Although Secretary of State Anthony Blinken’s mission to Beijing succeeded in rekindling high-level talks with China, stability between the world’s two most consequential powers will remain elusive.

Optimists can applaud that U.S.-China engagement is back on the 2023 calendar. The second half of the year will be cleared for Foreign Minister Qin Gang to visit Washington, presumably followed by a steady stream of senior official visits to China and culminating in a leaders’ meeting.

Secretary of Treasury Janet Yellen wants to curb U.S. investments that help modernize the People’s Liberation Army while avoiding decoupling and expanding cooperation. Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo wants to clarify tech export policies aimed at de-risking, while protecting U.S. firms in China and preserving U.S. exports to China valued at more than $150 billion a year. Climate envoy John Kerry wants to urge the world’s two largest greenhouse gas emitters to step up their efforts to tackle the global challenge of climate change. In November, a year after their first in-person leaders’ summit in Bali, a second meeting between Joe Biden and Xi Jinping will likely be held in San Francisco.

Pessimists can point out that stark disagreements remain. There are no signs that bilateral relations will be able to emerge from the deep trough into which the two powers have sunk. Even Secretary Blinken remains “clear-eyed” about the fundamental differences separating the United States and China — from Taiwan to technology and human rights to maritime rights. So, no one should be surprised if there are more disruptions to the diplomatic schedule. After all, relations have been treading water since a Chinese spy balloon fell into the ocean off the coast of South Carolina in February.

From further revelations about espionage and cyber intrusions that could stymie critical infrastructure in a crisis to sharp power threats against U.S. forces and our allies and partners, there is no shortage of likely problems ahead.

We often hear that U.S.-China relations have reached new depths. Military guardrails would be mutually beneficial, but apparently, that is not Beijing’s current view. Thus, the current aim of diplomacy is to ensure relations don’t sink even lower.

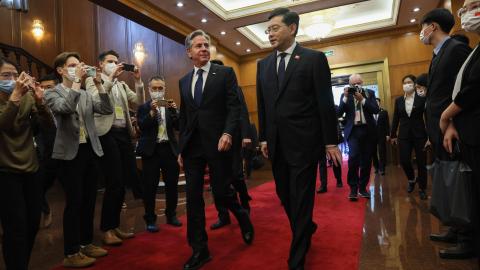

Shorn of pomp and sentiment, diplomacy is about sustained dialogue. China put Blinken through the wringer: fly from Washington to Beijing and then hold your own with Foreign Minister Qin for more than seven hours; on the next day, engage China’s top diplomat, Wang Yi, for more than three hours; and, finally, after the Chinese have milked Blinken of every word he might wish to utter to Xi, be granted 35 minutes with the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

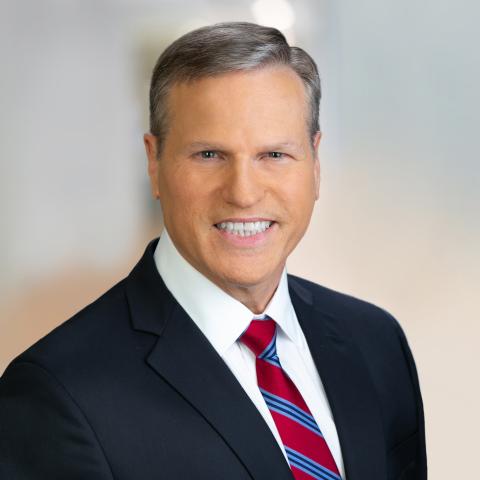

Blinken emerged from this exercise in diplomatic endurance with no visible signs of wear and tear. Still, spending your entire weekend jet-lagged, trying to inject your talking points while listening to a lengthy recitation of CCP watchwords about the need to show greater respect, stop interfering in China’s internal affairs, and cease denying China’s right to develop, is an under-appreciated skillset of U.S. foreign policy.

We should recall the last visit to Beijing by a U.S. secretary of state when diplomatic niceties were scarce. Then Foreign Minister Wang Yi accused the United States of a “direct attack” on trust, casting a shadow on bilateral relations, and demanded the Trump administration “stop this kind of mistaken action.” Secretary Mike Pompeo deflected the criticism, noting America’s “fundamental disagreement” with Beijing’s assessment.

Interspersed among the hours of Secretary Blinken’s tireless dialogue in Beijing, Qin repeated China’s call on the United States to change its mistaken approach, Wang admonished that Washington must choose either cooperation or confrontation, and Xi averred that “Neither side should try to shape the other side by its own will, still less deprive the other side of its legitimate right to development.”

Sustained diplomacy requires persistence, despite the absence of significant tangible results. Sometimes the reward of U.S.-China engagement, to invoke the poetry of T.S. Eliot, is to end a long exploration by arriving where you started and knowing the place for the first time. Secretary Blinken and his many hosts in China discovered nothing new from a frantic weekend of diplomacy. However, they did return the world to the glimmer of hope from Bali that great-power war is not inevitable.

The United States and China will cooperate when it serves their interests. Meanwhile, before bemoaning diplomacy as feckless or the abysmal state of U.S.-China relations, we should remember there is always a lower state to which major powers could return: namely, war. We should be thankful for the depths to which our diplomats will go to avert it.