For economic, historical, political, and security reasons, Europe is vital to the United States’ national security interests, and it will remain so for the foreseeable future.1 Further, American boots on the ground in Europe are a cornerstone of transatlantic security, undergirding the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and providing the US with significant and often underappreciated benefits.

America’s presence and the network of US bases across Europe are vital to NATO’s mutual defense guarantee, Washington’s ability to project power, and US ties with its closest partners.2 As of June 2025, the US maintained 67,355 permanent active-duty troops in Europe. Sources estimate the US total force posture at 84,000 troops, meaning around 16,600 US troops are on rotational deployments to Europe at any given time.3

Over the past 20 years, the US has grown its ties with the three Baltic states: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. And for the past decade, Washington has rotated small contingents to these nations to bolster security. Turning away from this commitment is shortsighted and dangerous. The Baltic states have proven repeatedly to be model allies, and a US presence in those nations has an outsized impact on shaping perceptions in the region and deterring a possible Russian conventional attack. The US should therefore commit to maintaining its force posture in the region.

Deterring the Escalating Russian Threat

The Trump administration is likely to release a new National Defense Strategy and an updated Global Posture Review, the last of which was completed in 2021, early next year. The security situation in the European theater has changed drastically in the intervening four years, which should drive US thinking on global force posture.

The 84,000 US troops in Europe represent roughly 6 percent of US active-duty personnel,4 a small commitment that makes a significant impact in a key region. The permanently based component of that presence is historically small. The US has stationed an average of 93,852 permanent forces in Europe since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991.5 For this modest commitment, the US helps ensure that NATO deterrence remains credible, guarantees access to a network of strategically located bases, and garners greater political influence in Europe.

The administration has signaled it wants to rebalance US troop dispersal to emphasize the threat from China, homeland defense, and security in the Western Hemisphere. This focus is written explicitly in the 2025 National Security Strategy, which states that “the United States will reassert and enforce the Monroe Doctrine to restore American preeminence in the Western Hemisphere.”6 Meanwhile, the transatlantic region faces a crucial moment. The Russian war against Ukraine and the Kremlin’s shadow war against the West—which includes aerial incursions, arson, cyberattacks, Global Positioning System jamming, influence peddling, operations to map European defense networks, targeted assassinations, and sabotage—suggest that Moscow plans to escalate its aggression in the future.

Moscow has comprehensively reordered Russia’s economy and society for military expansion, and the regime’s survival is indelibly tied to its imperial aggression. Therefore, if fighting were to end in Ukraine, Vladimir Putin would likely seek a new outlet for this military capacity. The Kremlin may view the next few years as a window of opportunity to strike Europe before NATO can rebuild its military deterrent, and pulling US forces out of Europe would exacerbate the situation. As I have previously written, “Any drawdown is inadvisable, but a haphazard one that pulls the rug out from under European NATO members before they can stand up replacement formations to backfill any resulting gaps would be the most damaging scenario.”7

The Baltic states, which are among the most likely targets of future Russian kinetic operations, understand this threat. In November, Estonian Minister of Foreign Affairs Margus Tsahkna testified that, based on Moscow’s military posture, Russia would “return to our Baltic borders with even more troops and military equipment than they had before the full-scale invasion” in “two to three years, or less.”8 Karolis Aleksa, Lithuanian vice minister of defense, noted earlier this year that “the threat is real. We know that from our history.”9

NATO can signal resolve within the alliance by increasing its presence in the Baltics. An expanded allied force presence in the region is not provocative—but a weak posture certainly is. American military leaders, including former Supreme Allied Commander Europe General Christopher Cavoli, have emphasized the importance of ground forces for deterrence.10 Lithuania’s 2025 National Threat Assessment concluded that “strengthening the Baltic defence and deploying allied forces on NATO’s eastern flank are key factors in deterring Russia from military conflict in our region. This increases the costs of a potential military conflict to Russia and makes it less likely that such a conflict would be localised and would not involve the other members of the alliance.”11 Some allies are stepping up. For example, Germany inaugurated an armored brigade permanently based in Lithuania in May that will reach full operational capacity by the end of 2027.

An on-the-ground presence in the region is important not only for signaling Moscow, but also because NATO cannot take for granted its ability to return forces to the region in the event of a hot conflict. European Union officials believe that “it would take roughly 45 days to move an army from the strategic ports in the west to countries bordering Russia or Ukraine.”12

Therefore, placing US forces in the Baltics serves a valuable role in deterrence. Major General Andrus Merilo, commander of the Estonian Defense Forces, said in April, “US boots on the ground are crucial for credible deterrence and contribute directly to nuclear deterrence.”13 Moscow would see a US withdrawal from the region as a signal of Washington’s weakening resolve to defend its Baltic allies. As I have noted, “US forces based in Europe are the steel that gives NATO defense plans strength in the eyes of Russia.”14

Baltic Military Spending

The Baltics spend a significant portion of their gross domestic products on defense. This year, Lithuania will spend 4 percent of GDP on defense, Latvia 3.73 percent, and Estonia 3.38 percent—the second-, third-, and fourth-highest totals in NATO, respectively.15 In June, Latvian Minister of Foreign Affairs Baiba Braže stated that her nation would attain the new NATO benchmark of 5 percent by next year.16 In April, Estonia approved a new defense funding bill that will increase its spending to 5.4 percent by 2029.17 Lithuania is boosting its defense spending to 5.38 percent of GDP in 2026.18 And all three nations are already well over the NATO benchmark of directing 20 percent of defense spending toward equipment, with Estonia at 25.8 percent, Latvia at 35.5 percent, and Lithuania at 45.8 percent.19

The Baltic nations also spend significant portions of their procurement budgets on US equipment. In October, Estonia increased its spending limit for US weapons from $500 million to $4.7 billion20 In addition to purchasing American-made capabilities for their own militaries, countries like Lithuania are contributing to the purchase of US equipment for Ukraine.21

Baltic nations are also investing heavily in defense infrastructure, much of which supports US forces deployed to the region. Estonia will spend around $576 million on military infrastructure between 2025 and 2028.22 Tallinn already spent $23.4 million to construct Camp Reedo, the first new base in the country since the nation regained independence, which opened in September 2024.23

Lithuania is spending over $1.2 billion on facilities to host allied troops, including training grounds and military mobility infrastructure, which should be completed in 2027.24 Latvia, for its part, expects to spend around $115 million on military infrastructure in 2025.25 The Baltic nations are also in the process of building out a joint Baltic defense line, which a recent analysis describes as:

A sophisticated network of trenches, bunkers, observation posts, anti-armor obstacles, and surveillance systems stretching along their borders with Russia and Belarus. The initiative is designed to delay and channel any potential Russian advance, to buy time for the deployment of reinforcements under Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty, and to impose operational costs on the attacker.26

Strengthening US-Baltic Defense Ties

The Baltic nations, which joined NATO in 2004, are model allies. These three states deployed thousands of troops alongside US forces in Afghanistan, losing a collective 14 soldiers. Three Latvian and two Estonian soldiers also lost their lives during US-led operations in Iraq. Thousands more served alongside US troops under trying circumstances.

But while military-to-military cooperation between the US and its Baltic allies grew through operations in Afghanistan and Iraq, the seeds of this partnership were sown much earlier. The National Guard State Partnership Program (SPP), which today boasts 106 partnerships with 115 nations,27 was a product of Washington’s desire to aid Eastern European nations as they reemerged from decades under the Soviet yoke. Retired Lieutenant General John B. Conaway, then chief of the National Guard Bureau, traveled to the Baltics in November 1992 as part of the first US military delegation to the region since the Second World War.28 He recalls thinking to himself on the return flight, “Why don’t we do a little partnership thing to help the Baltic emerging militaries get started, and help train them, and help them with equipment?”29 The following April, US states established the first SPP relationships with Baltic nations: Estonia partnered with Maryland, Latvia with Michigan, and Lithuania with Pennsylvania. The SPP has played a crucial role in building military, political, and fraternal ties between the US and its partners, particularly those in Eastern Europe.

Retired Army Lieutenant General H. Steven Blum, another former chief of the National Guard Bureau, underscored the important ambassadorial role American servicemembers played through the SPP. “They brought over American military values. Our partners saw it. You could feel it. You could touch it. And they saw it in all of our young men and women. Our guardsmen act as role models, and they counter all the propaganda.”30 The SPP undoubtedly aided the transformation of many nations in Eastern Europe, preparing them for eventual NATO accession.

Furthermore, the program is a two-way street. SPP relationships have been important in reinforcing the value of allies for a new generation of American soldiers. An American sergeant major recently underscored this point, saying, “When junior soldiers see senior leaders from two different countries working together, it makes them curious. They start to ask questions about language, culture, and cooperation. That’s how we build future leaders who understand the world.”31 Additionally, Americans can learn through the partnerships, such as when Lithuanian troops trained Pennsylvania National Guard members on how to use the M3 Carl Gustaf multirole anti-armor/antipersonnel weapon system in 2024.32

A History of US Deployments

In response to Russia’s illegal annexation of the Crimean Peninsula in 2014, the US began forward deploying troops permanently based in Europe on a rotational basis to Eastern European NATO allies. US troops based in Western Europe still take part in forward deployment exercises to Eastern Europe and across the alliance. For example, in the Defender 25 exercises this May, the 173rd Airborne Brigade, based in Vicenza, Italy, led an airborne assault exercise in Pabrade, Lithuania. The exercise also tested the brigade’s capability to deliver blood via drone.33

In addition to the temporary redistribution of forces permanently based in Europe under Operation Atlantic Resolve, the US began deploying domestically based forces (armor, aircraft, and a sustainment task force) on nine-month rotations to Europe. From there, they were forward deployed to eastern NATO allies.34

The US first sent rotational forces to the Baltic region in April 2014. About 150 troops from Italy went to each of the three Baltic states and Poland.35 The US maintained a company-size deployment (around 200 soldiers) in each of the Baltic states until 2017. These troops participated in exercises and worked to build interoperability with host nation forces.36 In 2017, NATO’s enhanced forward presence (EFP) battlegroups, which the alliance established at the 2016 Warsaw summit, became fully operational. The US continues to serve as the framework nation for the EFP battlegroup in Poland. The United Kingdom is the framework nation in Estonia, Canada in Latvia, and Germany in Lithuania.

In October 2019, the US returned to Lithuania. Five hundred US troops and 55 tanks and armored vehicles deployed for six months, a tour that culminated in exercises to secure the Suwalki Gap (a narrow corridor containing the Lithuania-Poland border between Belarus and Russia’s Kaliningrad). This deployment was the start of US forces’ persistent rotational presence in the nation. Even between 2017 and 2019, when the US had no regular presence, American special forces maintained a strong partnership with Lithuanian troops. This has grown into one of America’s most fruitful special forces partnerships within NATO.37

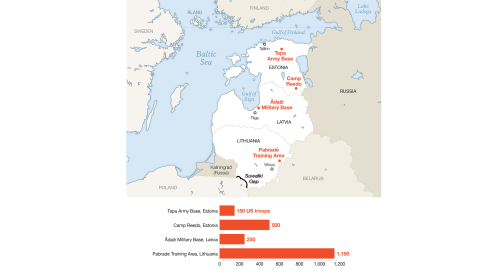

Map 1: US Rotational Presence in the Baltics

Source: Hudson Institute research.

Current Presence in the Baltic States

Today, the US deploys around 500 rotational troops from the US Army’s 5th Squadron, 7th Cavalry Regiment at the newly opened Camp Reedo, near Estonia’s border with Russia.38 In October 2025, the 6th Squadron, 9th Cavalry Regiment of the 1st Cavalry Division, based out of Fort Hood, Texas, deployed rotationally to Estonia with 14 Abrams tanks, marking the first US tank deployments to Estonia in a decade.39 Task Force Voit, a platoon-size High-Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS) training unit that had been deployed in Estonia since 2022, has transitioned to Lithuania to train local forces on the system in advance of the expected delivery of their HIMARS in 2027.40 The US also currently deploys around 150 troops rotationally in Tapa, Estonia, which is between Tallinn and the Russian border. On October 31, 2025, Estonian Defense Minister Hanno Pevkur stated that US forces would remain there and reiterated his commitment to expanding cooperation.41

There are currently about 250 US troops deployed in Latvia,42 and the US stations around 1,000 troops in Lithuania. In October 2025, the 1st Battalion, 12th Cavalry Regiment, and the 2nd Battalion, 82nd Field Artillery Regiment began their approximately nine-month rotational deployment to the nation.43 The Lithuanian ministry of defense has stated that these US deployments are “a strong deterrent in the current geopolitical security situation, while Lithuania exchanges experience and builds up ties as it trains.”44 In November, Lithuania announced that it would cover all costs associated with basing and maintaining a US presence in the country.45 The units rotating to Lithuania are part of the larger force rotated from the US under the auspices of Atlantic Resolve. In September 2025, the 3rd Armored Brigade Combat Team, 1st Cavalry Division, based in Fort Hood, Texas, deployed to Europe as the newest Atlantic Resolve rotation. The deployment consists of around 3,000 troops and 1,000 pieces of equipment.46

At the end of October, the US Department of War announced that the 2nd Infantry Brigade Combat Team of the 101st Airborne Division, based in Kentucky, would not be replaced when its rotation ended that month. The unit’s roughly 700 troops had deployed to Germany, Poland, and Romania on this tour.47 In announcing the decision, the DoW stated, “This is not an American withdrawal from Europe or a signal of lessened commitment to NATO and Article 5. Rather, this is a positive sign of increased European capability and responsibility. Our NATO allies are meeting President Trump’s call to take primary responsibility for the conventional defense of Europe. This force posture adjustment will not change the security environment in Europe.”48

Drawing Down the US Presence Would Undermine American Interests

The US presence in Europe is already at a historic low, as I recently wrote:

Today, less than 13 percent of permanently stationed forces in Europe are from the Navy, while the Air Force, which constitutes around 45 percent of US permanently stationed forces in Europe, currently deploys just three permanent fighter wings there (one each in Germany, Italy, and the UK). While the United States regularly deploys strategic bombers to Europe, it does not have any permanently based there. It bases only four Patriot missile batteries in all of Europe.49

There is little more that the US military could remove from Europe without seriously undermining NATO deterrence. To some planners, reducing or eliminating rotational forces may appear to be an easy way to reduce the number of US forces in Europe without needing to build new basing stateside or in another theater. Yet these rotational forces constitute a major part of the US presence in Eastern Europe and constitute America’s entire persistent presence in the Baltics. Rather than looking for quick ways to reduce its headcount in Europe, the DoW should seek to increase the deterrent value of the forces it has already committed to Eastern Europe by making their deployments permanent rather than rotational.50