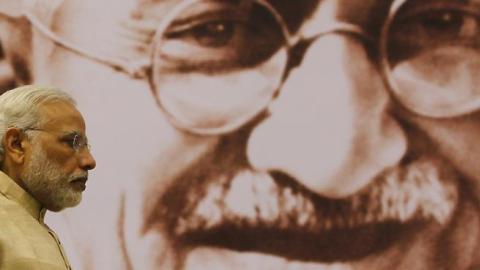

Prime Minister Narendra Modi appears to have pitched his legacy on an aggressive foreign policy but will that help him in the key arena of public opinion: building India's economy. In his first year as Prime Minister Mr Modi has traveled to 18 countries. He has visited both neighboring countries (Nepal, Bhutan, Sri Lanka and Myanmar) as well as countries far away (United States, China, South Korea, Brazil, Japan, Australia, France, Germany and Canada). His trips have focused on economic as well as strategic discussions and a strong pitch to the Indian diaspora in all those countries. While these trips have energized India's ties with these countries, the real benefits will incur only if India's economy continues to grow.

India's first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru (1947-64), argued that till the time that India is strong economically she will not be able to play a role in the world. India was able to punch above her weight during the 1950s-60s but that was primarily because of Nehru's focus on moral principles and championing decolonization. Despite having strong Prime Ministers like Indira Gandhi (1966-77, 1980-84), and playing a dominating role in the subcontinent, India remained an emerging power for decades.

Liberalization and the growth in economic power from the 1990s provided New Delhi with the resources to build India's military strength as well as be seen as a potential strategic partner by other countries. Indian strategists and policy makers often assert India has the right to be considered a great power purely on grounds of her civilizational heritage and population. Soft power matters but it is hard power (economic and military) that is critical to the promotion and expansion of soft power.

Mr Modi's election campaign and his appeal to a vast majority of Indians came from the belief that he was someone who understood that the path to the global high table lay through economic growth. Not only Indian corporates but those around the globe welcomed an Indian leader who was supposed to have a business sense. The Indian diaspora around the world too welcomed his rise to power as an Indian leader who valued them and would seek their help in building the country of their origin. Finally, the average voter looked forward to an India where he would be free from the proverbial Indian red tape or innumerable laws and regulations.

One year after the elections the only group which appears satisfied is the Indian diaspora. Every country Mr Modi has visited, it is the diaspora which is out on the streets, at the airports and embassies greeting and welcoming him with song and dance. They have been wooed, asked to invest in India and have also been promised ease of travel through life long visas. The corporate sector and the average voter are still waiting for when Mr Modi's government will deliver to them.

Providing a lifelong visa to the diaspora was much easier than changing bureaucratic rules. Similarly going on foreign trips and focusing on foreign policy helps divert attention away from what is happening at home. Yes, it is important to focus on foreign countries, especially those countries (Japan, China, the US, South Korea, the European Union) from whom India needs investment in key arenas like infrastructure and energy. However, foreign trips are what every prime minister does and Indian leaders have been well known to travel a lot. What is required is not just visiting other countries, promising or obtaining promises on investment but instead following up on previous promises to make sure that things move ahead. India adopted a 'Look East' policy in the mid-1990s; it has only now adopted an 'Act East' policy. A quarter of a century is too long a time for a country that looks upon itself as a future great power.

Mr Modi has invited investment from corporates in every capital around the world, from New York, Ottawa, Seoul, Canberra, Shanghai and Tokyo. These corporates are eager to invest but they do not see a welcoming environment. Even Indian corporates are hesitant to invest for fear of what some analysts have referred to as 'tax terrorism.' The previous Indian government left a legacy of retrospective taxation and during the election campaigns Mr Modi referred to this policy as a 'breach of faith' and promised to rectify it.

However, after coming in to power instead of changing the policy the current government has sought to find more ways to tax both corporates as well as individuals. Instead of setting up a system, like in the United States, where more people are included in the tax system, the government is creating a system where people once again fear the tax inspector. Instead of less government and more governance, there appears to be more government and confused governance.

India's economy has tremendous potential and there is a huge demographic divided which is waiting to be harnessed. Mr Modi's administration has a once-in-a lifetime opportunity to build on this by harnessing the Indian and global corporate sectors to spur Indian economic growth. However, this will require as much dedication to the domestic economy as he is investing in foreign policy.