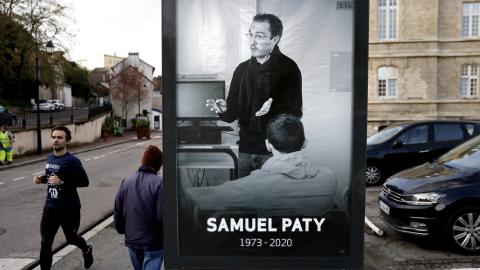

Much of France is focused on the trial of eight people stemming from the 2020 beheading of French schoolteacher Samuel Paty by Abdoullah Anzorov, an 18-year-old Muslim immigrant from Chechnya.

Anzorov himself is not on trial since he was shot dead by police minutes after his butchery. The focus now is on those who encouraged and enabled him. Seven men and one woman are appearing in Paris’ special criminal court. They include friends accused of helping buy weapons for the attack and spreading false information about Paty, which prosecutors argue contributed to a climate of hatred that led to the killing. This raises difficult questions about legal limits on speech, especially where religion is concerned.

There have been very much larger assaults by Islamist extremists in France, including repeated attacks on the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo and the 2015 Bataclan massacre, which claimed 130 lives.

But Paty's case has drawn special attention because it focused on a lone and gentle teacher falsely accused of blasphemy and beheaded a week later. French President Macron declared that he was killed because he “embodied the values of the French Republic.” There have been rallies across the country, and this past Oct. 14 there was a minute of silence to honor both him and Dominique Bernard, another teacher killed in similar circumstances. Several schools have been named in his honor and he has been awarded France's highest award for bravery, the Légion d'Honneur.

Paty was teaching a course in ethics in Conflans-Sainte-Honorine in the Paris suburbs, and one class concerned free speech. In that session, he showed cartoons from Charlie Hebdo that many Muslims regard as blasphemous, and for which many staff members had been murdered five years earlier. Unlike the magazine, he had no intention to shock. He cautioned the students beforehand and said that if they were uncomfortable seeing the caricatures, they need not stay in class or else they could simply look away.

One 13-year-old student had missed the class because she had been suspended from school for two days for repeated absence and rudeness. To hide her suspension from her father, she made up a garbled version of what she had heard had happened in Paty's class and said that he had insulted Islam.

Enraged, her father, Brahim Chnina, and his friend Abdelhakim Sefrioui went to the school the next day and demanded action against Paty. They also launched a vicious online campaign against him. The school received a deluge of threatening emails and phone calls and police were sent to protect it. A week later, Anzorov, enraged by the online claims and accusations, traveled from his home 100 kilometers (62 miles) away, followed Paty, beheaded him and then displayed his severed head on social media. Police later shot Anzorov as he advanced towards them, armed.

Others were charged and tried for varying levels of complicity in the murder. In 2023, Chnina's daughter was convicted for making false allegations and given an 18-month suspended sentence. Five other students at the school, ages 14 and 15 at the time, were found guilty of having helped point out Paty to Anzorov when he asked where the teacher was. They maintained that they never thought it would lead to his murder, but were found guilty of criminal conspiracy with intent to cause violence.

Those currently on trial are charged with having have helped or provoked Anzorov, and here questions of complicity, free speech and legal culpability become more complex.

Naim Boudaoud, 22, and Azim Epsirkhanov, 23, are charged with “complicity in terrorist murder,” punishable by life imprisonment, since they helped Anzorov buy a knife and a pellet gun, while Boudaoud also drove Anzorov to Paty’s school. Their lawyers maintain that this was not complicity in murder since the two insist that they did not know what Anzorov was planning to do.

Others face a possible 30-year sentence for what they have said and posted online. Two are accused of labeling Paty a "blasphemer" in online videos, involvement in a "criminal terrorist" group and complicity in "terrorist murder.” The prosecution argues that their spreading lies about the supposed blasphemy on social networks had the goal of “designating a target,” “provoking a feeling of hatred,” and "preparing the way" for the murder. Their lawyers responded that they had never called for Paty's death and they also did not know what Anzorov had in mind.

The U.S. has had similar disputes. When Gabby Giffords, Steve Scalise and particularly Donald Trump were shot, there were allegations that the shooters were responding to wild accusations made by political opponents. But these claims were usually partisan ploys rather than serious arguments, and in any case, America's robust free speech laws safeguard such wild speech.

However, there are statements that are given lesser or no protection by the First Amendment, and these include speech integral to other illegal conduct, incitement to imminent lawless action, or that is a personal threat, such as a death threat. The charges in the current French trial maintain that the accused engaged in precisely this type of speech so that they might face similar charges if they were in America, although they could call on a wider range of defenses.

France, and much of Europe, has far more stringent restrictions on speech than does the U.S., but it remains to be seen whether, even in the heated atmosphere surrounding a terrorist murder, calling someone a blasphemer will be seen as a criminal act.

Enjoyed this article? Subscribe to Hudson’s newsletters to stay up to date with our latest content.