The Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the new US National Security Strategy (NSS) highlight a resurgence of realpolitik.

The dim state of China-United States relations served as a backdrop to President Xi Jinping’s latest power consolidation. Heading into the CPC conclave, the general secretary urged party cadres to grasp “the historical position”, focus on “strategic tasks” and face problems with a “fighting spirit”.

From beginning to end, the meeting stressed themes of challenge and response. The opening report warned of “black swans”, “grey rhinos” and “dangerous storms”. Mr. Xi’s closing remarks promised “miracles that will amaze the world”, provided the faithful summon “the courage to fight and the mettle to win”.

But fight who and win how? These actions remain inscrutable, much like the mystery that shrouds former Chinese leader Hu Jintao’s unceremonious removal from the Great Hall of the People.

Bestowed a third term as party chief and packing the Politburo Standing Committee with loyalists, Mr. Xi remains Central Military Commission chairman and state president. The paramount leader boasts the authority to do what it takes to achieve China’s dream of national rejuvenation.

Will an all-powerful Mr. Xi run the table on neighbours? Will he solidify an international alliance of aggrieved partners—from Russia and North Korea to Iran, Pakistan and Myanmar—to keep the US occupied across multiple fronts? The party congress heightened anxiety throughout the Indo-Pacific region and beyond.

Beijing appears to be trying to offset the reassurance deficit.

China’s beleaguered property sector can no longer account for a quarter of the country’s growth. Market analysts fear what The Economist’s David Rennie calls a “communist monarch”—an authoritarian leader who places ideological rectitude and political control above an ongoing growth strategy for the world’s second largest economy.

Neighbours are looking for true partnership, not incremental accretions of Chinese sovereignty.

ASEAN envoys should query State Councilor Wang Yi’s Sino-centric take on the congress. Nodding to “ASEAN centrality” and a “shared destiny”, Mr. Wang alluded to an exclusive “Asian moment” before emphasising party unity with Mr. Xi at its core, and Xi Jinping Thought steering a modernisation strategy that “befits China’s national conditions” and expectations.

Americans reading the social media feed of Ambassador Qin Gang may have been similarly baffled over what to make of his Twitter post: “New Journey. New Era. New Missions”. If everything is new, how much continuity should we expect from China? After all, the party report derided “hegemonism and power politics”, presumably code words for the US.

Before the Twentieth Party Congress, “liv(ing) with each other in peace” and “cooperative rivalry” were plausible Chinese and American concepts for curbing great-power confrontation. Now, even the Biden administration’s original tripartite approach to China —“competitive when it should be, collaborative when it can be and adversarial when it must be”—seems quaint and anachronistic.

China’s party politics have left an after-party hangover.

Cure for the after-party hangover?

But analysts should take a deep breath before forecasting a year of US-China confrontation. Perhaps China’s economic headwinds will prompt Mr. Xi to seek a breather on intentional clashes. His cumulative power also does not make a hot war inevitable. Instead, the lingering effects of the party conference militate for an old type of international relations: power politics.

Some would say power politics never left us. At the University of Chicago, Professor John Mearsheimer has long argued that Democratic and Republican administrations succumbed to a “fantasy” about “liberalism’s inevitable triumph and the obsolescence of great-power conflict”.

Harvard University’s Professor Graham Allison also finds fault with the Washington establishment’s inability to understand the global power shift. Not only has the US Indo-Pacific Command been forced to “retreat from a strategy based on primacy and dominance to one of deterrence”, but if “there is a ‘limited war’ over Taiwan or along China’s periphery, the United States would likely lose”.

Without subscribing to Prof. Mearsheimer and Prof. Allison’s stark judgments, their sharp points should remind everyone that Americans can judge the US severely, not just China.

Consider the array of experts pouncing on the revelation that the US Air Force was permanently withdrawing two active-duty F-15 squadrons from Okinawa.

There are compelling reasons for making such a force posture change, primarily related to survivability, resilience and distributed firepower; rotating more advanced fighters such as F-35s and F-22s can provide greater lethality and a less predictable target.

But the poorly messaged move risks sending the wrong message to Beijing when the US secretary of state repeatedly warns of Mr. Xi’s accelerated timeline for Taiwan’s unification with the mainland.

The dispute only underscores the critical importance of China’s and America’s respective approaches to Taiwan.

A decisive decade

Two years after his election, US President Joe Biden released a series of authoritative strategy and defence documents. The White House sees this as a decisive decade of geopolitical competition akin to the 1940s. Decisions about China and other crucial challenges will shape international security for the rest of the century.

Although Russia’s February invasion of Ukraine can account for the delay and some revisions to the administration’s guiding vision, China remains in the cross hairs of an integrated US strategy.

“The People’s Republic of China (PRC) is the only competitor with the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military and technological power to do it,” asserts the NSS.

The public document is more circumspect regarding flashpoints, consigning the fate of Taiwan’s future to a brief recitation of past policy milestones.

Mr. Biden wants to reassure Taiwan that aggression against it will trigger a US response, and he wants to reassure Beijing that Washington still adheres to the “one China” policy that acknowledges Taiwan as part of China. As China’s power grows, the more Mr. Xi wants Taiwan merged under CPC management; as China threatens to subjugate Taiwan, the closer the US moves to prevent a violent change to the status quo.

Meanwhile, power grabs threaten to upend the Biden administration’s agenda for a free and open Indo-Pacific region.

In Europe, America is embroiled in a prolonged effort to deny rewarding Russian belligerence in neighbouring Ukraine. The Middle East remains fraught, and Washington might use military force to prevent Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons. In Asia, North Korea’s expanding nuclear capability and frenzied missile campaign complicate the search for stability and nuclear nonproliferation.

But the China challenge remains in a category of its own. The Nuclear Posture Review declares there “is no scenario in which the Kim regime could employ nuclear weapons and survive”.

But regarding a peer competitor like China, America’s overriding defence goal is more modest, to “dissuade the PRC from considering aggression as a viable means of advancing goals that threaten US vital interests”.

The US aims to confine the China challenge to the grey zone, the murky area short of outright force and across all domains and instruments of power. Taiwan thus tests the salient question regarding whether pragmatism between leaders operating in increasingly nationalistic domestic political arenas can avert escalation.

Domestic hardening

A further hurdle to salvaging great-power stability is the hardening of domestic politics. Power politics will continue to sell better than pragmatism in China and the US.

As China’s growth rate slows and debt, real estate and demographic crises deepen, the mix of ideology and nationalism at the twentieth congress is likely to be magnified in the country.

Historically, US foreign policy boasts a long tradition of pragmatism and support for global free trade. But today’s American body politic is roiled by division and anger, sometimes united only in a shared desire to block perceived predators.

Trading with a liberalising, resurgent China in the 1990s and 2000s was one thing. It is another to enable a repressive, confrontational regime seen as undermining the rules-based system Washington helped to build. It is little wonder that more than four in five Americans hold an unfavourable view of the government in Beijing.

China’s actions have driven Democrats and Republicans together to adopt sharp trade, technology and Taiwan policies. Earlier this year, former top Asia adviser Jeffrey Bader castigated the Biden administration for its confrontational “Trump lite” approach to China, reflecting how US-China policy has moved to the right.

As Mr. Xi begins his second decade at the apex of power in China, the latest party congress establishes the high expectation for asserting the CPC narrative around the globe.

The elevation of chief ideologist Wang Huning, the author of an influential Chinese critique of American capitalism and democracy, suggests we should expect no letup in Beijing’s pursuit of discourse power.

Testing pragmatism

Leaders have agency. Both Mr. Xi and Mr. Biden reached the pinnacle of power in their country because they were realists.

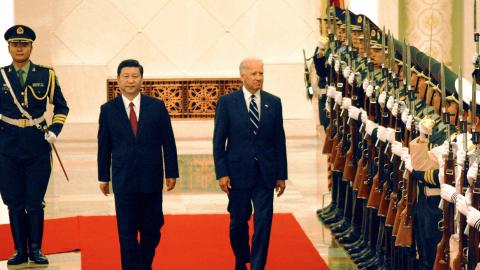

Meeting on the margins of the Group of 20 summit hosted by Indonesia in Bali in mid-November, the American president and the CPC general secretary could test the appetite for putting a floor beneath China-US relations.

Climate change is a vital long-term interest for both countries. But Russia’s and North Korea’s threats to resort to nuclear weapons strike at even more urgent, overlapping great-power interests. Further, they also show the need for US-China crisis management mechanisms.

The global economy also provides impetus to search for common ground, even if coordinating interest rates. Clarifying the rules of some high-tech decoupling and energy may be asking too much, but they are issues where a modicum of cooperation could be reassuring.

While there may never be an ideal time for great-power diplomacy, the need for it is undeniable. Mr. Xi and Mr. Biden can compete over narrative, technology and rules, but they must do so without turning a burgeoning cold war into a hot war.