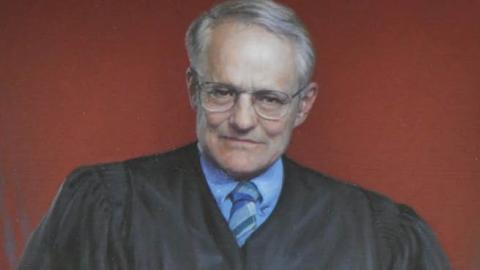

__These remarks were delivered at an event entitled “A Remembrance of Judge Stephen F. Williams” held by the Antonin Scalia Law School at George Mason University on October 9, 2020.__

Late in his career as a legal scholar and judge, Stephen F. Williams took a deep dive into Russian political history. He learned the language, so he could approach the subject with his customary particularity. He wrote two stupendous books, published in 2006 and 2017, on the doomed efforts of liberal reformers in the 12 years before the Bolshevik revolution of 1917.

Was this yet another of Steve’s exuberant hobbies, like city biking and pets and plant-based cuisine? When a man of his preternatural talents is suddenly snatched away, his friends want to remember him as a regular fellow like ourselves. And Steve’s casual demeanor and devotion to friendship encouraged us to think of him in this way. We all pick up new interests, and many of us became absorbed in the drama of Russian reform in the 1990s, following the Communist collapse. Steve, like other judges, signed up for exchanges with Russian jurists and gave talks there on the rule of law. He attended sessions with Russian reformers at the American Enterprise Institute. When he launched his first Russia book with a lecture at AEI, Steve’s discussant was the great Russian economist, Yegor Gaidar, who had recently spearheaded market reforms as Finance Minister, Vice-Premier, and Acting Prime Minister.

But the Williams Russia Period was not a detour. Steve’s books, whatever their initial motivations, spoke to America as well as to Russia. They were part and parcel of his vocations as a scholar of liberty and a judge overseeing the U.S. administrative state.

That first book, Liberal Reform in an Illiberal Regime, assesses Prime Minister Petr Stolypin’s agrarian reforms of 1906–1911, which permitted peasants to own and consolidate farmland that had been controlled by local communes. His theme is the problematics of well-meaning reforms handed down from on high in the face of stubborn local traditions. You first notice that Steve’s evaluations read like his judicial opinions—balanced, meticulous, persuasively judged. Then you realize that the author himself is a Stolypin in a robe. Today’s administrative state is an illiberal regime, based on non-representative lawmaking, non-independent adjudication, and impatience with private rights, embedded in a multitude of stubborn agency cultures. Appellate courts are of course much more constrained than Stolypin, who launched his reforms with an outright ukaz. But they are our guardians of constitutionalism and individual rights, insisting on fidelity to the Constitution and representative legislation as the cases and materials permit. Judge Williams’s calling was to open up springs of liberal reform in local regulatory communes and hope for the best.

Steve’s book does not even hint at that analogy, but sometimes it is too good to miss. Before the Stolypin reforms, the communes allocated property in small, ungainly, noncontiguous plots; discouraged transfers among peasants and assembly of larger tracts with natural scale economies; and periodically redistributed some of the plots. That is eerily similar to how the Federal Communications Commission manages the electromagnetic spectrum in 2020—our farmland. Alas, beyond the writ of judges, awaiting an American Stolypin.

Steve’s commitment to private property and competitive markets was not doctrinal or ideological, but rather empirical and humane. He wanted a system where, to a significant extent, “people are able to match their talents and interests with real work.” But he also saw property and markets as essential to liberal democracy, where human energies are deflected from accumulating and flattering power to producing goods and services of value to others. That larger project was the subject of his second book, The Reformer: How One Liberal Fought to Preempt the Russian Revolution.

Vasily Maklakov, a trial lawyer and riveting orator, was a leader of the left-liberal Constitutional Democrats—the Kadets—in the Russian Duma during the fateful years leading to the 1917 revolution. Steve presents Maklakov as a solitary voice for moderation, civil deliberation, and compromise. Russia was an atomized, zero-sum society, without mediating institutions to filter and guide popular opinions and passions. Politics was sheer personal positioning, where policy questions were judged wholly on who was for them and who was opposed. Not only the revolutionaries but the democratic reformers were fixated on the promise of majoritarian state power. Maklakov, virtually alone among the reformers, saw that this was a formula for the suppression of intellectual dissent, of Jews and other minorities, of property owners, of entrepreneurship. What Russia needed was not power but the rule of law and the habits of mind to support it. In Steve’s pièce de résistance, Maklakov pleads that everyone consider the strengths in their opponents’ arguments and the weaknesses in their own. For this he was scorned by the leaders of his own party.

It is impossible to read Steve’s stirring account without a tear for what was to come in Russia—and another tear for what has come in America. Now our politics is dominated by the quest for executive power, policy is subordinate to personality, moderation is scorned, and minorities and dissenters are selectively isolated and restricted. The difference is that we had robust traditions of democratic engagement and compromise but permitted them to atrophy. Let us hope that it is easier to recover lost Maklakovian habits than it is to build them from scratch.

I believe that Steve’s warm bonhomie and collegiality were more than personal charm. They were invitations—gateways into the serious questions of law, politics, and economics that were his life’s work, and illustrations of some of the answers he had found.

Read in Law & Liberty