This article was originally published in Italian under the title “Il vicolo cieco della Belt & Road” in Aspenia 98 “Trappole cinesi,” Aspen Institute Italia, October 2022, www.aspeninstitute.it.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a signature program of Xi Jinping, has had undoubted success in supporting Xi’s ambitions to reestablish China as a global leader while strengthening its mercantilist economy. Nonetheless, developed and developing countries are reconsidering the program because of its success—largely for China itself—and because of the global economic and political crises since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. BRI also has increasingly visible problems caused by its operating structure, prompting participants and developed countries whose geoeconomic and geopolitical interests are undermined by the program’s expansion to reassess it. Continued BRI growth is at best questionable and probably unlikely in the wake of growing pushback to the program as well as growing problems inside China itself.

Historical Context

In his ongoing quest to position himself in the pantheon of legendary Chinese rulers from its long history, Xi Jinping frequently invokes his comprehensive BRI as the latest example of a long line of explorers and emperors expanding trade to the West, starting with the Han Dynasty in 140 BCE. Pride of place is given in his speeches to the early fifteenth-century maritime adventurer Zheng He, whose massive fleets blazed a southern ocean trail to Africa in a way that the twenty-first-century maritime silk road now mirrors. These parallels elide the reality that the old silk road reached its heights in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries in the Eurasian empire of the Mongolian hordes, which ruled China and territories across the steppes to ancient Rus for well over a century. The Ming rulers famously forced Zheng He to withdraw from his expansionary quest after reaching eastern Africa. This return to a static Middle Kingdom extended for more than four centuries, including what Xi now calls China’s “century of humiliation” when its territorial integrity was compromised. Indeed, much of Chinese history reflects a pattern of long periods of inward-looking, self-satisfied focus on its East Asian landmass interspersed with relatively brief episodes of territorial expansion.

After the disastrous autarchic period of Mao Zedong’s early communist dynasty, Deng Xiaoping put China back on a path of more openness to the outside world and pursued more global trade, investment, and diplomatic measures designed to strengthen its economy. His operating philosophy in the world however was not aggressive, borrowing Sun Tzu’s maxim of “Hide your strength, bide your time.” Xi’s BRI built on the brilliant success of Deng’s turn to a more market-oriented and globalized economy. Xi however has been much more ambitious than Deng in wanting to establish China as a dominant global economic and political power to rival and even surpass the United States. Deng did insist on maintaining the supremacy of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) while tolerating and even encouraging private enterprise. In contrast, Xi has gradually weakened some of the most successful private firms while reasserting the primacy of the CCP and the state apparatus in the economy.

Goals of BRI

BRI is an integral part of Xi’s more aggressive ambitions—both economic and political. Its economic importance is paramount. Building on the mercantilist, manufacturing-based model that evolved under Deng and his successors, the expansion from the Chinese center via efficient transportation and other infrastructure by land, air, and sea facilitates the export of manufactured goods and related services from Chinese producers, which is the initiative’s first goal. BRI networks also help attract foreign producers in search of access to its growing middle-class markets in China. Furthermore, foreign direct investment into the Middle Kingdom attracts global expertise to build up domestic industries. China has been able to bolster its ambitions to become a high-technology powerhouse in part by attracting investment and forcing technology transfers to its own firms. Expanding transportation networks helps China to facilitate the recycling of foreign currencies—especially dollars—which it uses to fund infrastructure development through BRI.

The second goal is to gain access to the raw materials and agricultural commodities needed to build its modern economy and for which China lacks adequate indigenous capacity. Energy projects dominate almost half of BRI investments in resource-rich countries, especially in Africa, Latin America, and South and Mideast Asia. Mining and agriculture are also targets for BRI projects that both ease access to production in underdeveloped countries and allow Chinese firms to control operations in major projects. Perhaps the greatest success of BRI has been in securing access to raw minerals and dominating the processing of minerals such as rare earths, cobalt, and lithium. China has also built some 30 percent excess refining capacity for crude oil to take advantage of privileged access to below-market-priced supplies from BRI partners in Russia, Iran, and Venezuela.

Third, China uses BRI to build political support for its increasingly ambitious efforts to become a dominant global actor and gradually undermine the influence of the US and its allies. China’s “wolf warrior” diplomats have had some success in urging BRI beneficiaries to side with its international priorities. The most recent examples are the UN votes to condemn China’s ally Russia for its invasion of Ukraine and to open a debate about abusive practices in Xinjiang province. Many Latin American, African, and South Asian BRI beneficiaries declined to join the United States and European Union for these votes. Hungary, the most important EU recipient of BRI investment, blocked the EU’s support for allowing Taiwan to gain observer status at the World Health Organization.

Finally, the maritime vector of the new silk road provides the fast-growing Chinese military means of projecting power across the South China Sea, Indian Ocean, and Persian Gulf and into Africa. The network of ports along these routes—not only in the Sri Lankan port of Hambantota, which China formally controls after the Sri Lankans defaulted on the Chinese debt used to build it—can be used as ports of call for the Chinese navy. China built a military port in Djibouti in 2017, and China attempted to hide the building of an exclusively military facility at Khalifa port in the United Arab Emirates. But construction was halted after Western intelligence discovered it. Meanwhile, China, Russia, and Iran conducted joint naval exercises near the Persian Gulf earlier this year to prepare for protecting Mideast oil exports to China in times of sanctions.

Both the land and sea lanes of BRI are part and parcel of the way Xi and the Chinese military think about the “dual use” of the overall BRI project.

Trade Success and Debt-Trap Problems with BRI

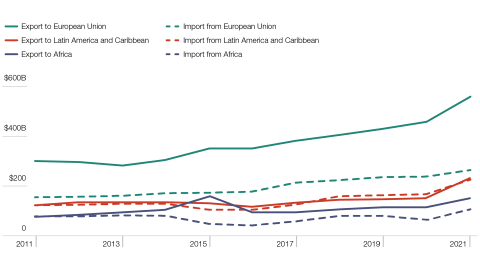

The BRI has certainly been a large part of the Chinese ability to penetrate foreign markets and gain access to needed raw materials. Figure 1 shows the evolution of trade—largely in goods—with three of the most important destinations for BRI investments.

Figure 1: China’s Export and Imports with Europe, Africa, and Latin America and the Caribbean, 2011–21

Around 1,000 trainloads of cargo now cross the Asian steppes into Europe each month. The new silk road contributed to the near doubling (85 percent) of Chinese exports to the EU area since 2011 and a near doubling of China’s trade surplus with the manufacturing-dominated EU. European investment in China is a major component of these results as important German and other EU firms have established hundreds of factories in the Middle Kingdom for both sales in China and exports to the EU and the rest of the world.

As figure 1 shows, China has also increased trade with Africa since 2011 (exports grew by 103 percent and imports by 44 percent) and Latin America (exports grew by 90 percent and imports by 88 percent) since the inception of BRI. It maintains a sizable, $40–50 billion annual merchandise trade surplus with Africa and near balance with Latin America. The latter is a large source of raw materials such as minerals, agricultural products, and energy for China.

One recent study1 of seven emerging market BRI participants found a correlation between BRI growth and a deterioration in the bilateral trade balance of these countries between 2013 and 2021. Kenya’s trade deficit with China grew 106 percent in this period; Pakistan’s by 164 percent, Sri Lanka’s by 41 percent, and Kyrgyzstan’s by 47 percent. Even with energy-exporting Angola, the deficit grew by 34 percent after BRI helped develop the energy potential of that sub-Saharan country.

The Exploitative Structure of Chinese Foreign Assistance and Development Programs

The principal reason for China’s trade success in BRI, in addition to the fundamentally mercantilist nature of its economic model, is the way China structures its projects and its overall financial assistance program. China is now by far the world's largest supplier of official foreign assistance. In contrast to traditional Western and Pacific Rim assistance patterns, which feature a mixture of grants and below-market-rate loans, and to World Bank assistance, which also structures aid with favorable loan rates, repayment terms, and outright grants, China’s aid is in large part structured around loans at or around market rates and repayment terms that are generally of short- to medium-term duration. Chinese credits are also frequently collateralized, and repayment is tied to returns from specific projects. Thirty percent of Chinese credit deals require escrow accounts controlled by the lender.

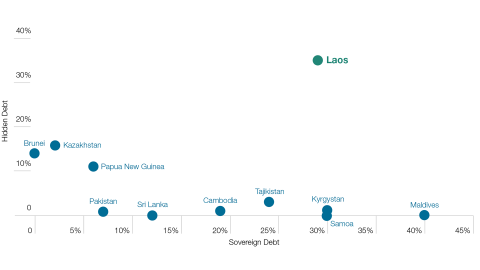

China’s approach also differs from Western-style aid in how BRI responds to debt crises in recipient countries. Especially since the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing economic slowdown, development loans in emerging markets have come under considerable stress. One study estimates that 60 percent of low-income countries are now at risk of debt distress, and the World Bank suggests the level of debt accumulation and stress is at the highest level in 50 years. Forty-two emerging market economies now have debts to Chinese lenders (both sovereign debt and bank or other commercial debt) exceeding 10 percent of GDP. These numbers do not account for the “hidden debt” in which China specializes and does not report. One study estimates that such debt is half again as large as more visible debt totals. Figure 2 shows estimates of both sovereign debt and “hidden” debt for selected Asian and Pacific partners of China.

Figure 2: Combined Hidden and Sovereign Debt Exposure to China for Selected Countries

Note: Selected countries’ debts as percentage of GDP, 2000–17 data. Hidden debts are defined as those without explicit sovereign repayment guarantees, but that could become government obligations in the future

Most developed Western countries and their major commercial bank lenders belong to the Paris Club and adhere to its—often lenient and favorable to desperate borrowers—rules for debt restructuring in crisis situations. China largely rejects Paris Club-type debt relief. Seventy-five percent of Chinese sovereign credit contracts have a “no Paris Club” clause that prohibits participation in “collective restructuring” and immunizes China from offering comparable patterns of restructuring and outright debt forgiveness agreed by the Paris Club for individual borrowers. Instead, China frequently responds to distress by offering short-term suspensions of repayments, loan extensions, and partial refinancing as a last resort. Often, as famously seen in Sri Lanka, defaults result in the Chinese takeover of income from defaulting projects or outright seizure of the underlying assets.

Compounding the problems with the structure of loans, unlike Western or World Bank–supported projects, China frequently insists on using its own construction or operating firms, and its own labor, to execute projects. This undermines the value to recipient countries of the projects supported by China. Often, the quality of the Chinese project work is suspect or inept. A recent example is a $3 billion hydroelectric project in Ecuador that is barely able to function because of the failure of parts supplied by the Chinese equipment supplier that cannot readily be repaired. China also regularly uses BRI to support domestic firms like Huawei, which is now the leading provider of telecommunications equipment to much of the developing world.

For many BRI projects, the basic economics are simply unsustainable. Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port project and a trade center in Colombo were never likely to generate the sort of returns needed to repay Chinese loans. The results in that country were disastrous economically and politically.

A final problematic element of China’s BRI is that it frequently brings corruption in its wake. The most systematic database for foreign aid, AidData at William and Mary University, estimates that 35 percent of Chinese BRI-related infrastructure projects are beset by corruption, labor abuses, environmental degradation, and public opposition.2 A curious example is that of the interrelated road, port, and oil development projects in Angola. Two top aides to former President Dos Santos of Angola have been indicted for participating in the diversion of some $1.5 billion in project money and oil-related income for personal gain. But a testimonial from the now-deceased Dos Santos absolves the aides of misconduct and places the blame squarely on himself, at least for charges related to the China International Fund!3

In summary, the total investment in BRI of at least $838 billion since 2013 has resulted in growing Chinese trade surpluses and ability to acquire needed commodities and energy, but also in major problems in recipient countries. In 2020 and 2021, $52 billion of its loans had to be restructured, and at least $118 billion have been restructured since 2001. Even further problems and potential financial crises appear likely in the years ahead as the global economy weakens.

Pushback to BRI and Its Future

The accumulation of issues related to the structure and operation of BRI projects—and the impact of contemporary events such as the economic slowdown in China and in the West; Xi’s forceful and uncompromising repression of human rights in Tibet, Xinjiang, and Hong Kong; its overreaction to Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan; and its support of of Russian aggression in Ukraine—have resulted in greater pushback against Chinese mercantilism and BRI. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz this year expressed frustration with BRI and warned of a looming financial crisis: “There is a really serious danger that the next major debt crisis in the global south will stem from loans that China has granted worldwide.”

In a broad geopolitical context, Chinese mercantilism, its interference in domestic politics such as its sanctions on Lithuania or convincing Hungary or Greece to block EU political decisions, and its support of Russia’s brutal expansionist war have strengthened US, European, and Pacific Rim determination to contest and confront expansionist Chinese programs. Hopes for the work of the new US-EU Trade and Technology Council symbolize the new spirit of Western cooperation on policy toward China.

The June 2022 G-7 meeting gave a boost to US-led efforts, starting with the Trump administration and continuing with the Biden team, to counter Chinese economic influence. Participants coalesced around the inaptly named “Build Back Better World” initiative to coordinate allied efforts to offer an alternative to China’s BRI and general foreign assistance programs. Yet mustering the financial resources and creating a realistic cooperative model of joint project development and management remain a challenge, especially at a time when there is a strong possibility of a recession and countering the Russian war of aggression in Eastern Europe creates difficult political problems for allies opposing that aggression.

In China too the impetus for expanding BRI has weakened. China has depleted around 25 percent of its foreign exchange reserves (which is an even bigger decline as a percentage of its growing GDP) and faces a burgeoning domestic economic challenge due to the real estate crisis, the impact of COVID-19 lockdowns, a possible recession, and trade sanctions against Chinese firms from its two largest trade partners. Since the outset of the pandemic-induced global slowdown, the number of China’s billion-dollar BRI investments has not exceeded 10 annually, far below the 57 BRI loans of that magnitude reached in 2015.

Even if China can overcome its economic crisis, it will likely not reach the pre-COVID-19 levels of BRI investment due to the growing global pushback on its methods and highly inefficient and corrupting results. The US, EU, and Pacific Rim allies could help ensure this result if they succeed in creating and funding a more effective foreign assistance program, as conceptualized at the Alpine G-7 meeting, and focus global attention on the abusive and exploitative methods employed in the BRI.

The author acknowledges the research assistance of Abby Fu.