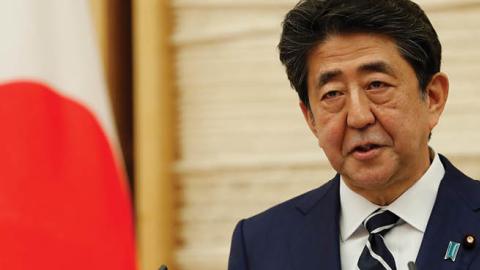

My personal memories of Shinzo Abe, who was just assassinated, center on meetings at his office to discuss U.S.–Japan relations, and his gracious conversation with me when he spoke at the dedication of the new Hudson Institute building on Pennsylvania Avenue in 2016. The close relationship between Abe and Hudson really got under way after his first disastrous sally as prime minister in 2006–7, when everyone in Japan thought his political career was over. But my colleagues Ken Weinstein and Lewis Libby kept the relationship going through Abe’s Wilderness Years, until his triumphant return to office in 2012 — a display of loyalty, and the belief that he represented the future of Japanese politics, that earned his loyalty and trust in return.

I was in many ways the beneficiary of that trust, with the keen interest he took in my work on defense trade cooperation between the U.S. and Japan. Because Abe understood that what I called the “special relationship” between the U.S. and Japan — a term that pleased him — closely paralleled the more famous one between the U.S. and the U.K. Except in Japan’s case, this was a historic alliance not built on a common language or shared cultural heritage, but on a shared strategic vision of the role both countries needed to play in promoting democracy as well as security across the Indo-Pacific region, especially in the face of a growing threat to both from China.

This is the other facet of Abe I came to appreciate, as Japan’s most profound strategic thinker — a thinker on the par of Churchill or Bismarck. It was Abe, in fact, who became the driving force behind the most important democratic coalition in Asia today, the so-called Quad, made up of Japan, the U.S., India, and Australia.

Then-candidate Shinzo Abe first proposed an “Arc of Freedom and Prosperity” in his 2006 campaign. He envisioned it as a network of states stretching across the Eurasian continent, brought together by their commitment to freedom and the rule of law. He narrowed that vision during his brief initial spell as prime minister to the four nations who make up the Quad today. His “Confluence of the Two Seas” speech was an extraordinary moment in Japanese politics: a Japanese premier stepping up to present a new way of thinking about a common strategy for a region that was normally seen as two distinct regions, one centered on South Asia and the Indian Ocean and the other made up of nations perched along the shores of the Pacific.

When Abe returned to office in 2012, he immediately set forth this vision again, in a speech titled “Asia’s Democratic Security Diamond.” “I envisage a strategy whereby Australia, India, Japan, and the U.S. state of Hawaii form a diamond to safeguard the maritime commons,” he said in the speech. This diamond would stretch from the Indian Ocean to the eastern Pacific, a de facto alliance in which “Japan, as one of the oldest sea-faring democracies in Asia, should play a greater role in preserving the common good in both regions.”

But Abe also understood that this effort meant confronting China’s increasingly aggressive strategy in both oceans, including the militarization of the South China Sea and the threats to Japan’s own national sovereignty in the East China Sea. Despite rhetoric about a “pivot to the Pacific,” the Obama administration remained lukewarm to Abe’s efforts to see the growing threat from China as one that the U.S. and Japan needed to confront together, while rallying the other regional democracies to help. Abe’s Quad vision was put on ice by an indifferent American president.

However, Abe’s tireless efforts paid off with Obama’s successor, President Trump. The new way of seeing Asia culminated in the resumption of the Quad dialogue in Manila in November 2017, where the idea of a “free and open Indo-Pacific” and a “rule-based system” for regional governance became common coin.

But unlike some advocates of “rules-based” systems, Abe understood that the idea of regional security was meaningless without the threat of military force. More than any other post-war Japanese prime minister, Abe was responsible for breaking Japan out of the quasi-pacifist stance it had assumed since 1945. He insisted that Japan had to increasingly shoulder its share of the defense burden with the United States, and that this had to be reflected in Japan’s defense budget.

Of all Abe’s legacies for his own country, this may be the most important. He saw a growing defense budget (it reached an all-time post-war high during Abe’s last year in office) as a sign not only of national health, but also of Japan’s commitment to helping to contain the growing threat from China and the long-standing ballistic-missile threat from North Korea.

This is why the effort by the liberal media to portray Abe as an “ultra-nationalist” has it exactly backwards. He understood that a strong and assertive Japan was an essential part of the fabric of peace and security in Asia, and a key to preserving a liberal international order in the face of China’s ambition to overthrow that order.

Shinzo Abe will be missed, not only as a friend to Hudson Institute and to America, but as the master visionary of a free and open Indo-Pacific based on the power and influence of the Quad. The tragedy of his death will only be compounded if that vision is allowed to fade or atrophy in the face of the challenges to that freedom still to come.

Read in National Review