activities encompass all eight major areas of the PRC Global Development Initiative (climate change and green development, digital economy, connectivity, financing for development, food security, industrialization, poverty reduction, and public health).54 The PRC is driving the SCO’s political agenda regarding artificial intelligence (AI). In late May, the city of Tianjin hosted the 2025 China–Shanghai Cooperation Organization Artificial Intelligence Cooperation Forum, which “aims to strengthen practical collaboration in AI development and governance among SCO member states.”55 China is also still trying to establish an SCO Development Bank.56

In the security domain, the PRC has convened a RATS session, a meeting of border defense chiefs, and a counterterrorism exercise.57 It is also organizing activities to expand and improve counterterrorism cooperation within the RATS.58 In line with Russian proposals, China is transforming the RATS into a more integrated “universal center” for addressing the “three evil forces” of terrorism, separatism, and extremism.59 The two main written deliverables that members are likely to consider for approval at the heads of state summit will be a 10-year (2025–35) development strategy and a joint statement on the “80th anniversary of the victory of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and the World Anti-Fascist War” (i.e., the end of World War II).60

Figure 3. Eurasia-Antiterror—2023: Joint Anti-Terrorism Drill of the SCO and CIS

Source: “Joint Anti-Terrorism Drill of the SCO and CIS: Eurasia-Antiterror—2023,” SCO, September 22, 2023, http://eng.sectsco.org/20230922/-Joint-anti-terrorism-drill-of-the-SCO-and-CIS-Eurasia-Antiterror---2023-959008.html.

Russia-China Interactions and Implications

|

Sino-Russian SCO Exchanges and Effects

|

The SCO helps manage Sino-Russian interactions regarding Central Asia despite the two governments’ occasionally sharp disagreements regarding the organization’s development.The Russian government professes support for various Chinese economic initiatives in principle. However, in practice, it has exploited the organization’s unanimity rule to block PRC proposals to create an SCO-wide energy club, free trade zone, and robust development bank.61Russian-Chinese security differences have also circumscribed the SCO’s potential military role. For instance, the PRC blocked Russian efforts to strengthen ties between the SCO and the Moscow-led CSTO.62More recently, to overcome deadlocks and increase institutional efficiency, some PRC scholars have proposed relaxing the unanimity requirement and allowing a simple majority of members to reach some decisions. Russian representatives resolutely oppose waiving the unanimity rule.63

Other factors also weaken the SCO as a regional institution. A fundamental principle of the organization is respect for the principles of non-intervention and sovereignty, which exclude intervention in members’ internal security crises. When a terrorist incident occurs in a member country, the organization tends to merely issue statements of support for the attacked governments. Furthermore, “bilateral disputes are not subject to discussion within its institutions.”64 As a result, the SCO played no role in managing the recent fighting between members India and Pakistan, which could have ended in a nuclear war in the heart of Asia. Many accords that member countries adopt under SCO auspices consist primarily of bilateral deals; the organization merely provides a convenient negotiating venue and a multilateral gloss. Russian and Chinese government representatives, including Putin and Xi, have many other opportunities to meet outside the organization’s purview. The SCO, lacking substantial organic resources or authority, depends on its members’ sustained contributions. A resumption of Moscow and Beijing’s historical rivalry for Eurasia would doom the SCO to irrelevance.

Still, the SCO provides Russia and China with low-cost benefits. For example, the organization regularly adopts multinational declarations that align with Russian and Chinese goals. The July 2024 Astana Declaration embraced “the central coordinating role of the UN” and reiterated “that the unilateral and unrestrained build-up of global ballistic missile defense systems by individual countries or groups of states has a negative impact on international security and stability.”65 The Twenty-third Meeting of the Council of Heads of Government of Member States in October 2024 supported Russian and Chinese opposition to Western sanctions by denouncing “protectionist measures, unilateral sanctions and trade restrictions that undermine the multilateral trading system and hinder global sustainable development.”66

The SCO also provides Russia and China with a flexible multilateral framework to manage Central Asian issues.67 Despite recent membership expansion, Central Asia has always been the organization’s geographic focus. SCO summit declarations regularly affirm that members consider Central Asia the organization’s core region.68 A former SCO secretary-general maintained that “the SCO’s biggest security achievement in the last 20 years” was helping keep Central Asia stable despite all the region’s challenges.69 Earlier, the PRC perceived the SCO as a means to acquire influence in Central Asia without alarming Moscow, whereas Russia valued how the organization helped monitor and channel that expansion.Moscow and Beijing still benefit from the SCO as a source of mutual reassurance in which they overtly acknowledge one another’s interests regarding Central Asia. Moreover, Sino-Russian differences arguably reassure Central Asians by minimizing the potential for a China-Russia condominium within the SCO.

During the last few years, the Russian and Chinese governments have collaborated to enlarge the SCO’s agenda and, more recently, its membership beyond Eurasia.70 In 2023, the SCO elevated Iran from an observer nation to full membership, while in 2024, Belarus received a similar promotion. New so-called dialogue partners—a designation that can lead to eventual observer status or full membership—include more than a dozen countries: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Cambodia, Egypt, Kuwait, the Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sri Lanka, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates. Though not all the member governments are anti-Western, the organization has essentially become a bloc of non-Western countries with extensive ties to Russia and China. Moscow and Beijing can leverage the SCO as a “geopolitical showcase” of non-Western approaches to international issues.71 Western sanctions have made the Russian government more acquiescent to China’s economic and security ambitions for the SCO, while Sino-Western tensions have likely decreased Beijing’s resistance to the organization’s adoption of an overtly anti-US stance.72

Membership expansion can increase the SCO’s capabilities but also exacerbate disparities in geographic size, economic resources, demography, geopolitical orientation, and military power. The recent priority given to broadening over deepening the organization has complicated internal defense cooperation since the newest members lack the shared Soviet/Russian military legacy of the founding group. Though the SCO’s recent enlargement has diluted its cohesion and historic focus on Central Asia, the expansion has provided Moscow and Beijing with another means of currying favor with governments interested in joining the SCO and an augmented tool to project influence in Europe, the Middle East, and additional areas of Asia.73