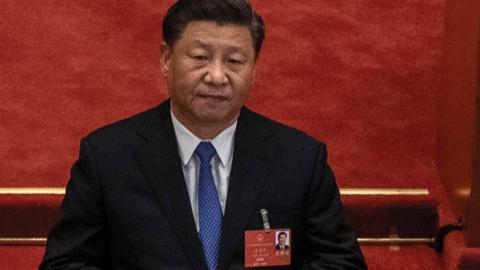

On May 22, China’s ruling Communist Party acted to end the autonomy that Hong Kong had enjoyed since its return to Chinese sovereignty in 1997. Hong Kong had been promised fifty years as a special, self-governing region inside the People’s Republic not just by Deng Xiaoping personally but by the provisions of the treaty that effectuated the city’s transfer from the UK to the PRC. To be sure, Beijing had been tightening its grip on Hong Kong and its governing institutions for years but, until last week, it never attacked it frontally. Why now?

Beijing’s move will not be cost-free. It will now have to be far more open in its use of force in suppressing millions of democracy-minded Hong Kongers. And then there are the economic costs. Hong Kong’s assets, real and financial, are owned in substantial part by state enterprises and well-connected mainlanders. Lower prices on the Hong Kong bourse and the dissolution of its rule of law will not only cost the already debilitated PRC economy, it will constrain, and maybe even destroy, Hong Kong’s capacity to be a vital source of international capital for the mainland.

But the main casualty will be the so-called “one country-two systems” scheme by which Beijing had hoped to lure Taiwan into its fold. From now on, no Taiwanese will ever be able to take seriously Beijing’s vows to protect their rights. Nor should the rest of the world. The treaty which enshrined Hong Kong’s special status was, in fact, deposited in the United Nations, and therefore is a matter for all UN members. The Chinese Communist Party’s unilateral abrogation of the treaty speaks to the credibility of any international commitment the Party has made or will make.

Deng Xiaoping’s epochal decision in 1978 to “open up and reform” China’s economy quickly led to a show of force throughout the Chinese-speaking world. Deng wanted the moribund People’s Republic to emulate the high-growth economies of Sinophone Asia—Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore. He also wanted to enlist the rich and successful Chinese communities in Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand. Billions of dollars in investments poured into the PRC from the other parts of Sinophone Asia, accompanied by the experience and expertise that overseas Chinese had acquired through long familiarity with capitalism’s ways. This was a behemoth in the making and the world-transforming potential of “Greater China” was sobering.

Why, then, didn’t the Communist Party not just sit back and wait for it to happen? In the 1990s, the affairs of Sinophone Asia were certainly moving in Beijing’s direction. In 1992, Taiwan and China had seemed to reach a so-called “consensus,” though no one anywhere was quite sure what “one China” meant. The reversion of Hong Kong in 1997 was widely welcomed, too.

It is alleged that Chinese strategic culture is uniquely endowed with patience, but Xi has been unwilling to play the long game. Xi has amassed unprecedented power on the claim that centralized and continuous Party leadership was needed to fulfill the “great rejuvenation” of the Chinese Nation. He has since sped-up the PRC’s many-faceted bid to establish a New Sinophone Order dominated by Beijing. As the intensifying “campaigns” and repression and mass atrocities inside today’s PRC empire show, the Party must “struggle”—Xi’s favorite word—against many powerful loci of opposition. Xi may believe he is realizing a “one China” on the Party’s own terms, but, instead, his actions have been driving the offshore components of Sinophone Asia away from the mainland.

On Taiwan, polling in February indicated that more than eighty percent of that island nation’s people think of themselves as Taiwanese, not Chinese. Beijing’s military build-up and incessant harassment of Taiwan have been met with more American security assistance and increases in Taipei’s own defense budget. Popular support for Taiwan throughout the world is also growing, inspired not only by Taiwan’s bravery in the face of the PRC, but also by the superb performance of its democratic system in the global health crisis that was exacerbated by China’s one-party dictatorship.

As for Hong Kong, millions there have turned out in pro-democracy demonstrations and a deeply-rooted sense of separate identity is surging. The young especially are defining themselves not as Chinese but as Hong Kongese, and there is widespread advocacy that they would be better off independent of the PRC all together.

All this is a reminder that “China” is not the same as the People’s Republic headquartered in Beijing and, indeed, that its political potentials are far greater than the Chinese Communist Party’s bid to dominate it. The most consequential, albeit often underappreciated, force in driving the modern history of Sinophone Asia, has been the interrelationship between its so-called “core” and its “periphery.” Indeed, since the late nineteenth century, if not earlier, the Sinophone core has drawn repeatedly on the many smaller polities of the periphery for ideas and energy. For one example, Sun Yat-sen’s advocacy of a Chinese Republic ultimately freed modern China from imperial control because of the strong support for it in the overseas polities and networks of Sinophone Asia. Likewise, Deng’s efforts to revivify the People’s Republic—and to save Communist Party rule—would not have been possible without the know-how and aid of Greater China.

Today, the Communist Party under Xi has resolved to reverse this modern dynamic and assert its own imperial writ. And this has created a profound dilemma: Because Beijing’s tyranny and aggression have transformed the periphery into a major obstacle to the PRC’s own grand ambitions, the Party leadership now believes that its own self-preservation depends on quashing that opposition. The Party knows that the existence of compelling counter-models to it along the Sinophone periphery are a danger to its hold on power inside the People’s Republic itself. It is an historic gamble: Xi’s ongoing bid to subjugate Sinophone Asia to communist rule is threatening the very Asian peace and economic potential which made China’s emergence since 1978 possible in the first place.