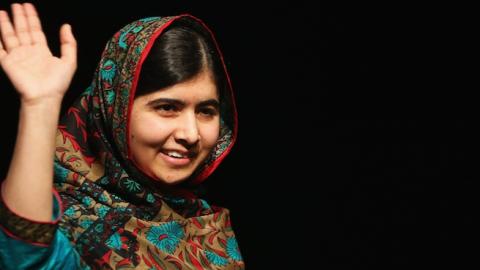

A 17-year-old from Pakistan has become the youngest person ever to win the Nobel Peace Prize—awarded Friday to Malala Yousafzai, for her courage in standing against the obscurantist Taliban and demanding her right to modern education. For this, she was shot in the head in 2012 by Islamist militants.

Malala, as she is known in Pakistan, shares this year’s prize with Indian children’s-rights activist Kailash Satyarthi. There is great symbolism in a young Pakistani and an Indian children’s advocate sharing the world’s most coveted award for promoting peace and human rights, at a time when the armies of the two countries are shooting at each other across their contested frontier in Kashmir.

While Malala’s courage in defying the Taliban’s barbarism won her the admiration of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, her Pakistani detractors’ criticism reflects the national malaise that young Malala has committed herself to fight. Hundreds of young Pakistanis, most of them supporters of cricket icon Imran Khan, have started the #MalalaDrama hashtag on Twitter to describe Malala as a tool of the evil West who is seeking to impose Western values on Islamic Pakistan. A few on Twitter even called for her to be charged with blasphemy, the catch-all accusation frequently used in Pakistan against those advocating anything but the most primitive ideas. Luckily, she now lives in Birmingham, England, after having come to Britain for medical treatment for her head wound.

Malala began documenting life under the Taliban in 2009, after they took control in the Swat Valley of northwestern Pakistan and then tried to shut down her school. The Taliban and their Islamist supporters oppose education for girls, and their concept of education for boys is far from enlightened. A young village girl with little outside exposure, Malala wished to connect to the rest of the world. She says she was inspired by the Pakistani Benazir Bhutto, who became the Muslim world’s first woman prime minister and was killed in 2007 by terrorists for challenging their ideas.

By rejecting the Taliban’s version of Islam—which was being brutally imposed by force of arms—Malala showed greater foresight than many of Pakistan’s politicians, generals and public intellectuals who have gradually ceded space to extremist Islamists. She didn’t buy into the propaganda description of the Taliban as a nationalist reaction to U.S. dominance or Indian influence, recognizing them as a menace that would set the country back several centuries.

Pakistan’s leaders have been in a deep state of denial about their national priorities for a long time. Religious extremism and terrorism are often not seen as a serious threat for a nation that has, since its inception in 1947, focused on acquiring military parity with its much larger neighbor, India. Instead of seeing the Taliban as murderous brutes fighting modernity, Pakistan’s strategic planners have considered them as allies against Indian influence in Afghanistan after the withdrawal of the Soviet Union.

Terrorist groups with an ideological affinity for the Taliban were assisted by successive Pakistani governments in hopes of resolving Pakistan’s long-standing dispute with India over Kashmir. Although Pakistan has lost thousands of its own citizens and soldiers to terrorist attacks since 9/11, strategic delusions continue to prevail.

Anti-Western sentiment and a sense of collective victimhood also have been nurtured as a substitute for serious debate on social or economic policy. The country’s resources have been devoted to maintaining a large military and expanding its nuclear arsenal, with inadequate investment in education, health care and other social needs. The result is that Pakistan appears on virtually every list or directory of countries that are facing the potential of state failure. Half of the country’s almost 200 million people remain illiterate, population growth remains high, and economic growth has risen only in periods of an increased flow of aid from the U.S.

Nothing illustrates the crisis of Pakistan, and possibly a large part of the Muslim world, better than a 2013 book by Mujahid Kamran, the vice chancellor of Punjab University, Pakistan’s largest institution of higher learning. In “9/11 & The New World Order,” Mr. Kamran—who has a Ph.D. in physics from Edinburgh University—claims that the 9/11 terror attacks were an inside job and that al Qaeda was a CIA asset. According to a September 2013 article in Karachi’s Express Tribune newspaper, Mr. Kamran told the audience at a book-launch ceremony that “the U.S. and British governments are controlled by a high cabal of banking families, who seek to manipulate each of us by putting microchips in our brains and who sponsor terrorist attacks in Pakistan.”

Mr. Kamran was once a U.S. Fulbright Fellow and could be seen as a poster child for the ineffectiveness of the U.S. government’s public-diplomacy programs. Yet he is far from alone in the conviction that Pakistan is being held back, not by the ignorance of many of its leading citizens but by the conspiracies of a hidden American hand. To give just one example, I have heard Pakistani generals attributing the country’s recurrent floods to the U.S. ionosphere-research program known as Haarp.

So, alongside her courage, Malala Yousafzai has demonstrated wisdom beyond her age in shunning the obscurantism and conspiracy-theory obsession of the society in which she was born. Malala is already a hero of Pakistan’s embattled modernizers, and now her voice has been amplified as never before by the Nobel Peace Prize.