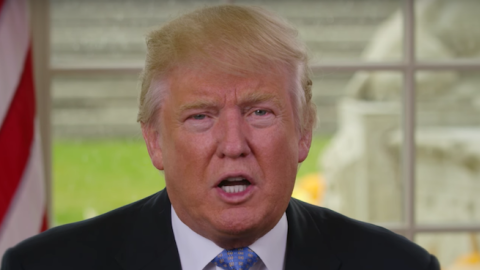

That's the easy part. President-elect Donald Trump went on YouTube to announce two of his goals. The first was to show the print and television moguls who have been coming and going from Trump Tower in an effort to work out a modus vivendi with the president-elect that he doesn't need them to get his message through to the American people. The more important one was to announce that on day one of his administration he would file a "notification of intent to withdraw" from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a step in removing the cornerstones from the Obama Legacy edifice. Since that partnership lacks the necessary Senate ratification and has never been in operation, Trump is withdrawing from something that in effect does not exist. Easy.

Unfortunately, our negotiator-in-chief to be ignored one of the rules followed by all good negotiators: Anticipate what your partners and adversaries will do. Which was, in the case of our eleven TPP partners, notably including traditional ally Australia, to scurry for the shelter of China's 16-member Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, which excludes America. The result is that America's influence in the region has declined further, and China's influence has soared. Trump saw TPP as a trade deal, when in reality it was an attempt to have America, rather than China, set the rules of trade in the Pacific region—the world's fastest growing one. And because TPP members Peru and Chile will now join the Chinese group, China gets the bonus of extending its influence throughout Latin America, an area America has considered in its sphere of influence ever since 1823, when President Monroe issued his famous Doctrine, in effect warning other nations to stay out of Latin America.

Now to the hard parts. Trump plans to negotiate 11 separate bilateral trade deals with the former members of TPP. But the nations sitting across the table have the alternative of signing on with a resurgent China rather than with a retreating America, which Trump has said will pull back from abroad in order to rebuild the United States as he "makes America great again."

Next in line for Trump's attention is the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which he says is the worst trade deal America ever signed and which he plans to renegotiate or "terminate". He can indeed "terminate" the trade pact simply by providing Mexico and Canada with six months' notice; congressional approval is not required. Mexican imports have devastated auto industry companies in the Midwest, including Indiana, Vice President-elect Mike Pence's home state.

Provocation enough for Trump, who knows that Mexico counts on America for $4 out of every $5 it earns from overseas trade. But our southern neighbor has a few weapons should Trump make good on his threat to impose stiff tariffs on stuff made in Mexico.

* In 2000, America's unions persuaded the government to require trucks bearing goods from Mexico to offload them at the border and reload them onto U.S. trucks driven by union members, in contravention of the NAFTA agreement. In 2009, after much wrangling, Mexico responded with duties as high as 20 percent on 89 agricultural products, including apples, for which Mexico is a key market. Congressional representatives from affected states quickly demanded and got a reversal of the trucking fiasco.

* The U.S. price of a Ford Fusion would rise to $30,000 from $22,000 if Trumpian-level tariffs were imposed, and;

* Mexico could demand hard-to-get proof of origin before accepting deported felons.

Mexico says it will agree to "update" the 23-year old agreement, but not to tariffs or other barriers to its exports to the United States. The fudge factory will have to work overtime to draft an agreement in these circumstances. And it will. Doubt that and consider this episode.

During the campaign, Trump threatened to impose a 35% tariff on small cars to be manufactured in a plant Ford was building in Mexico to accommodate a planned move of production from a plant in Indiana. One month later, after his election victory, Trump announced victory: Ford chairman Bill Ford called to tell him a plant would not be moving to Mexico. "Just got a call from my friend Bill Ford, who advised me that he will be keeping the Lincoln plant in Kentucky - no Mexico … I owed it to the great state of Kentucky for their confidence in me," tweeted a faux triumphant president-elect.

Never mind that the stay-in-America plant was one that produced SUVs and Lincolns in Kentucky, and was never slated for closure. Or that construction of the $1.6-billion small-car facility in San Luis Potosi, Mexico, creating 2,800 good jobs for Mexicans, proceeds apace.

China represents a bigger target. The U.S. trade deficit with China, which already holds $1.2 trillion of our IOUs, hit a record last year and is rising. Until forced to staunch currency flight by keeping the value of the yuan from plunging, China manipulated its currency to keep its value and the price of its exports low. It subsidizes producers who "dump" goods on world markets. It steals intellectual property and forces American companies to turn over technology in return for market access. It requires state-owned enterprises to buy from Chinese suppliers.

China needs America's markets, which should give Trump an important card to play. But Chinese president Xi Jinping is not without weapons. On his visit to the United States last year, he placed an order for 300 aircraft worth $38 billion. Boeing employs about 160,000 American workers and wants its share of China's future market, projected to hit 6,810 planes and be worth $1 trillion over the next 20 years. (Whether Boeing will get those orders depends on how quickly its agreement to build a plant in China makes that country self-sufficient and even an international competitor.) Apple has important manufacturing facilities in China. And China's purchases of soy beans from the farms that make up Trump country total over $10 billion annually.

Some within the Trump camp are urging him to adopt a policy of targeted retaliation rather than start a general trade war. He could:

* increase the number of dumping cases brought to the World Trade Organization when Chinese manufacturers sell in the United States below some measure of cost, or with the benefit of subsidies;

* impose targeted duties, as George W. Bush did on steel and Obama on Chinese tires;

* impose sanctions on companies that steal intellectual property;

* allow an eager China to pour billions into U.S. infrastructure projects, and then tweet that he is making them pay for past sins.

Trump might also try to redeem his pledge to the displaced American workers who are the collateral damage of globalization, and whose votes put him in the White House, by helping them rather than by harming consumers and export-oriented firms. An effective program of support for laid-off workers, well-financed by transferring some of the gains of the winners of globalization, including investment bankers and consumers, to innocent losers would do just that. If one can be devised that overcomes the ineffectiveness of past such efforts.

This won't satisfy those of Trump's hardliners who see our trade deficit with China as the source of funds for the regime's expansion of its military. "We will have only ourselves to blame when the bullets and missiles begin to fly," writes University of California economist and Trump adviser Peter Navarro. If that view prevails, the world trading system is in for a shock.