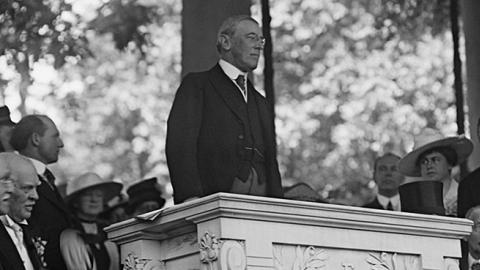

p(firstLetter). One hundred years ago, on November 30, 1917, the U.S. 42nd Infantry Division arrived in France led by their chief of staff, a young lieutenant colonel named Douglas MacArthur. Their arrival was proof that America’s entry into World War I would mark a turning point not only in that war, but in world history, with the emergence of the U.S. as a global superpower. Now a century later, we are coming to the end of that era — not as a global superpower, but as a superpower harnessed to the mission President Woodrow Wilson set for it at the time. When he called on Congress to declare war on Germany earlier that April, he laid out the goal: to make the world safe for democracy and fight the war that would end all wars. In his address to Congress, he said:

It is a fearful thing to lead this great powerful people to war, into the most terrible and disastrous of all wars, civilization itself seeming to be in the balance. But the right is more precious than peace, and we shall fight for the things which we have already carried nearest our hearts — for democracy, for the right of those who submit to authority to have a voice in their own government, for the rights and liberties of small nations, for a universal dominion of right by which a concert of free peoples as shall bring peace and safety to all nations and make the world itself at last free.

That was quite a burden for Americans to assume in 1917, but Wilson himself had no doubt that it was put there not by him, but by our own moral destiny. “We set this Nation up to make men free,” Wilson declared later. “And we did not confine our conception and purpose to America, and now we will make men free.” And every president since — from FDR and Truman to Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama — has had to grapple with the ghost of Woodrow Wilson and his legacy of high-minded idealism and universal mission.

That is, until now. With Donald Trump, we finally come to the end of Wilson’s legacy, for good or ill. A year after his election, it’s clear that Trump sees a very different mission for the United States and a very different way to use American power — to advance American interests, not humanity’s. From his perspective, and for the voters who elected him, Wilson’s ghost has too often led America on a path to disaster.

Of course, this isn’t denying that Wilson’s legacy has had its positive side. American intervention in World War I did prevent imperial Germany from dominating Europe; later, it saved the world from fascism in World War II and from Communism in the Cold War. Under George W. Bush it halted the steady advance of radical Islam after 9/11, and today it’s breaking the geopolitical threat posed by ISIS.

But by harnessing American power and interests to serve a morality based on abstractions such as “promoting democracy and human rights,” Wilson also set America on a course that led us to assume the burden of being “globocop.” The high ideals also became an excuse that American presidents sometimes used to restrain American power: In the name of a higher morality, they circumscribed American might when its full exercise could have eased the global burden that from time to time has torn the country apart.

Wilson himself was the first to make that mistake in 1918, when he unilaterally agreed to an armistice with a Germany that was on the verge of military collapse. It would take another world war, from 1939 to 1945, and millions of deaths before Germany’s dream of dominion over Europe was finally broken. That same year, in 1918, Wilson also put the brakes on the Allied intervention in the Russian civil war, thereby saving Vladimir Lenin’s renegade Bolshevik regime from certain destruction. The result was a century of at least 65 million deaths at the hands of Communist regimes around the world and a 50-year standoff with the Soviet Union in the Cold War.

Truman exercised the same restraint in Korea, where he and his advisers rejected the warning of General Douglas MacArthur, after hard experience in World Wars I and II, that there was “no substitute for victory.” Instead, Truman accepted a stalemate at the 38th parallel with a Communist North Korea, which went on to develop nuclear weapons, now aimed at the United States.

Lyndon Johnson made the same mistake in Vietnam. There, JFK’s Wilsonian pledge to “pay any price, bear any burden” to defend liberty around the world plunged us into a war that proved unwinnable under rules of engagement that, instead of showing America in a bright moral light, destroyed the cultural fabric that held the country together and ended in ignominious defeat — and the killing fields of Cambodia.

In their different ways, Trump’s immediate predecessors repeated the same pattern of high-minded goals and disastrous results. George W. Bush thought he could turn America’s war against radical Islam into a great crusade for democracy. “The policy of the United States,” he stated in his Second Inaugural, “is to seek and support the growth of democratic movements and institutions in every nation and culture, with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny in our world.” Wilson himself might have written this sentence. Barack Obama hoped America could set a new moral example for the rest of the world by “leading from behind” in military conflicts and by treating climate change as a greater threat than ISIS.

Both proved failures with American voters, and both weakened America’s position in the world. Now Donald Trump has turned his back on that high-minded Wilsonian tradition. He understands it wasn’t American idealism that saved the world in World War II and during the Cold War, but American military and economic strength. To Trump, America is not a great cause, but a great power that must compete with other great powers to safeguard its most vital interests.

His thinking is actually much closer to that of Teddy Roosevelt, who, in addition to his famous advice to speak softly and carry a big stick, also said, “a milk-and-water righteousness unbacked by force is to the full as wicked as and even more mischievous than force divorced from righteousness.” Indeed, when TR added that “nothing would more promote iniquity . . . than for the free and enlightened peoples . . . deliberately to render themselves powerless while leaving every despotism and barbarism armed,” he might have been talking about North Korea and ISIS. And he might’ve been stating a position that Trump would wholeheartedly endorse.

So we come to the end of one era of American foreign policy, based on idealism and grand visions, and the opening of another based on advancing national interests together with a strong dash of realpolitik. Exorcizing Wilson’s ghost won’t be easy. It won’t make liberal humanitarians or neoconservatives very happy. But it could mean the start of a new “American century,” one in which the United States can stand as a strong confident symbol of freedom, rather than as freedom’s instrument for saving the world from itself.