The United Nations Security Council recently heard firsthand testimony from the victims of a chemical-weapons attack in Syria. A Syrian doctor spoke of his frantic efforts to treat more than 100 people who were hit by chlorine-filled bombs in the town of Sarmeen. Many were vomiting and suffering respiratory distress.

These kinds of attacks are becoming more common and will increasingly be a component of 21st-century warfare. America’s enemies are clearly equipped to carry them out. Terrorist groups such as al-Qaida and the Islamic State have said they intend to acquire biological and chemical weapons — and use them against America.

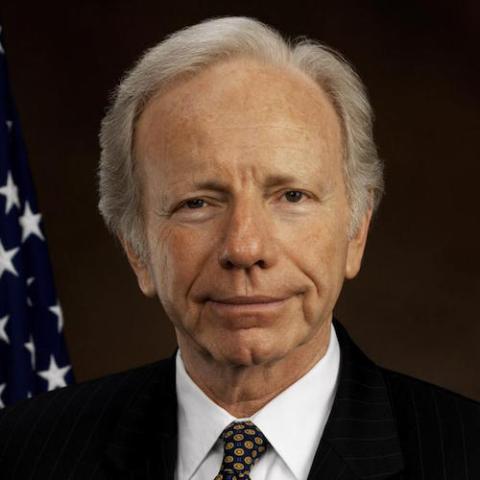

Unfortunately, our nation is dangerously unprepared to prevent or respond to such attacks. Whether the actor is another country, a terrorist organization or even Mother Nature, the consequences are potentially catastrophic. That is why we agreed to become co-chairmen of a new panel on biodefense, hosted by Hudson Institute and Inter-University Center for Terrorism Studies, whose members include former Secretary of Health and Human Services Donna Shalala, former Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle, former Rep. Jim Greenwood and former Homeland Security Adviser Kenneth Wainstein.

Congress and the president must devote more attention to the threats posed by biological and chemical agents — formulating and executing a coherent and comprehensive plan to protect the American people from them now.

For evidence of our national unpreparedness, look no further than the Ebola crisis last year. We knew that a disease like Ebola could reach our shores. We knew it was coming. Even so, when it did, no one seemed to know who was in charge or exactly how to respond.

Screening procedures were not in place at airports. Hospitals lacked the proper guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for donning gowns and gloves. Health care professionals contracted the disease because they didn’t know exactly how to protect themselves.

And there were precious few prototype vaccines and therapeutics for the illness; they’d been ignored since the early stages of their development.

The Ebola outbreak spread because we and the rest of the world did not manage the disease properly. Imagine if America’s enemies had deliberately released a similarly deadly infectious agent within our borders.

It’s as if our government has forgotten what it learned from the anthrax attacks in 2001 — which targeted Daschle’s office, among several locations. Since then, the government has spent approximately $10 billion annually on biodefense. But the United States still isn’t adequately prepared to protect its citizens from a major biological or chemical event.

Our political leaders have not made biodefense a national security, economic or health care priority.

Consider the recent decline in funding for biological and chemical readiness efforts. After peaking in the mid-2000s, grants for homeland security and public health activities related to biodefense and infectious disease preparedness have fallen precipitously.

As Julie Gerberding, former director of the CDC, explained before our blue ribbon panel, the drop-off in funding wasn’t “because any one individual decided it wasn’t important, but because we allowed competing priorities to interfere and to attenuate what had been off to a good start.”

Our political leaders must make funding for biodefense a priority before a biological or chemical attack — not after one has already occurred. And they must make sure the money is spent efficiently and effectively.

But funding alone is insufficient. The federal government must also install and maintain a workable leadership structure that allows for rapid, effective decision-making as soon as we find out about a biological or chemical threat, whether we are alerted by intelligence, biosurveillance, or because an attack or outbreak has occurred.

According to several veterans of the administrations of Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush who presented before our panel, our biodefense efforts have become far too Balkanized, with authority and responsibilities dispersed among too many cabinet agencies and across all levels of government.

Congress and the president can address these shortcomings by institutionalizing biodefense at the White House, naming and empowering an individual with the ability to coordinate the efforts of the intelligence, defense, diplomatic, agricultural, public health, health care, scientific, law-enforcement and emergency-response communities to deal with biodefense. For this to be effective, that official needs budgetary authority to ensure his or her orders are executed. Nobody wants another ineffectual czar.

Biological and chemical threats are among the most sinister — and potentially catastrophic — our nation faces. It is only a matter of time before our enemies take advantage of our vulnerabilities in biodefense and attack us. That’s why our political leaders must give these current threats the attention they deserve and do what it takes to defend the American people from them.