Takeaways

- Russian-Uzbekistani defense ties have grown substantially during the past decade, while Uzbekistan’s military relations with China remain modest.

- Russia, China, and Uzbekistan cooperate best on counterterrorism, transportation, and energy issues.

- Uzbekistan is becoming a linchpin for Russia’s and China’s separate regional integration projects, which have not yet caused significant Sino-Russian friction.

- Uzbekistan could seek additional Russian and Chinese assistance to manage potential threats from Afghanistan.

- The new BRICS Plus format could provide another multilateral structure for deepening collaboration among Russia, China, and Uzbekistan.

Executive Summary

Russian and Chinese goals regarding Uzbekistan are similar in many dimensions, but the two countries differ in how they prioritize and pursue these economic and security objectives. Russia wants Uzbekistan to integrate with Moscow-led regional institutions, deepen defense ties through expanded arms sales and military exercises, and serve as a foundation for Russian economic and energy aspirations throughout Eurasia. Meanwhile, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) initially focused on preventing Uzbekistan’s large ethnic Uyghur population from challenging Beijing’s policies toward Xinjiang. Economic objectives have become more important as Uzbekistan has evolved into a major supplier and transit state for China’s growing natural gas imports. Like their Russian counterparts, PRC policymakers perceive Uzbekistan as a potential linchpin for connecting China with the South Caucasus, the Middle East, and Europe. Neither Russia nor China wants Uzbekistan to have strong military relations with the West.

Uzbekistan has been moving closer to Russia since Shavkat Mirziyoyev became president in 2016. In particular, Russia and Uzbekistan are participating in more military exercises and have increased their defense-industrial cooperation. Nonetheless, Uzbekistan has declined to join major Moscow-led regional organizations. Though Tashkent has adopted a neutral stance regarding Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Western sanctions have helped Russia and Uzbekistan’s economic cooperation grow but have also impeded their defense ties. Meanwhile, China and Uzbekistan have repeatedly upgraded their diplomatic relationship, which they currently define as “an all-weather comprehensive strategic partnership for a new era.”1 PRC-Uzbekistani security ties have focused on counterterrorism, public surveillance, and border security. And China has become Uzbekistan’s leading trading partner and source of foreign loans. From Beijing’s perspective, Uzbekistan has become a critical contributor to China’s energy security.

Uzbekistan’s economic ties with Russia, China, and other countries have substantially grown in the past three years. Mounting Western sanctions led Russian entities to seek new partners, such as China and Uzbekistan, to purchase Russian exports and provide goods and services no longer readily available from the West. Cooperation among Russian, Chinese, and Uzbekistani entities has notably expanded in the energy and transportation domains. Yet sanctions and related developments have spurred Chinese and Central Asian efforts to construct alternative transportation routes that circumvent Russian territory. Uzbekistan achieves economic benefits from these activities, but they make Tashkent more vulnerable to pressure from Moscow and Beijing.

Introduction

This paper begins by reviewing Russian and Chinese security and other goals regarding Uzbekistan, and the following section analyzes how Moscow and Beijing employ multilateral and bilateral initiatives to attain these objectives. Russia’s extensive economic tools sustain its commercial influence regarding Uzbekistan despite the PRC’s growing presence. Meanwhile, China’s security cooperation with Uzbekistan concentrates on counterterrorism, border issues, and public surveillance rather than on conventional military power. The paper’s final section analyzes Sino-Russian cooperation, conflict, and the two countries’ balance of interests and influence concerning Uzbekistan.

Uzbekistan is perhaps the most important Central Asian country for maintaining regional stability. It has the largest population of the five Central Asian countries, exceeding 35 million people. Furthermore, many ethnic Uzbeks reside in neighboring countries, which could lead to internal instability spilling across national boundaries. Additionally, Uzbekistan is the only Central Asian country to border the other four Central Asian states (see figure 1), giving Tashkent leverage to block regional economic and political integration efforts that lack its backing. In contrast with the other Central Asian countries, Uzbekistan does not border Russia or China, which gives Tashkent geopolitical maneuvering room.

Figure 1. Map of Uzbekistan

Source: Author.

Traditionally, Uzbekistan seeks to avoid depending disproportionately on any single foreign actor for political or military needs. The government adheres to the principle of non-intervention in other states’ internal affairs, does not participate in foreign military alliances or blocs, does not deploy its troops to foreign countries, and refuses to allow foreign military bases on its territory. Uzbekistan eschews security ties with Moscow that could compromise its own sovereignty. The government has expanded relations with China and other countries, but not at the expense of national autonomy or regime stability.

Hudson Institute has produced this paper as part of the study “Russia-China Security Interactions in Central Asia: Bilateral and Multilateral Dimensions.” This project analyzes the Sino-Russian relationship in Central Asia through three case studies. The first two papers assess Russia’s and China’s ties with Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, which have the largest economies and populations in the region. The third paper evaluates Sino-Russian interactions within the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). A final paper draws on these three texts and other data to assess Russia’s and China’s overall relationships in Central Asia, consider their future interactions in various scenarios, and evaluate the implications for the United States and its partners. Senior Fellow Richard Weitz is the primary author of the paper. Theodore Horowitz, Konstantin Shchelkunov, Marie Mach, Alexiya Mikerina, Alexander Peris, and Ryan Wright provided research assistance. David Altman, Cole Caven, Ian Maready, Mark Melton, and Hannah Skaggs helped edit and format the text. Hudson Institute would like to thank the Russia Strategic Initiative of the US European Command for funding this study.

Russian and Chinese Goals

The goals of Russia and China regarding Uzbekistan are similar in essential respects. Both countries want to neutralize potential security threats while realizing economic gains through bilateral and multilateral initiatives. However, they differ in how they prioritize and pursue these objectives.

Russian Objectives

The Russian government has tried to intensify bilateral and multilateral ties with Uzbekistan even as Tashkent expands relations with China. For example, Moscow wants Uzbekistan to elevate its connections with the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). Uzbekistan holds observer status in these Moscow-led regional organizations, but Russia hopes it will eventually become a full member. In the interim, Russia has increased weapons sales and the number of joint exercises with the Uzbekistani armed forces. Conversely, the Russian government strives to limit Uzbekistan’s contacts with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

Additionally, Russia perceives Uzbekistan as a linchpin in Moscow’s plans to enlarge its economic and energy ties with Central, East, and South Asia due to the many transportation conduits traversing Uzbekistan’s territory.

Chinese Objectives

After the Soviet Republic of Uzbekistan became an independent country in August 1991, China initially prioritized preventing Uzbekistan’s large ethnic Uyghur population from threatening the PRC government. Economic goals became more important over time as Chinese companies developed infrastructure for importing natural gas from Uzbekistan and other countries through Uzbekistani territory. These overland pipeline shipments obviate the need for Beijing to rely on vulnerable sea lanes susceptible to disruption by pirates or foreign navies.

Growing PRC investment in Uzbekistan, which has more consumers than any other Central Asian country, has also increased the country’s value as China’s commercial partner. Beijing aspires to leverage its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and other projects to expand Uzbekistan’s potential as an east-west transit corridor connecting China with the South Caucasus, the Middle East, and Europe.

Russian Means

Uzbekistan grew closer to Russia after Mirziyoyev became president in 2016. Previously, Mirziyoyev held the post of prime minister under Islam Karimov, who served as Uzbekistan’s first president from its independence in 1991 until his death in 2016. The deteriorating security situation in Afghanistan and Russia’s need for non-Western partners accelerated this alignment. Russia and Uzbekistan have resumed frequent bilateral military exercises and extensive defense-industrial cooperation. Nonetheless, Uzbekistan has resisted Moscow’s entreaties to become a full member of the EAEU or the CSTO.

Diplomatic Tools

Since gaining its independence, Uzbekistan has signed more than 100 bilateral agreements with Russia, including a 1992 friendship treaty, a 1994 military treaty, a 1999 counterterrorism accord, a 2004 strategic partnership treaty, a 2005 treaty on friendly relations, and a 2022 declaration on comprehensive strategic partnership. Through the Council of Regions of Russia and Uzbekistan and other mechanisms, many entities of the Russian Federation and regions of Uzbekistan have adopted additional interregional agreements.2 Uzbekistan has continued a high degree of cooperation within the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), a body that the former Soviet republics formed soon after they gained independence to sustain harmonious economic, cultural, and security ties.3

For example, Uzbekistan’s ministers regularly attend meetings of the CIS Security Council and CIS Defense Ministers.4 The country has also participated in the CIS Air Defense Coordination Committee, the CIS Anti-terrorist Center, the CIS Military Cooperation Coordination Headquarters, and the CIS Council of Commanders of Border Troops. Presidents Vladimir Putin and Shavkat Mirziyoyev meet frequently in other bilateral and multilateral formats. At their 2023 and 2024 summits, the two presidents adopted several dozen economic and security agreements.5

Figure 3. Uzbekistani President Shavkat Mirziyoyev and Russian President Vladimir Putin

Source: “President Shavkat Mirziyoyev Met with President Vladimir Putin,” President of Uzbekistan, October 11, 2017, https://president.uz/en/lists/view/1126.

Nonetheless, Uzbekistan has declined to join some of the newer Moscow-led regional organizations, such as the EAEU, a trading arrangement comprising Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Armenia. Moscow would like Uzbekistan to become a full member of the economic union since the country’s large population and market would increase the organization’s potential.6 Some members of the Russian parliament have called on their government to coerce Uzbekistan into joining the EAEU by threatening to end the visa waiver for Uzbekistani citizens seeking to enter the Russian Federation.7

Uzbekistan has also declined to rejoin the CSTO. It joined the organization only in 2006, several years after its founding, but the government then severely constrained its participation in CSTO exercises, meetings, and other activities. Tashkent also resisted Russia-backed initiatives to strengthen the CSTO and left the organization in 2012 after Moscow insisted on enhancing the body’s military presence in Central Asia. Though Uzbekistani officials did not object to the CSTO’s military intervention in Kazakhstan in January 2022, they made evident they would oppose similar interference in Uzbekistan’s internal affairs.8 Uzbekistani experts expressed confidence that their security forces could handle internal threats and that, if necessary, Tashkent could authorize direct Russian military intervention through bilateral arrangements with Moscow.9 The Russian invasion of Ukraine the following month further depreciated Uzbekistani interest in aligning with Moscow by rejoining the CSTO or becoming a full member of the EAEU.10

Security Ties

At independence, Uzbekistan’s armed forces, while one of the more capable regional armed forces, suffered from limited resources and aging Soviet equipment. For example, the 70,000-man army possessed older T-62, T-64, and T-72 main battle tanks; MIG-29 and Su-27 fighter planes; and Su-25 ground support aircraft. Russia has helped maintain, repair, and upgrade these systems within the framework of the 1999 Treaty between the Russian Federation and the Republic of Uzbekistan on the Deepening of Comprehensive Cooperation in the Military and Military-Technical Spheres. For instance, the Uzbekistani-Russian joint venture UzRosAvia sustained and modernized the Mi-8 and Mi-24 helicopters in service with Uzbekistan and other Central Asian countries.11

The two countries had less success sustaining their joint production of large Soviet-era Il-76 transport planes, Il-78 aerial refueling planes, and Il-114 reconnaissance planes, which the Chkalov Tashkent Aviation Production Association had assembled in Uzbekistan.12 In a practice that Moscow had successfully executed with other former Soviet weapons importers, the Russian government in 2014 forgave almost $1 billion of Uzbekistan’s debt to permit new Russian loans that allowed Uzbekistan to purchase more arms.13 Though Uzbekistani officers can enroll in Russian professional military education, few have done so due to language barriers, Uzbekistan’s own extensive defense education network, and other constraints.14 Additional Russian and Uzbekistani military-industrial personnel train Uzbekistani soldiers on how to employ imported Russian weaponry.

Security ties have improved since Mirziyoyev held prominent bilateral meetings with Putin in Moscow (April 2017) and Tashkent (October 2018).15 In 2017, Russia and Uzbekistan signed an expanded military-technical cooperation agreement that provided for the maintenance and transfer of defense equipment along with joint research and development.16 When Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu visited Tashkent in April 2021, he and his counterpart, Bakhodir Kurbanov, announced their first-ever five-year strategic partnership program. This January, the Russian and Uzbekistani defense ministries adopted a cooperation program for this year and a follow-on 2026–30 strategic partnership program. The 50 joint defense activities in 2025 will include skills training, weapons familiarization, military exercises, and reciprocal visits of delegations.Andrey Belousov, who became Russian defense minister in May 2024, said the new initiatives will launch a “new stage of defense cooperation between the two states.”17

Furthermore, Mirziyoyev launched a reform program to upgrade the military’s Soviet-era technology and the country’s defense industry.18 Since then, Russia has become Uzbekistan’s leading foreign arms seller, supplying more than half of the Uzbekistani armed forces’ defense imports in recent years.19 The major imported Russian weapons systems have included Mi-35M attack helicopters, Su-30SM fighter bombers, Orlan-10 drones, and BTR-82A, Tiger, and Typhoon-K armored personnel carriers.20 The two sides are presently discussing Uzbekistan’s acquisition of more modern Russian air defense systems.21 They are also considering establishing a joint drone production facility in Uzbekistan.22

The Uzbekistani government has strived to increase the domestic manufacture of weapons systems, partly to reduce dependence on foreign military technology.23 Moscow’s decision to invade Ukraine again has underscored the risks of reliance on Russian suppliers, who are often sanctioned or prioritize Russian war needs.24 Uzbekistan’s armaments industry has produced some armored vehicles and military drones.25 However, Moscow’s policy of discounting arms sales for Uzbekistan typically gives Russian systems a superior price-performance value to domestic or foreign alternatives for cutting-edge missions. A 2018 agreement granted Uzbekistan the same opportunity as full CSTO members to purchase Russian arms at the discounted prices charged to Russian customers.26 Though Uzbekistan’s military spending has been rising, its annual defense budget remains below $1 billion.27

The Uzbekistani armed forces also possess some non-Russian-made equipment. These systems include European-made Airbus C-295W light transport aircraft, Airbus utility helicopters, and AS-532 Cougar transport helicopters.28 Furthermore, Uzbekistan has acquired armored combat vehicles and Bayraktar military drones from Turkey.29 It may have recently bought two medium-sized C-390 Millennium military transport aircraft from the Brazilian company Embraer.30 Media reports indicate that Uzbekistan has considered purchasing more advanced Western warplanes, such as French Rafale fighters.31 In August 2024, the United States also allowed Uzbekistan to keep some combat aircraft and helicopters that had belonged to the previous Afghan government—their pilots had flown to Uzbekistan to escape the impending Taliban victory—and provided $64.2 million to repair six of the aircraft.32

In October 2017, at Moscow’s suggestion, Russia and Uzbekistan held their first joint military exercise using Uzbekistan’s Forish Mountain Training Ground.33 They subsequently held regular drills in bilateral and multilateral formats, often simulating maneuvers against threats emanating from Afghanistan.34 Uzbekistan and Russia share an interest in preventing the Uzbekistani-Afghan border from becoming a terrorist gateway to Central Asia and Russia. Shortly after the Taliban takeover in August 2021, Uzbekistan hosted Russian troops in a bilateral drill involving 1,500 total personnel from both sides.35 In addition to exercises with Russia, the Uzbekistani armed forces routinely engage in drills with Central Asian neighbors and select Western partners.36

Notwithstanding former President Karimov’s standoffishness over Moscow’s political-military policies in the post-Soviet space, the ties between the two countries’ internal security, law enforcement, and intelligence organs have always been strong. After meeting with Putin in Tashkent in May 2024, Mirziyoyev stated, “We have agreed to continue developing close cooperation between special services and law enforcement agencies of Russia and Uzbekistan.”37This non-military security cooperation occurs both through bilateral cooperation and within multinational frameworks, such as the CIS and the SCO.

Russian and Uzbekistani security services regularly collaborate against terrorism, extremism, cybercrime, drug trafficking, and other illicit transnational activities, especially as they might emanate from Afghanistan.38 Uzbekistani authorities fully cooperated with Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB) during its investigation of the March 2024 terrorist assault on Moscow’s Crocus City Hall; several of the attackers were Uzbekistani nationals.39 They also helped the FSB identify Uzbekistani nationals suspected of killing General Igor Kirillov, chief of Russia’s Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical Protection Troops, and his assistant on a Moscow street.40 In addition, Uzbekistan’s National Guard signed an agreement with Russia’s Rosgvardiyato cooperate in counterterrorism, training, and preservation of public order.41 The Russian and Uzbekistani interior ministries also cooperate against transnational organized crimes such as illicit migration, narcotics trafficking, and cybercrime.42

During the past decade, Uzbekistan’s security relations with other Central Asian and nearby countries have improved following years of strained ties. For example, Turkey became an important security partner during the past decade. The two countries have signed agreements on defense-industrial cooperation and military intelligence sharing. In March 2021, Uzbekistan hosted special forces from Turkey for three days of drills, with the Turkish chief of general staff attending.43 In April 2025, Tashkent hosted the first independent meeting of the security agency heads of all five Central Asian governments, excluding the security chiefs of China, Russia, and other countries.44

The Uzbekistani armed forces have also engaged in bilateral drills with other Central Asian countries, without Russian and Chinese participation. The Commonwealth 2022 exercises with Tajikistan in Termez, on Uzbekistan’s border with Afghanistan, rehearsed joint frontier defense a year after the Taliban returned to power.45 In July 2023, Uzbekistan hosted members of the Azerbaijani armed services in UZAZ-2023.46 In December 2024, Kazakhstani and Uzbekistani military forces conducted their annual Kanzhar joint tactical exercise. The 10-day Kanzhar-2024 drills simulated urban combat at the Forish Mountain Training Ground in Uzbekistan’s Central Military District.47 From July 8–17, 2024, Uzbekistan joined Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Tajikistan in the Birlestik-2024 (United-2024) multinational exercises. Some 4,000 military personnel drilled in Kazakhstan’s Mangystau Region near the Caspian Sea port of Aktau. The ground, air, and naval forces rehearsed fighting illegal armed groups to enhance interoperability and regional cooperation.48

Though these drills have not aroused public Russian opposition, Moscow has pressed Uzbekistan to limit its security ties with Western countries. After the Pentagon withdrew from Afghanistan in 2021 and initiated discussions with Uzbekistan about establishing over-the-horizon counterterrorism capabilities, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov preemptively claimed that “all our Central Asian friends say that they don’t want the deployment of the US (troops) or any other NATO countries.”49

Uzbekistan has adopted a formally neutral stance regarding the Russia-Ukraine War. The government has consistently urged an end to the fighting without proposing a detailed peace process. Like other Central Asian governments, Uzbekistan has never accepted Moscow’s contested annexations of other countries’ territories, including the occupied regions of Georgia in 2008, Crimea in 2014, and eastern Ukraine since 2022. Furthermore, the authorities have constantly warned its citizens that participating in foreign wars violates Uzbekistani law; they have arrested several Uzbekistani nationals for fighting in Ukraine.50 According to estimates, dozens of Uzbekistani nationals have died fighting as mercenaries for Russia.51 They appear to have fought for promises of money, Russian citizenship, or early release from prison.52 Some Russian officials have criticized the Uzbekistani government’s stance. Sergei Mironov, leader of the A Just Russia—For Truth faction in the Russian State Duma, stated that Uzbekistani nationals residing in Russia who receive economic and social benefits from the Russian government should “defend the country that feeds you.”53

Conversely, Uzbekistani entities have provided some dual-use assistance that aids Russia’s war effort. In particular, Russian munition plants have imported cellulose (cotton pulp, a main ingredient of nitrocellulose, a.k.a. guncotton) from Russian-owned factories in Uzbekistan, the Fergana and Jizzakh Chemical Plants, to manufacture explosives and propellants for missiles and artillery shells.54 These imports, which have legitimate commercial applications, have risen sharply since 2022.55 The US government has sanctioned a few Uzbekistani entities for assisting Russia’s military-industrial complex. For example, US authorities charged the Uzstanex company with transferring banned machine tools to Russia through transshipment by a PRC entity.56 Western governments’ curtailment of natural gas purchases from Russia also drove Gazprom to pursue more gas sales to Uzbekistan and other Central Asian countries, allowing Uzbekistan to buy Russian gas at prices lower than Russia charges China.57

Economic and Energy Connections

The Russian Federation has remained an important economic partner of Uzbekistan. According to Russian government data for 2023, Russia sold $6.54 billion worth of products to Uzbekistan (its eighth-highest export destination) while importing $3.02 billion that year (ranking second among Uzbekistan’s exporters, after China).58 The two governments have set ambitious plans to triple their bilateral trade to $30 billion by 2030.59 Uzbekistan purchases Russian refined petroleum, automobiles and other vehicles, equipment, agricultural products, timber, pulp, paper, chemical and mineral products, and metals. Uzbekistan also began importing Russian gas via Kazakhstan in October 2023.60 Meanwhile, Russia buys cotton yarn, textiles, metals, chemical goods, and agricultural and food products (which benefit from a special “green corridor”).61 The two governments have reduced their reliance on third-party currencies, which might be more exposed to international sanctions. In 2024, more than 70 percent of Russian-Uzbekistani commercial transactions were settled in their national currencies.62

Russian business elites have benefited from Mirziyoyev’s economic reforms, which relaxed restrictions on incoming foreign investment and currency exchanges.63 Russia is a leading source of foreign investment in Uzbekistan due to the operations of large Russian state corporations such as Rosatom, Gazprombank, VEB.RF, Gazprom, and Lukoil.64 For instance, the value of Lukoil’s projects in Uzbekistan amounts to $8 billion.65 Of 15,000 companies in Uzbekistan with foreign capital, approximately 3,000 are joint Russian-Uzbekistani ventures.66 Valued at over $13 billion, these operate in the aerospace, automotive, chemical, energy, metallurgy, mining, pharmaceutical, telecommunications, textile, and other sectors.67

Uzbekistan signed a memorandum of cooperation with Russia’s state nuclear energy corporation, Rosatom, in November 2017 to develop Uzbekistan’s nuclear infrastructure.68 Though the initial concept foresaw Russian construction of a 2.4 gigawatt nuclear plant in Uzbekistan, in May 2024, the two governments announced a scaled-back plan to build a 330 megawatt plant powered by six small reactors. Analysts speculate that the Uzbekistani partners revised the plans to contain costs.69 Rosatom began manufacturing equipment for Uzbekistan’s first small reactor in May 2025.70 Opponents of the project challenge its economic and technical logic and warn that its construction would enhance Moscow’s leverage over Uzbekistan, which would need Russian assistance to build and operate the plant.71

The millions of Uzbekistani nationals who pursue temporary employment in Russia provide another source of Russian influence. In 2022, over 40 percent of the 3.47 million labor migrants in Russia were Uzbekistani nationals.72Their remittances amounted to $8.5 billion in 2023, equating to some 18 percent of Uzbekistan’s gross domestic product and significantly exceeding remittances from other countries.73 The Russian government encourages migrant workers from Uzbekistan by offering visa-free entry and other inducements but wants Uzbekistani authorities to ensure that potential migrants know some Russian and adhere to “Russian laws and rules of conduct for foreigners.”74 Russian authorities can impede their activities to exert leverage.

Soft Power and Influence Assets

Though only a small percentage of Uzbekistan’s population is ethnically Russian, knowledge of the Russian language is extensive due to the legacy of the Soviet era and the teaching of basic Russian in many schools. In November 2024, Uzbekistan ratified a treaty to establish the International Organization for the Russian Language. The organization works to support the Russian language as a means of international communication and as an instrument for advancing historical and scientific knowledge and literature. Russian TV broadcasts with pro-Kremlin messaging are widely accessible in Uzbekistan.75 According to opinion polls, the public views Putin positively, notwithstanding his invasion of Ukraine. Furthermore, respondents in Uzbekistan view Russia more favorably than they assess China or the United States.76At the elite level, more than 56,000 students from Uzbekistan study in Russian universities, either in Russia or at the 14 Russian colleges and joint educational institutions operating branches in Uzbekistan.77 Through his charitable foundation, Russian-Uzbek businessman Alisher Usmanov is working with the Russian and Uzbekistani Ministries of Education to elevate Russian language instruction in Uzbekistan by retraining existing teachers and posting Russian teachers in Uzbekistani schools.78 Usmanov, one of Uzbekistan’s most influential pro-Russian figures, is subject to various Western sanctions.79

Nonetheless, when Lavrov paid his respects at the Eternal Flame in Samarkand in an April 2025 trip to Uzbekistan, the foreign minister evoked controversy when he expressed surprise that the inscription on the Motamsaro Ona (Grieving Mother) memorial for World War II fallen soldiers was in Uzbek and English but not Russian.80 The leader of the Milliy Tiklanish (National Revival) party, Alisher Qodirov, complained that “Russian politicians seem to be trying every possible way to portray Uzbekistan as disrespectful to Russian language and culture. . . . Lavrov surely understands that forced respect and invented needs only create the opposite effect.”81 Some prominent Uzbekistani politicians have objected to “chauvinist” messaging on Russian TV, such as Russian nationals calling for Uzbekistan’s annexation, and advocated reducing such programming in Uzbekistan.82 In response to threatening remarks from some Russian media commentators, the Uzbekistani legislature and president enacted an Undesirable Foreigner Law that allows the government to impose a five-year entry ban and financial sanctions on foreigners who make “public calls or actions that contradict the state’s sovereignty, territorial integrity and security, provoke interstate, social, national, racial or religious hostility or discredit the honor, dignity and history of the people of Uzbekistan.”83

Chinese Means

Uzbekistan is unique among the five Central Asian countries because it does not border the PRC. Still, Uzbeks share a long history of ties with the Chinese people, dating back more than 1,000 years. During the era of the Great Silk Road, Uzbekistan’s territory, especially the city of Samarkand, was a prominent conduit for China’s east-west trade. Moscow’s control over Uzbekistan and the rest of Central Asia during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries temporarily ruptured these contacts, but the Soviet Union’s disintegration in 1990 created a foundation for rebuilding ties. The PRC and Uzbekistan established diplomatic relations in 1992, and their political, economic, and security ties have grown considerably since then.

Diplomatic Tools

During the mid-2000s, various strains worsened Uzbekistan’s links with many Western governments, leading Tashkent to strengthen ties with alternative partners like China. In 2005, President Karimov made a breakthrough trip to Beijing. During this visit, the PRC and Uzbekistan signed a treaty of friendship, cooperation, and partnership, and its principles still govern their relationship. In June 2012, Uzbekistan and China signed a declaration on strategic partnership in which they pledged to intensify ties. This became a comprehensive strategic partnership in 2016.84

When Mirziyoyev traveled to Beijing on a state visit in January 2024, he and Xi Jinping proclaimed “an all-weather comprehensive strategic partnership for a new era.”85 The Uzbekistani government regularly sides with the PRC’s interpretation of sensitive issues such as Taiwan’s sovereignty (embracing Beijing’s “one-China principle”), Xinjiang’s Uyghurs (pledging to fight the “three evil forces” of terrorism, extremism, and separatism), and international order (praising Xi’s Global Security Initiative, Global Civilization Initiative, and Global Development Initiative).86

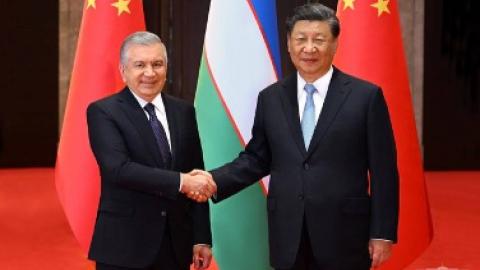

Figure 4. Uzbekistani President Shavkat Mirziyoyev and PRC President Xi Jinping

Source: “Uzbek and Chinese Leaders Define Priorities for Deepening Comprehensive Strategic Partnership,” President of Uzbekistan, May 18, 2023, https://president.uz/en/lists/view/6341.

Security Ties

Since independence, Uzbekistani authorities, with Chinese encouragement, have prevented their country’s large ethnic Uyghur community from engaging in political activities that could exhibit anti-Beijing manifestations. Furthermore, Uzbekistan has allocated more resources to its border guards and special forces. Under a barter arrangement, the PRC gave Uzbekistan HQ-9 (FD-2000) surface-to-air interceptor missiles in return for natural gas.87 Uzbekistan has also purchased Chinese-made Wing Loong strike drones.88 The two governments are also reportedly discussing Uzbekistan’s purchase of Chinese multirole jet fighters, possibly the JF-17 Thunder that China co-developed with Pakistan.89 However, Russia remains Uzbekistan’s primary weapons supplier.

PRC-Uzbekistani security cooperation primarily involves other institutions besides the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). In 2019, the Chinese People’s Armed Police held a counterterrorism training drill with Uzbekistan’s National Guard, whose internal security role has grown under Mirziyoyev.90 Additionally, China’s powerful Ministry of Public Security has hosted hundreds of Uzbekistan’s Ministry of Internal Affairs employees for briefings and training related to counter-narcotics and counterterrorism.91 Furthermore, the Chinese and Uzbekistani police academies—the People’s Public Security University of China and Uzbekistan’s Academy of the Ministry of Interior Affairs—signed a memorandum of cooperation, which included establishing joint courses.92 The Chinese overseas police station in the city of Syr Darya could allow Chinese authorities to monitor PRC nationals in Uzbekistan.93

Uzbekistan relies heavily on Chinese telecommunications companies, including CITIC Group, Costar Group, HikVision, and especially Huawei, a leading internet and wireless equipment provider.94 These dual-use technologies (e.g., internet services, biometric databases, facial recognition, and safe city projects) enhance both Uzbekistan’s economic development and its domestic surveillance capabilities. Western analysts believe the Chinese government can access substantial personal, commercial, and government data from Uzbekistani entities that employ PRC internet and wireless companies.95 The difficulties Western and even Russian competitors in Uzbekistan experienced while doing business under Karimov’s quasi-autarchic policies contributed to the subsequent dominant position of Chinese telecommunications companies.96

Economic and Energy Ties

According to official PRC data, in 2023 China exported $12.1 billion worth of goods to Uzbekistan while importing $1.8 billion worth.97 Due to these very imbalanced flows, that year the PRC was Uzbekistan’s fourth-largest export destination, whereas Uzbekistan ranked only as China’s forty-fourth-highest national export purchaser.98 Chinese exports to Uzbekistan have surged since 2022, suggesting that some goods the PRC cannot send directly to Russia due to Western sanctions transship through Uzbekistan.

Uzbekistan mainly exports energy (especially petroleum gas), minerals, metals, food products, and cotton to China while importing automobiles, machinery, equipment, and digital technologies. The gradual dismantling of Uzbekistan’s Karimov-era trade protectionism structure has facilitated the diversification of exports beyond cotton, but the legacy of import substitution has limited Uzbekistan’s purchases of consumer goods compared with those of other Central Asian countries. Its exports to China and other countries may grow if its government realizes plans to expand production of rare earth minerals.99

China’s annual investment flows (defined in Uzbekistan as both loans and foreign direct investment) into Uzbekistan have amounted to as much as $3 billion in recent years, substantially exceeding the capital coming from Russia.100 The aggregate value of PRC foreign investment into Uzbekistan approximates $14 billion; Uzbekistan’s outstanding loans to China amount to almost $4 billion; and more than 3,400 enterprises with Chinese capital now operate in Uzbekistan’s agriculture, automotive, chemical, construction, energy, healthcare, telecommunications, textile, and other sectors.101 PRC firms such as Huawei are some of Uzbekistan’s largest foreign direct investors. Various China-Uzbekistan business conferences provide opportunities for commercial entities from the two countries to negotiate specific commercial and financial deals. For example, during Mirziyoyev’s January 2024 visit to China, he participated in a bilateral investment forum in Shenzhen.102 Chinese capital and technology are developing Uzbekistan’s renewable green energy sector. PRC investors are helping build wind and solar power plants, construct electric vehicle factories, and mine uranium for nuclear power.103

The 2023 China–Central Asia Summit adopted a Program for the Development of Comprehensive Strategic Partnership in the New Era Between Uzbekistan and China for 2023–2027. Within this framework, the PRC and Uzbekistani governments have reached dozens more detailed intergovernmental agreements, sometimes at regular BRI meetings. The BRI supports the construction of railways, roads, pipelines, seaports, and other infrastructure to facilitate Chinese trade and investment. Its China–Central Asia–West Asia Economic Corridor encompasses Uzbekistan, whose territory offers potential routes connecting China with Central Asia, the Middle East, and southern Europe. Beijing and Tashkent perceive this process as a win-win partnership. China strives to make Uzbekistan a critical transit hub between Asia and other regions, which helps Uzbekistan attract international trade and foreign investment.104

Furthermore, PRC policymakers value Uzbekistan’s contributions to China’s energy security. Chinese companies have improved Uzbekistan’s infrastructure to produce and transfer gas. Since China and Uzbekistan do not share a border, the energy pipelines connecting them must traverse other countries. In the past, when Uzbekistan produced more natural gas than it needed for domestic consumption, it sold gas directly to the PRC. Even after rising domestic demand transformed Uzbekistan into a natural gas importer, the three Central Asia–PRC pipelines that traverse its territory have supplied 50–60 billion cubic meters (bcm) of natural gas to the PRC, amounting to about one-fifth of China’s gas imports.

Soft Power and Influence Assets

The study of Chinese language and culture is not widespread in Uzbekistan, but hundreds of students enroll in PRC academic institutions, including some branches of Chinese universities in Uzbekistan. The country hosts two Confucius Institutes: the Institute of Chinese Language and Culture at the Tashkent State University of Oriental Studies was established in 2005, and the Institute of Chinese Language and Culture at the Samarkand State Institute of Foreign Languages has been operating since 2013.105 These institutes offer classes to thousands of students on Chinese language and culture and PRC values. Still, Chinese TV shows are less popular than Russian TV broadcasts, while some Uzbekistani nationals fear exploitation by Chinese businesses.106

Following the removal of COVID-19 travel restrictions, reciprocal tourism between Uzbekistan and China has rebounded to pre-pandemic levels. The two governments are also implementing a 30-day, visa-free travel regime.107 And while some Uzbekistani newspapers adopt pro-PRC positions, often echoing narratives from the Chinese Communist Party, others cover Chinese affairs infrequently or without endorsement.108

China has directed language outreach to Uzbekistan’s national security establishment. For example, the PRC supports Chinese language courses at the Uzbekistani National Guard’s Military-Technical Institute.109 Furthermore, the PLA has pursued educational exchanges with Uzbekistan’s Armed Forces Academy.110

Russia-China Interactions and Implications

Since Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, Uzbekistan’s economic ties with Russia, China, and other countries have substantially expanded. For example, Western sanctions led Russian commercial entities to redirect trade away from Europe and toward Asian partners, especially China and Central Asia. In addition, Uzbekistan and other Central Asian countries have provided pathways by which goods potentially subject to Western sanctions can enter Russia.

As a result of these developments, China has displaced Russia as Uzbekistan’s leading trade partner in terms of overall turnover and imports, though the PRC ranks only as Uzbekistan’s second-highest export destination. In 2023, China accounted for slightly more than one-fifth (22 percent) of Uzbekistan’s foreign trade.111 In 2017, Uzbekistan’s trade with China was approximately $4.2 billion, trailing its $4.5 billion volume with Russia.112 In 2022, Russia still had a slight lead: Russian-Uzbekistani trade was $9.39 billion, versus $9.06 billion for PRC-Uzbekistani trade.113 By 2023, though, Uzbekistan’s turnover with China surged to almost $14 billion (i.e., increasing by over 50 percent in just one year), substantially exceeding its nearly $10 billion in trade with Russia that year.114

Transport Partnerships

Meanwhile, Western sanctions on Russia and other developments following Moscow’s attack on Ukraine have spurred Central Asian and Chinese interest to construct transportation routes that circumvent sanctioned Russian territory. In the security realm, moreover, the war and sanctions have stalled the growth of Russian-Uzbekistani defense relations and curtailed Uzbekistan’s interest in deepening ties with Moscow-led regional institutions, such as the CSTO or the EAEU. Uzbekistan’s security managers continue bilateral defense cooperation with Russia while also collaborating with China and other partners.

Though under discussion for decades, the planned China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan (CKU) railway has recently become a central issue for their trilateral relations (see figure 5). The railway would provide the shortest transport route from the PRC to the countries of Central and South Asia. It could help all three countries ship goods faster and cheaper between China and Europe or the Middle East through Central Asia.

Figure 5. Approximate Route of China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan Railway

Source: Adapted from Zorigt Dashdorj, “A New Railway Highlights Regional Dynamics in Central Asia,” Geopolitical Intelligence Services, October 18, 2024, https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/railway-central-asia/.

Note: Because China uses a narrower gauge, the track change will occur at Makmal. Work on the route officially started in December 2024, and construction of the three longest tunnels started in April 2025. Previously, the three countries considered a more direct southern route that would have connected Kashgar and Andijan via Irkeshtam Pass and Osh, Kyrgyzstan. For more, see “To Secure Exports to Europe, China Reconfigures Its Rail Links,” The Economist, April 6, 2025, https://www.economist.com/china/2025/04/06/to-secure-exports-to-europe-…; and Luo Wangshu, “Work Begins on Three Critical Tunnels of China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan Railway,” China Daily, April 29, 2025, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202504/29/WS6810e628a310a04af22bceab.ht….

In the past, Kyrgyzstan’s political instability and weak economy, the three countries’ diverging views of the optimal rail route, the challenging terrain, and the different railway gauges used in China and Central Asia stalled progress.115 Both Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan have always been enthusiastic about the line, but Beijing proved reluctant to commit since the PRC would have to provide most of the funding, especially to help Kyrgyzstan complete its project work. Additionally, neither Russia nor Kazakhstan wanted to see the CKU built since it would compete with their alternative Middle Corridor routes.116

However, Russian resistance has waned as Moscow’s war on Ukraine became a stalemate and Western sanctions made Russian diplomacy more solicitous of Chinese and Central Asian con117 Meanwhile, the unending sanctions intensified Chinese interest in developing east-west transit conduits that circumvented Russian territory. As a result, the PRC recently became more enthusiastic about the deal.118 The governments of China, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan held an official launch ceremony for the railway at the end of 2024. Though many questions about its construction, timeline, and finances remain, the railway’s completion should bring commercial benefits to all three states while enhancing China’s economic influence in Central Asia.119

Conversely, the availability of another transportation corridor that circumvents sanctioned Russian territory could further erode Russia’s previous dominance over Eurasian east-west transportation networks. The Uzbekistani government aims to extend these benefits. In January 2025, it authorized a five-year plan to increase freight through Uzbekistan and the Middle Corridor by decreasing costs and increasing trade routes.120

Energy Cooperation

Russia, China, and Uzbekistan’s energy cooperation encompasses much of Eurasia. Three natural gas pipelines traverse Uzbekistan: the Soviet-era Central Asia–Center pipeline designed to transport gas northward through European Russia, the newer Bukhara–Urals Russian pipeline, and the 2,268 mile (3,650 kilometer) Central Asia–China pipeline that begins in Turkmenistan.

A decade ago, Uzbekistan committed to sell natural gas to China. But in recent years, rising domestic consumption and falling domestic production—from 58.5 bcm in 2018 to 46.7 bcm in 2023—have compelled Uzbekistan to import gas from Turkmenistan, and increasingly Russia, to meet its contractual obligations to the PRC.121 Though Tashkent plans to cease exporting natural gas due to these supply and demand changes, substantial Central Asian gas flows to China will continue through pipelines that run through Uzbekistani territory.

This transformation in the Eurasian gas market helps promote Sino-Russian cooperation and provides Moscow and Beijing with additional leverage over Tashkent, which they might exploit to influence Uzbekistan’s policies.122 Since Uzbekistan is a doubly landlocked country, it must cooperate with other Eurasian countries to reach global markets. A possible precursor of such intimidation occurred in November 2022 when Putin abruptly called for a “gas union” among Russia, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan. Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov said that such a mechanism would help coordinate natural gas shipments between them and to other countries, such as China. The Uzbekistani minister of energy, Jurabek Mirzamahmudov, insisted that gas agreements with Russia had to be commercial technical contracts without any “political conditions.”123

Even so, expectations that Western countries could limit economic ties with Russia indefinitely have amplified Russian aspirations to expand exports to customers throughout Asia, including to—or through—countries ruled by anti-US regimes, such as Iran and Afghanistan.124 Uzbekistan and other Asian countries will gain transit revenue and other commercial benefits from these Russia-related transactions, but the increasing economic interdependence creates vulnerabilities that Moscow can manipulate.

Uzbekistan and the West

Neither Russia nor China wants Uzbekistan to have strong military relations with the West. These ties have waxed and waned. During the 1990s, Karimov adopted a wayward path from Moscow.125 In 1999, Uzbekistan joined a coalition of Westward-leaning former Soviet republics, identified as the GUUAM bloc—which included Georgia, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, and Moldova. This group never gained much influence and soon fell into disuse.

The 9/11 terrorist attacks against the United States resulted in the Pentagon establishing a substantial military presence in Afghanistan and Central Asia. Starting in October 2001, the Uzbekistani government allowed US forces to use its airspace and the large Karshi-Khanabad (K2) air base in Qashqadaryo Province near the country’s border with Tajikistan. This air base provided extensive support for the Soviet campaign in Afghanistan but ceased military operations following the USSR’s collapse. The host-nation agreement did not permit US forces to engage in direct combat support operations from K2 but did allow search-and-rescue flights into Afghanistan. The US Army established Camp Stronghold Freedom, a logistics base, there. The United States and its NATO allies then relied on Uzbekistan as a central transportation hub to Afghanistan due to its superior military infrastructure. Its territory provided some of the best road-and-rail networks between Afghanistan and Central Asia, such as the Termez to Mazar-i-Sharif route.

In March 2002, the Uzbekistani and US governments signed a strategic partnership and cooperation framework agreement that expanded military, diplomatic, and economic collaboration between the two countries.126 Uzbekistan then obtained hundreds of millions of dollars in foreign military financing, Freedom Support Act funds, and nonproliferation and counterterrorism support. But in 2004, the US Congress forbade the Bush administration from giving military assistance to Uzbekistan unless the State Department was able to certify that the country was making progress toward its commitments, including respect for human rights and economic reform; the State Department could not do so.

Uzbekistani leaders soon perceived the growing Western presence in their region more as a security liability than as a benefit. Western support for so-called color revolutions in the former Soviet republics—protests that overthrew the governments of Georgia, Ukraine, and Kyrgyzstan in the early 2000s—aroused fears in Uzbekistan that their allies’ democracy-promotion efforts threatened their rule. The break between Washington and Tashkent came in 2005 when the Uzbekistani military employed NATO-provided weapons and training to suppress demonstrations in the city of Andijan. Western leaders denounced the attack and urged neighboring governments to respect the asylum claims of protesters, leading Tashkent to expel the Pentagon from the K2 base. It took several years for Uzbekistan-US relations to begin to recover. Then, starting in 2008, the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan transshipped substantial material via the Northern Distribution Network, which bypassed Pakistan by traversing Russia, the Caucasus, and Central Asia.

Uzbekistan receives military training through NATO’s Partnership for Peace program and participates in the US National Guard’s State Partnership Program. Since 2012, Uzbekistan and the Mississippi National Guard have conducted several hundred partnership engagements, including military-to-military exchanges, key leader meetings, and exercises (see figure 6).127 US Central Command (CENTCOM) has also sustained regular discussions, workshops, trainings, and other engagement opportunities with the Uzbekistani armed forces.128 According to CENTCOM congressional testimony, “Mirziyoyev has reaffirmed the country’s unwillingness to allow other nations to establish military bases in Uzbekistan, its restriction against aligning with foreign military or political blocs, and its self-imposed restriction against any type of expeditionary military operations. Despite these limitations, our bilateral mil-to-mil efforts are focused on helping the Uzbeks improve border security, enhance their counter-narcotic and counter-terrorism capabilities, and prevent the return of foreign fighters into the country.”129 Though the United States and Uzbekistan share intelligence regarding terrorist threats, the Uzbekistani government does not permit the US military to attack terrorist targets in Afghanistan or other countries from its territory.130

Figure 6. Members of Mississippi Air National Guard and Uzbekistan National Guard Tour C-17 Globemaster III in Flowood, Mississippi

Source: Lt. Col. Teri Dawn Neely, “State Partner Visits Mississippi,” US Air National Guard, April 26, 2022, https://www.dvidshub.net/image/7714360/state-partner-visits-mississippi…;

From 2021 through 2024, Uzbekistan and the United States convened annual strategic partnership dialogue meetings in Washington and Tashkent. At their November 2024 session, they agreed to elevate the status of their annual meetings to an enhanced strategic partnership dialogue.131 The Uzbekistani Foreign Ministry has recently launched several projects to strengthen relations with the United States. These initiatives encompass high-level bilateral engagement with senior US executive and legislative branch officials, efforts to attract US investment and raise the country’s human rights ratings, and multilateral outreach within the C5+1 format. The C5+1 summit brings together the ministers of the five Central Asian countries Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan plus the United States.

In his January 2025 congratulatory letter to newly inaugurated US President Donald Trump, Mirziyoyev expressed gratitude for America’s “consistent support of its independence, sovereignty, and territorial integrity.”132 US Secretary of State Marco Rubio has expressed appreciation for Uzbekistan’s cooperation on immigration, terrorism, and energy.133 At the end of April, the Uzbekistani government organized a charter flight to remove 131 Uzbekistani, Kazakhstani, and Kyrgyzstani citizens who were in the United States unlawfully. The US Embassy in Uzbekistan described the operation as the “first in which a US partner proactively provided a dedicated flight to repatriate its citizens” illegally present in the United States, stating that the initiative “exemplifies the productive and growing cooperation between the” two countries and Uzbekistan’s “role as a trusted and proactive partner in the realm of international security.”134 The US Department of Homeland Security said, “This operation, in which Uzbekistan fully funded the deportation of their own nationals, underscores the deep security cooperation between our nations and sets a standard for US alliances.”135 Uzbekistan’s Foreign Ministry said that it organized the repatriation flight, which included approximately 100 Uzbekistani citizens, “on the basis of humane and legal principles that ensure the dignified and safe return of its citizens” having visa or related problems in the United States.”136 Meanwhile, the two governments and private companies from these countries are developing plans to mine Uzbekistan’s potential vast deposits of critical minerals.137

Counterterrorism Partnerships

Uzbekistan has been an active member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization since its establishment in 2001, and Tashkent has hosted the SCO’s Regional Anti-Terror Structure since the body’s creation in June 2004.138 Although it typically sends only staff officers and observers to the large-scale SCO exercises, Uzbekistan has participated in some of the organization’s smaller-scale counterterrorist drills. Moscow, Beijing, and Tashkent regularly partner within the SCO and on some regional economic and security initiatives, including regarding Afghanistan. The new BRICS Plus format—which took effect in January 2024 and includes the original members Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa as well as new participants—may also provide another multilateral structure for deepening cooperation among Russia, China, and Uzbekistan. When he attended the BRICS Plus summit in the Russian city of Kazan in October 2024, Mirziyoyev said his government intended to collaborate closely with the BRICS New Development Bank to support priorities such as an innovative digital economy, artificial intelligence, e-commerce, supply chain logistics, and green energy projects.139

The Uzbekistani government relies primarily on its military and internal security forces to counter transnational terrorism threats. Though ethnic Uzbeks have been involved in recent terrorist incidents in Russia, Europe, and the United States, many of these individuals left Uzbekistan long ago. There have not been major terrorist incidents inside Uzbekistan itself in recent years. However, developments in Afghanistan could adversely impact Uzbekistan’s security. The two countries share an 85 mile (137 kilometer) border, and many ethnic Uzbeks reside in Afghanistan. Before the Taliban returned to power in August 2021, Uzbekistan helped build Afghanistan’s roads, railroads, bridges, telecommunications, and other national infrastructure. Since then, Uzbekistan has been one of the most forward-leaning Central Asian governments in trying to establish good relations with the new Taliban regime.

The Uzbekistani government reopened the Afghanistan–Uzbekistan Friendship Bridge, declined to champion the rights of ethnic Uzbeks in Afghanistan, and took other measures to restore normal economic ties.140 Uzbekistan’s national railway company wants to construct a China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan–Afghanistan transport corridor, which would facilitate its access to Indian Ocean seaports and maritime trade routes.141 The government also favors a related Trans-Afghan Railway that would convey cargo between southern Uzbekistan and Pakistan via Afghanistan.142

Nonetheless, since 2021, Uzbekistan’s armed forces have participated in several exercises with Russian and Central Asian countries to fortify their joint defenses against threats from Afghanistan.

Abbreviations

BRI Belt and Road Initiative

BRICS Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa

CENTCOM US Central Command

CIS Commonwealth of Independent States

CSTO Collective Security Treaty Organization

EAEU Eurasian Economic Union

FSB Federal Security Service (Russia)

NATO North Atlantic Treaty Organization

PLA People’s Liberation Army

PRC People’s Republic of China

SCO Shanghai Cooperation Organization